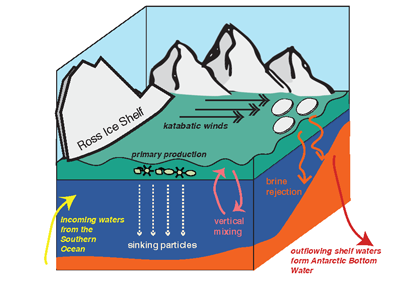

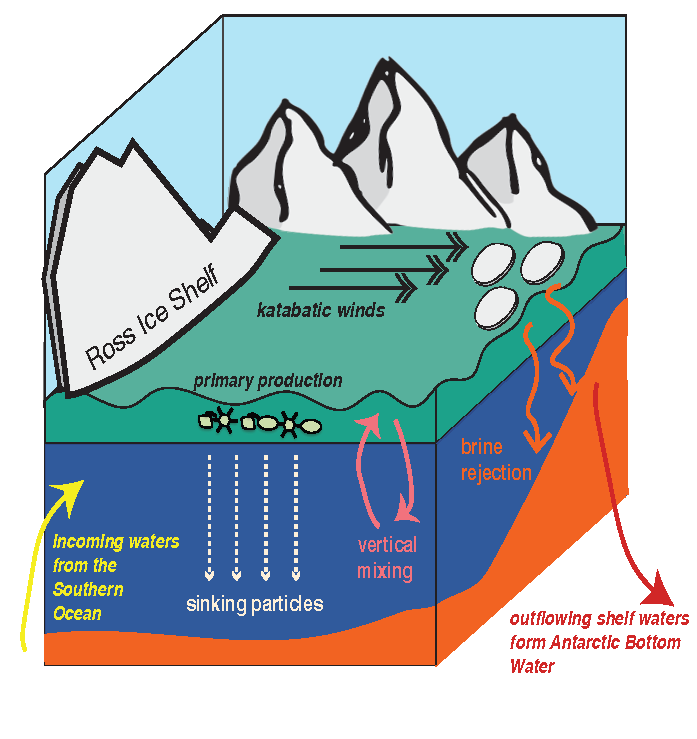

Barely visible to the naked eye, gelatinous zooplankton play important roles in marine food webs. Cnidaria, Ctenophora, and Urochordata are omnipresent and provide important food sources for many more highly developed marine organisms. These small, nearly transparent organisms also transport large quantities of “jelly-carbon” from the upper ocean to depth. A recent study in Global Biogeochemical Cycles focused on quantifying the gelatinous zooplankton contribution to the ocean carbon cycle.

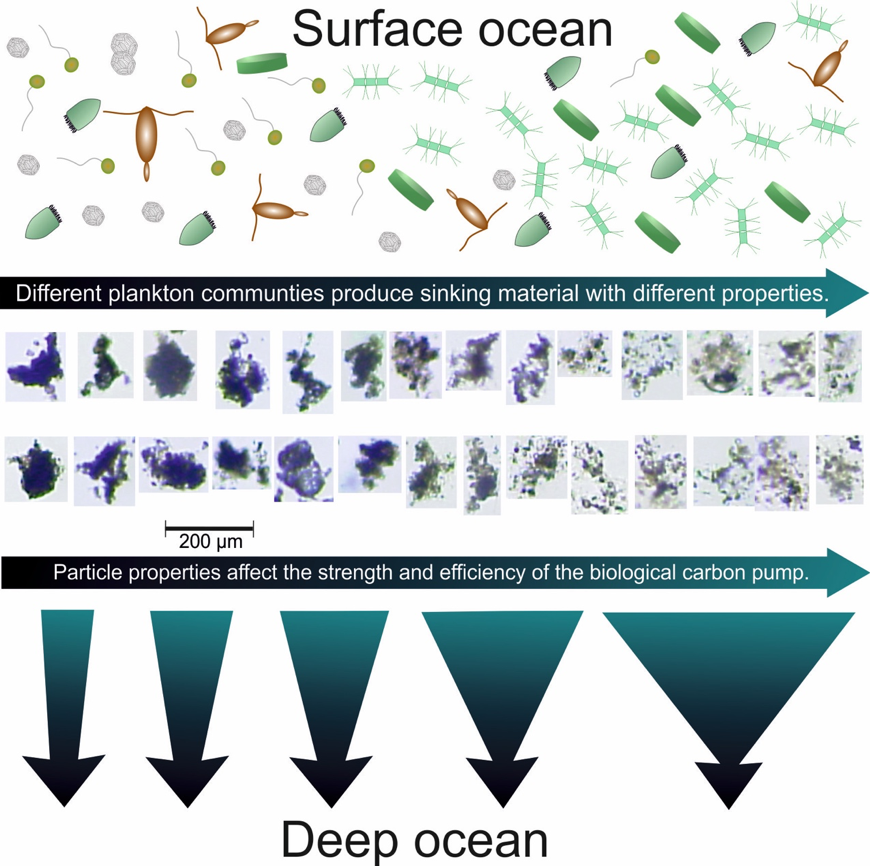

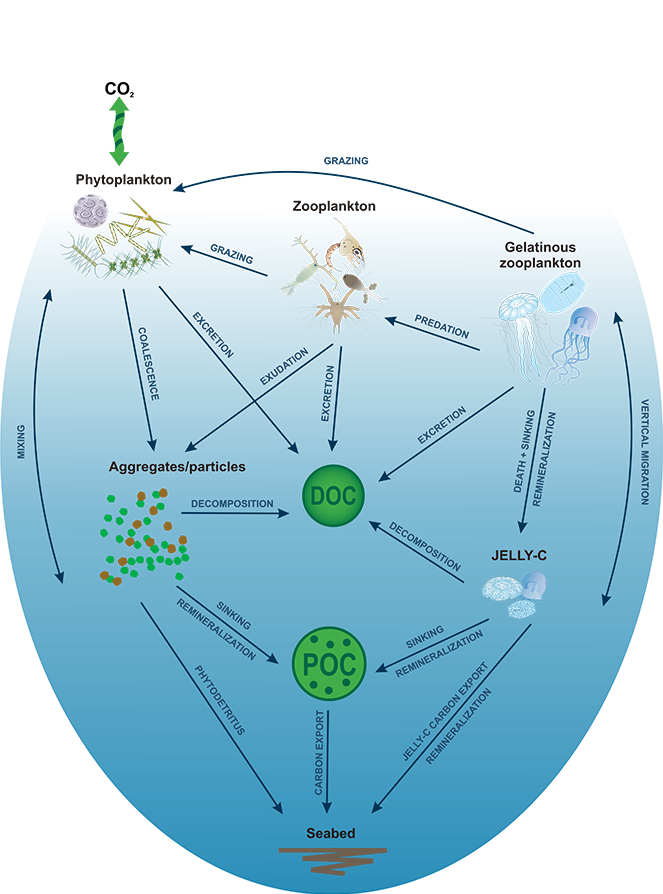

Figure 1. Processes and pathways or gelatinous carbon transfer to the deep ocean.

Using >90,000 data points (1934 to 2011) from the Jellyfish Database Initiative (JeDI), the authors compiled global estimates of jellyfish biomass, production, vertical migration, and jelly carbon transfer efficiency. Despite their small biomass relative to the total mass of organisms living in the upper ocean, their rapid, highly efficient sinking makes them a globally significant source of organic carbon for deep-ocean ecosystems, with 43-48% of their upper ocean production reaching 2000 m, which translates into 0.016 Pg C yr-1.

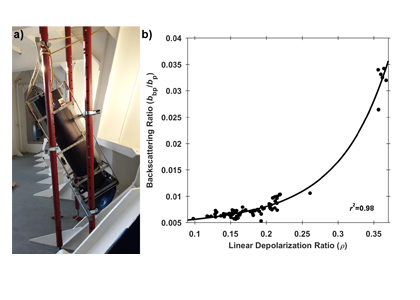

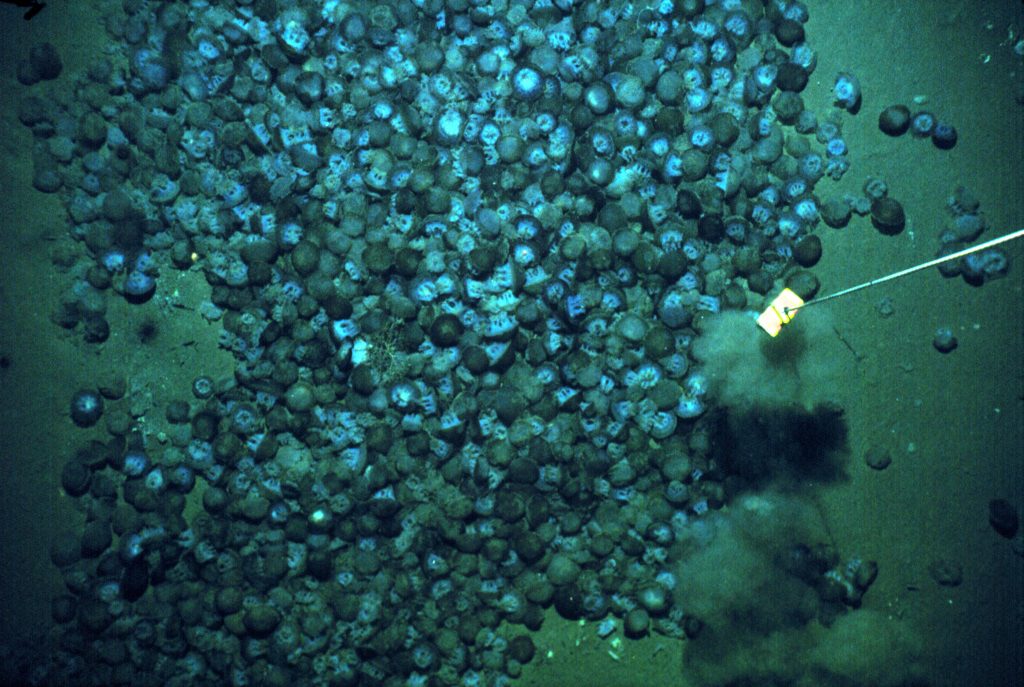

Figure 2. Mass deposition event of jellyfish at 3500 m in the Arabian Sea (Billett et al. 2006).

Sediment trap data have suggested that carbon transport associated with large, episodic gelatinous blooms in localized open ocean and continental shelf regions could often exceed phytodetrital sources, in particular instances. These mass deposition events and their contributions to deep carbon export must be taken into account in models to better characterize marine ecosystems and reduce uncertainties in our understanding of the ocean’s role in the global carbon cycle.

Links:

Jellyfish Database Initiative http://jedi.nceas.ucsb.edu, http://jedi.nceas.ucsb.edu-dmo.org/dataset/526852 )

Authors:

Mario Lebrato (Christian‐Albrechts‐University Kiel and Bazaruto Center for Scientific Studies, Mozambique)

Markus Pahlow (GEOMAR)

Jessica R. Frost (South Florida Water Management District)

Marie Küter (Christian‐Albrechts‐University Kiel)

Pedro de Jesus Mendes (Marine and Environmental Scientific and Technological Solutions, Germany)

Juan‐Carlos Molinero (GEOMAR)

Andreas Oschlies (GEOMAR)