Mixotrophs (or mixoplankton) are now accepted as a third group of plankton alongside phytoplankton and zooplankton. Our knowledge of mixotrophs lags far behind that of the other two groups. We currently have only a limited understanding of mixotrophs’ biogeographical distribution across ocean basins, and what environmental factors are associated with their distribution.

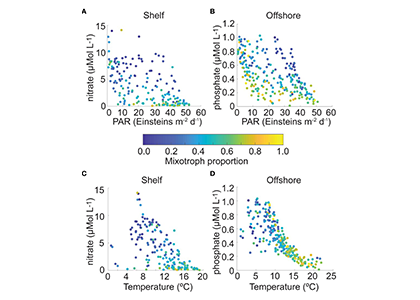

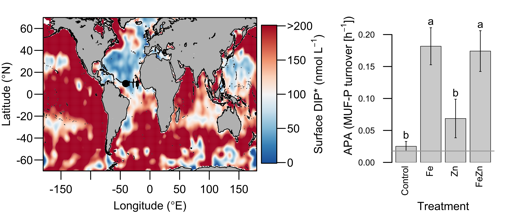

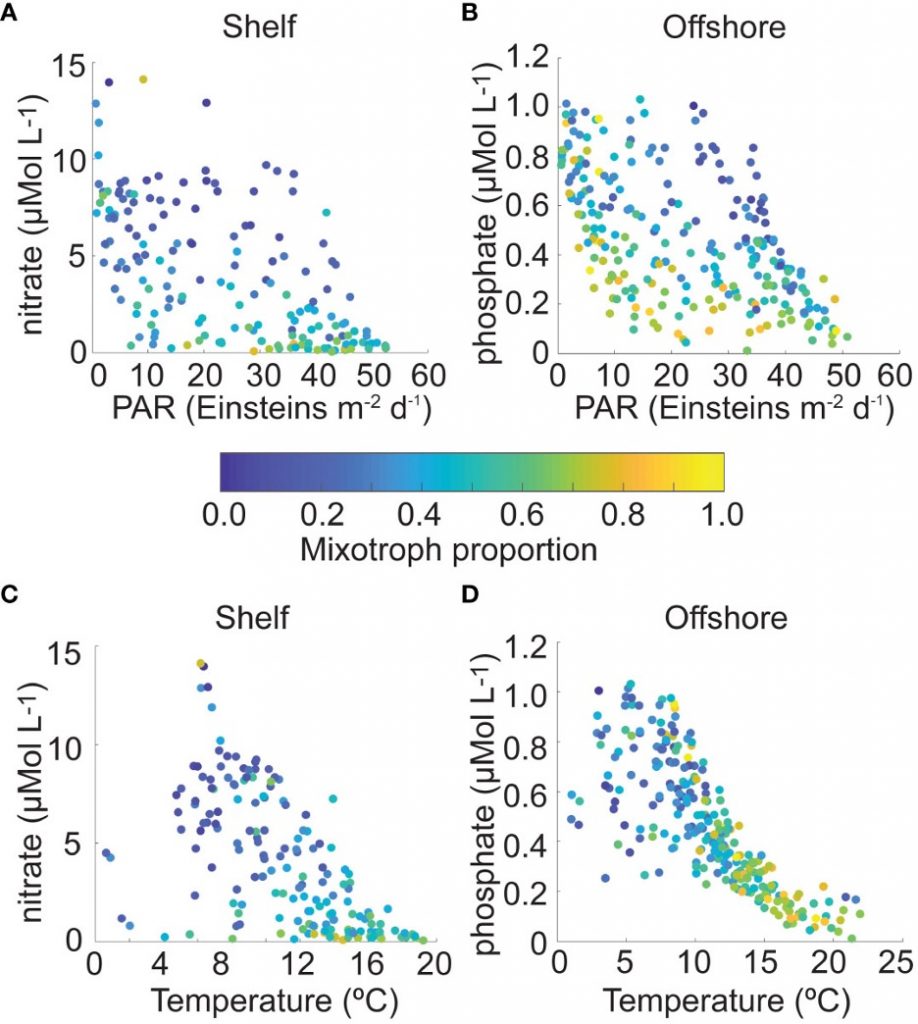

The authors of a study recently published in Frontiers in Marine Science reviewed nearly 230,000 individual microplankton samples collected by the North Atlantic Continuous Plankton Recorder program between 1958 and 2015 and calculated the proportion of organisms that are considered mixotrophs in each sample. They classified protist species in the dataset as phytoplankton, mixotrophs, or microzooplankton (heterotrophs), based on existing literature. Taken together across seasonsin shelf waters (depth ≤ 300m), mixotrophs comprise a greater proportion of the microplankton community when nitrate is high and photosynthetically available radiation (PAR) is low (e.g. during the late fall and winter), or when nitrate is low and PAR is moderate to high (e.g. during the summer and early fall). When both nitrate and PAR are high, mixotrophs comprise less of the community compared to phytoplankton. The same pattern was found in offshore waters (depth > 300m), but the key macronutrient was phosphate rather than nitrate. The annual average proportion of mixotrophs in microplankton samples compared to phytoplankton has increased since 1958 in the offshore portion of the study region, with a notable changepoint in 1993; this increasing trend is strongest in the winter season.

This paper is useful for aquatic ecologists who want to integrate mixotrophic plankton into their understanding of marine food webs and biogeochemical cycles. Understanding mixotroph temporal and spatial distributions, as well as the environmental conditions under which they flourish, is imperative to understanding their impact on trophic transfer and biogeochemical cycling.

Authors

Karen Stamieszkin (Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences)

Nicole Millette (Virginia Institute of Marine Science)

Jessica Luo (NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory)

Elizabeth Follett (University of Liverpool)

Nick Record (Bigelow Laboratory of Ocean Science)

David Johns (Marine Biological Association)

Backstory

This work and the collaboration that made it possible was catalyzed by the Eco-DAS XII symposium, attended by Karen Stamieszkin, Nicole Millette, Jessica Luo, and Elizabeth Follett in 2016. Nicole had an idea for an analysis but lacked collaborators, just as she was ready to give up on it, Karen, Jessica, and Elizabeth expressed interest in the project. Karen, Jessica, and Elizabeth each brought a unique perspective that helped make Nicole’s original idea more practical and ensured that the analysis would come to life.

The collaboration that began with this paper lead to the OCB Mixotrophs & Mixotrophy Working Group led by Karen, Jessica, and Nicole, and a successful grant proposal to study mixotrophy awarded to Nicole and Karen by NSF’s Biological Oceanography program. This story shows the importance and power of programs that connect researchers across disciplines, especially in the early stages of their careers.