When we collect seawater in any point of the ocean, we are collecting a mix of water masses from different origin that traveled until there keeping their salinity and temperature properties. The Atlantic Ocean is likely the most complex basin in term of water masses containing more than 15 in its depths. Some of them were “born” in the North Atlantic Ocean, others in the Southern Ocean, even in the Mediterranean Sea! And when we collect a seawater sample we can know which water masses are there, where they come from, what happened to each of them during their journey to us, what story can they tell us.

The variation of any non-conservative property (such as dissolved organic carbon or nutrients) in the deep open ocean depends on the mixing of those water masses and on the biogeochemical processes affecting it (such as heterotrophic respiration). But the effect of the water mass mixing is usually very high, so in order to study the biogeochemical processes, it is necessary to remove that effect.

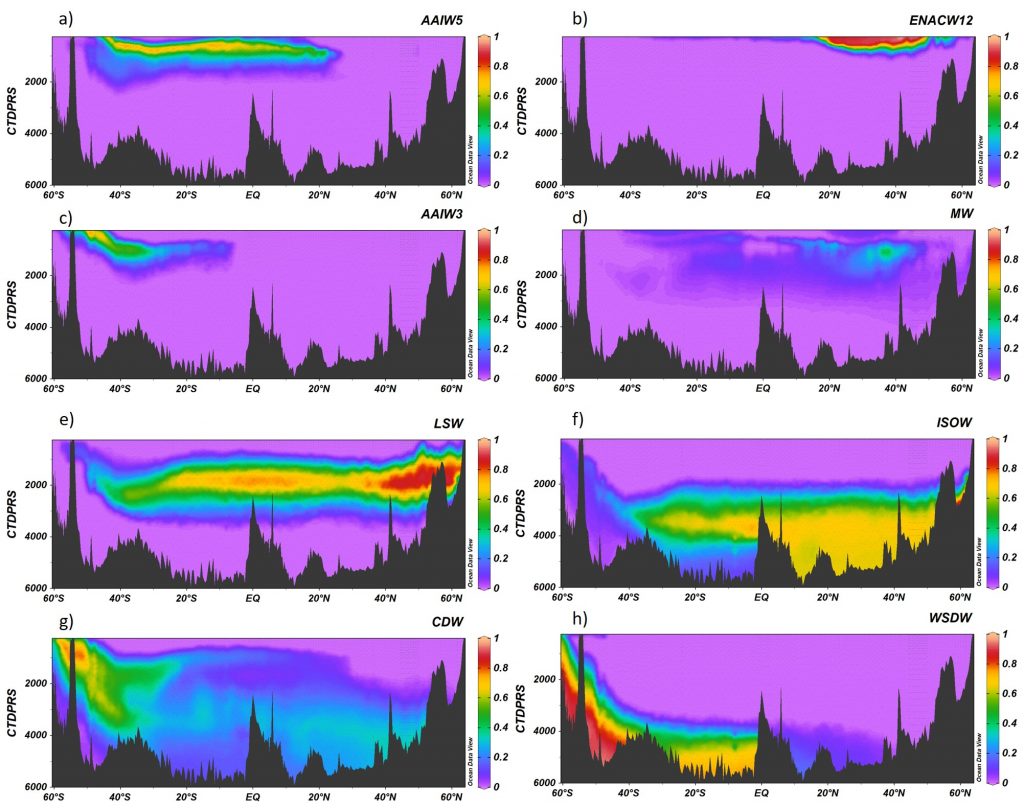

On the other hand, estimating the contribution of the water masses composing a sample is useful to trace the distribution of each water mass identifying the depth of maximum water mass contribution or the depth-range where the water mass is dominant contributing > 50%. Ocean biogeochemists and microbiologists can get more out of their data estimating the impact of water mass mixing on the variability of any chemical (e.g. inorganic nutrients and dissolved organic carbon) or biological (e.g. prokaryotic heterotrophic abundance and production) property.

Knowing the contribution of each water mass to each sample was not an easy task and required expertise on the origin, circulation and mixing patterns of the water masses present in the study area. This could be even harder in very complex oceanic basin such as the deep Atlantic Ocean. The most commonly used methodology is the Optimum Multi-Parameter (OMP) analysis that was first applied by Tomczak in 1981. However, this methodology is time consuming and requires availability of a large set of quality-controlled chemical variables (e.g. nutrients, oxygen,..) together with a deep knowledge of the oceanography of the studied area. Those chemical variables are not always available or do not have the required quality by contrast to potential temperature and salinity that are high standard core variables in any cruise or database. In a recent research article, we applied multi-regression machine learning models to solve ocean water mass mixing. The models tested were trained using the solutions from OMP analyses previously applied to samples from cruises in the Atlantic Ocean. Extremely Randomized Trees algorithm yielded the highest score (R2 = 0.9931; mse = 0.000227). The model allows solving the mixing of water masses in the Atlantic Ocean using potential temperature, salinity, latitude, longitude and depth. Potential temperature and salinity are the most commonly collected and curated variables in oceanography both from oceanographic cruises and autonomous vehicles (e.g. ARGO) avoiding the use of less commonly measured chemical variables which also require longer and time-consuming analyses of both the water samples and the data.

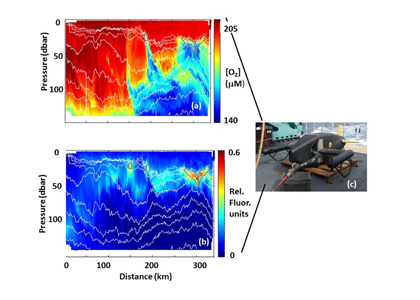

Figure 1. A16 section for the contribution of the water masses (A) AAIW5, (B) ENACW12, (C) AAIW3, (D) MW, (E) LSW, (F) ISOW, (G) CDW and (H) WSDW obtained with the Extremely Randomized Trees algorithm. Ocean Data View software (Schlitzer, 2015).

We also provide the code with instructions where any user can easily introduce the required variables (latitude, longitude, depth, temperature and salinity) of the chosen Atlantic samples and obtain the water mass proportion of each one in a fast and easy way. Actually, it would allow the user to obtain this information in real time during a cruise.

New research using other methods like OMP and its variants can be incorporated to the existing model increasing its accuracy and prediction capacity. Help us to improve the model and increase its spatial resolution!

Ocean biogeochemists and microbiologists can benefit from this tool even if they do not have a deep knowledge of the oceanography of the studied area. Identifying the water masses composition of a sample has never been so easy!

Author

Cristina Romera-Castillo (Instituto de Ciencias del Mar-CSIC, Barcelona, Spain)

Twitter: @crisrcas