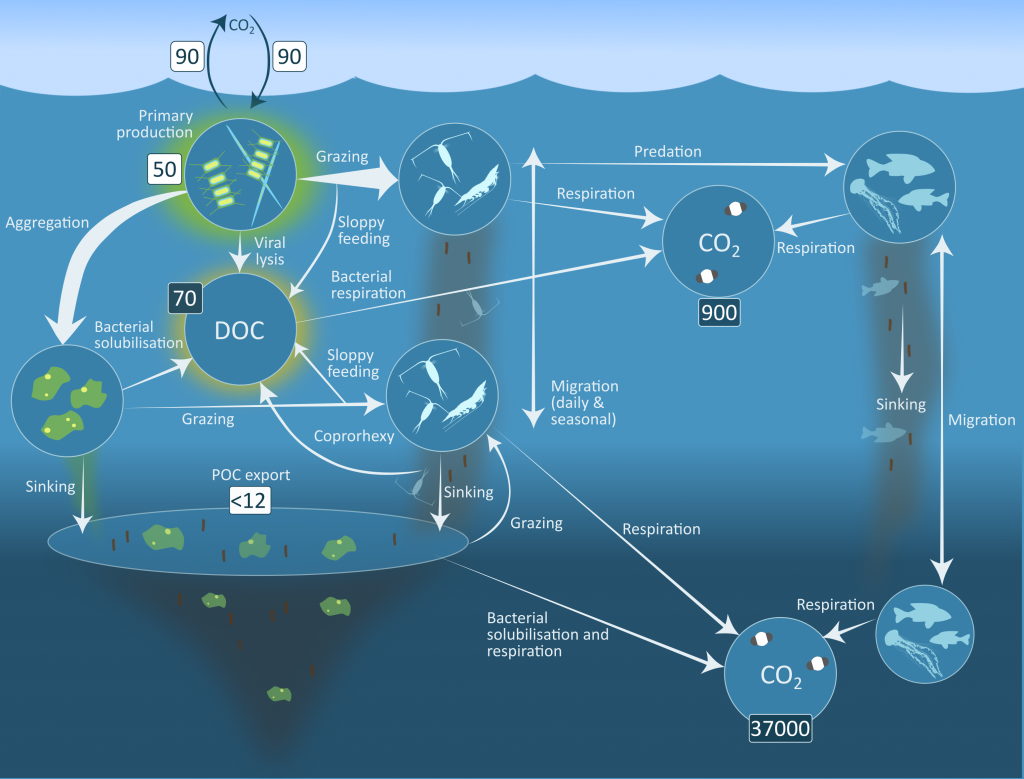

Despite the importance of particulate organic carbon (POC) export on carbon sequestration and marine ecology, there have been few multi-decade studies in the world’s oceans. A new analysis published in Nature analyzed two decades of POC export data in the West Antarctic Peninsula and found that export oscillates on a 5-year cycle.

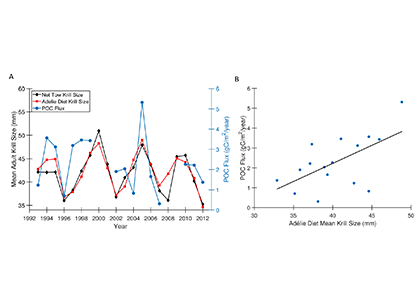

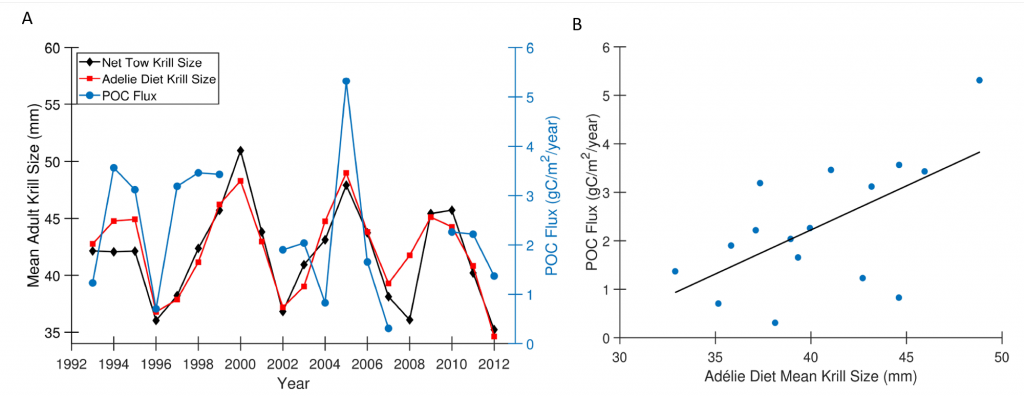

Figure caption: A) Particulate organic carbon (POC) export oscillates on a 5-year timescale in sync with the oscillation in the body size of the krill Euphausia superba on the West Antarctic Peninsula. B) POC export is significantly correlated with krill body size (p = 0.01).

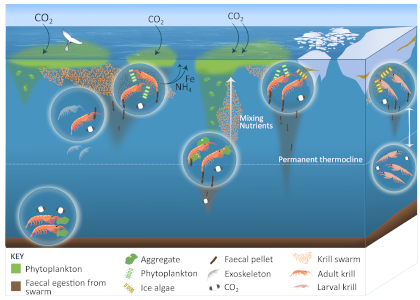

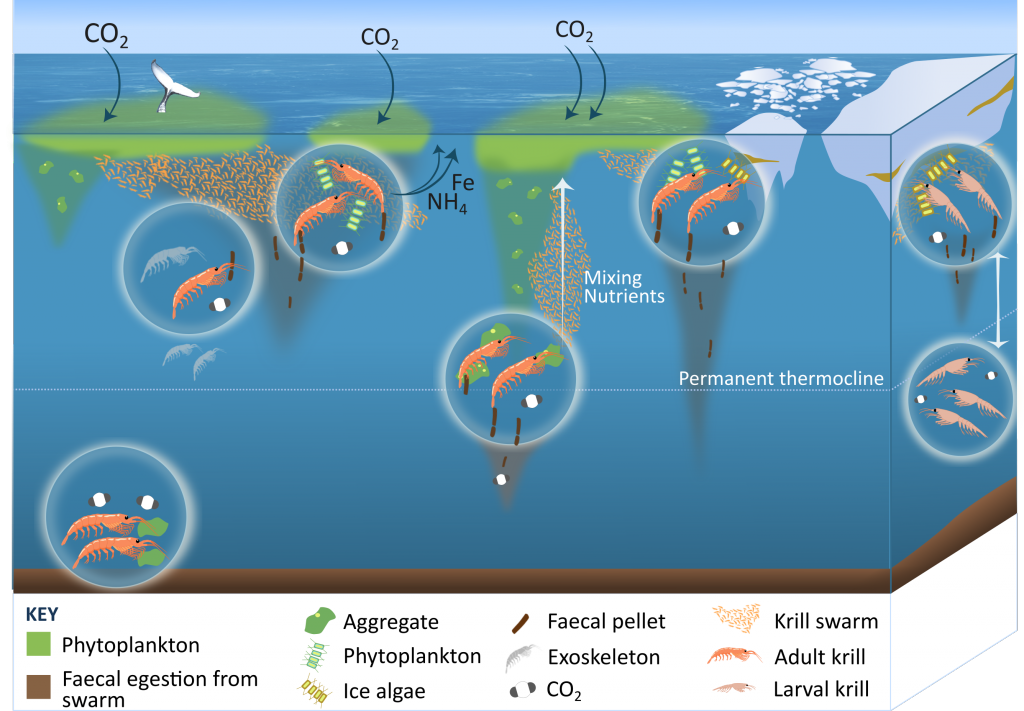

Using a unique combination of krill data from penguin diet samples and net tows over two decades, Trinh et al. found that the cycle of POC export is intimately tied to the Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) life cycle, as the bulk of the POC in their sediment traps was krill fecal pellets. Surprisingly, more krill did not lead to more POC export. Instead, when the krill population size was smaller but dominated by larger, older adults, POC export increased.

E. superba is the longest-lived (5-6 years) and largest krill species. They exhibit continuous annual growth throughout their life cycle. After about five years a krill population reaches its end stage and the population size is at a minimum. This end-stage population is composed of large, 50-60 mm long individuals that produce large, fast-sinking fecal pellets, leading to increased POC export. Increasing temperatures and deterioration of sea ice cover during the winter season due to climate change will likely impact the recruitment of new cohorts of krill and their success in replenishing aging populations. It is unclear how changes in the krill population and life cycle will impact long-term carbon sequestration on the West Antarctic Peninsula and nutrients exported to the benthic ecosystem

Authors:

Rebecca Trinh (Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University)

Hugh Ducklow (Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University)

Deborah Steinberg (Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary)

William Fraser (Polar Oceans Research Group)