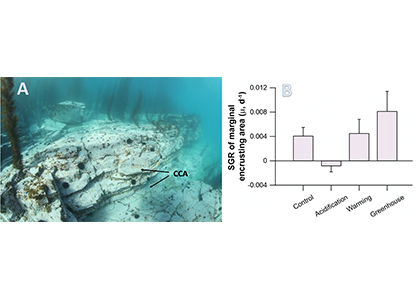

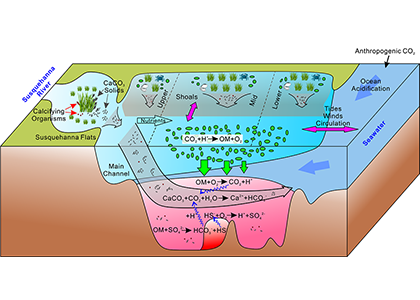

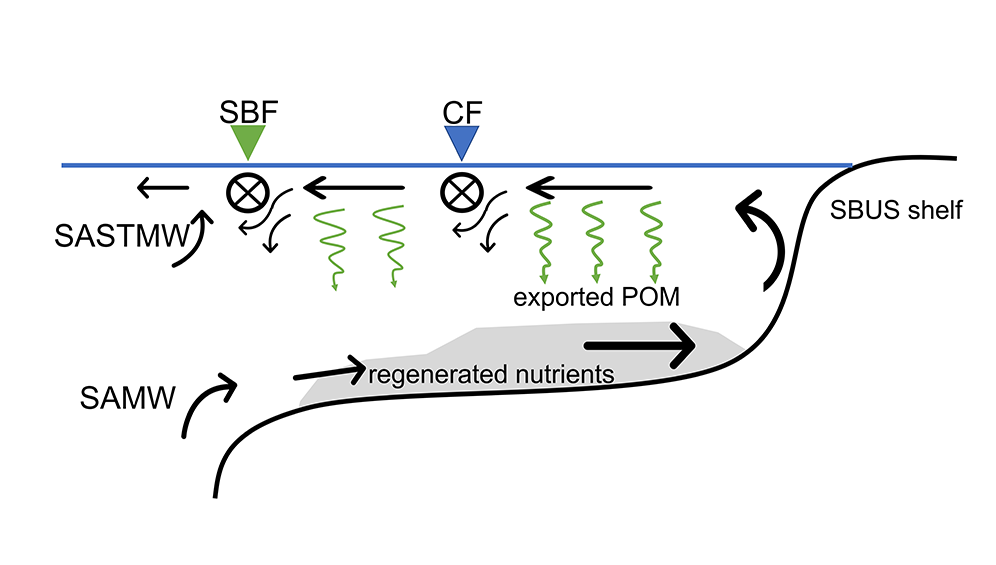

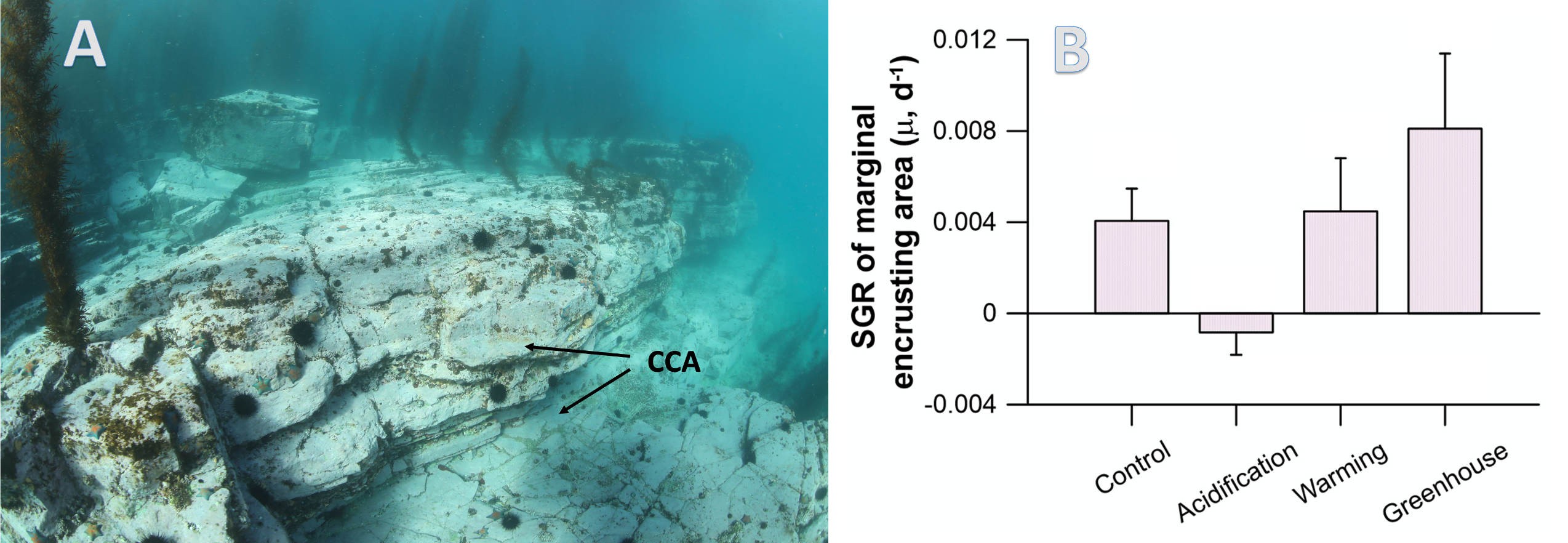

Seawater carbonate chemistry has been altered by dramatic increases in anthropogenic CO2 release and global temperatures, leading to significant changes in rocky shore habitats and the metabolism of most marine organisms. There has been recent interest in how these anthropogenic stresses affect crustose coralline algae (CCA) communities because CCA photosynthesis and calcification are directly influenced by seawater carbonate chemistry. CCA is a foundation species in temperate macroalgal communities, where species succession and rocky shore community structure are particularly susceptible to anthropogenic disturbance. In particular, the disappearance of turf and foliose macroalgae caused by climate change and herbivore pressure results in the dominance of CCA (Figure 1a).

Figure 1: (a) Examples of crustose coralline algae (CCA)-dominated seaweed bed in the East Sea of Korea showing barren ground dominated by CCA (bright white and pink color on the rock; see arrows) on a rocky subtidal zone grazed by sea urchins. (b) Specific growth rate of marginal encrusting area under future climate conditions.

In a recent study published in Marine Pollution Bulletin, the authors conducted a mesocosm experiment to investigate the sensitivity of temperate CCA Chamberlainium sp. to future climate stressors, as simulated by three experimental treatments: 1) Acidification: doubled CO2; 2) Warming: +5ºC; and 3) Greenhouse: doubled CO2 and +5ºC. After a 47-day acclimation period, when compared with present-day (control: 490 μatm and 20ºC) conditions, the Acidification treatment showed decreased photosynthesis rates of Chamberlainium sp, whereas the Warming treatment showed increased photosynthesis. The Acidification treatment also showed reduced encrusting growth rates relative to the Control, but when acidification was combined with warming in the Greenhouse treatment, encrusting growth rates increased substantially (Figure 1b). Taken together, these results suggest that the negative ecophysiological responses of Chamberlainium sp to acidification are ameliorated by elevated temperatures in a greenhouse world. In other words, if the foliose macroalgal community responses negatively in the greenhouse environment, the dominance of CCA will increase further, and the biodiversity of the algae community will be reduced.

Authors:

Ju-Hyoung Kim (Faculty of Marine Applied Biosciences, Kunsan National University)

Il-Nam Kim (Department of Marine Science, Incheon National University)