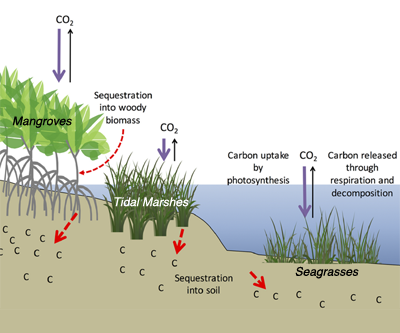

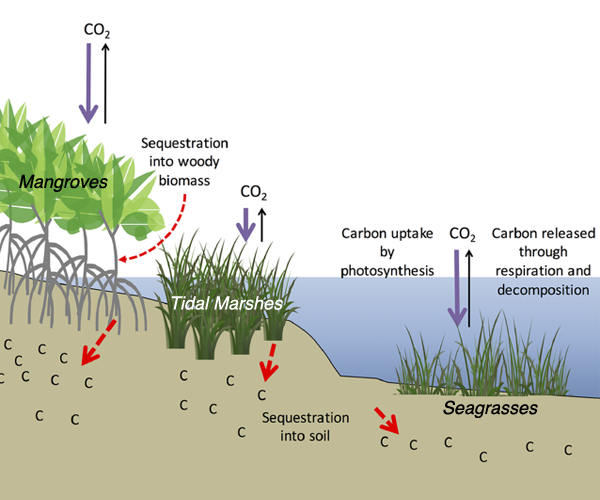

Coastal management actions aimed at protecting or restoring seagrass meadows are often assumed to have the collateral benefit of removing large amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to combat climate change. Be aware, however: not all seagrass meadows are alike. Under certain conditions, some release more carbon dioxide than they absorb and are net carbon sources to the atmosphere. This is now shown in a new study by an international team of researchers, published in the scientific journal Science Advances. This study combined direct eddy covariance measurements of air-water gas exchange with geochemical approaches to build a comprehensive carbon budget for a tropical seagrass meadow in south Florida. The process of ecosystem calcification released far more CO2 to the atmosphere than was buried in sediments as “Blue Carbon.” This study questions the reliability of Blue Carbon approaches towards net CO2 sequestration in tropical waters. But still unclear is how applicable these results are to the global scale, and what fraction of tropical seagrass meadows are net sources, rather than sinks, of CO2 to the atmosphere.

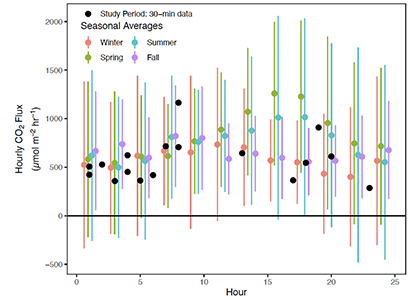

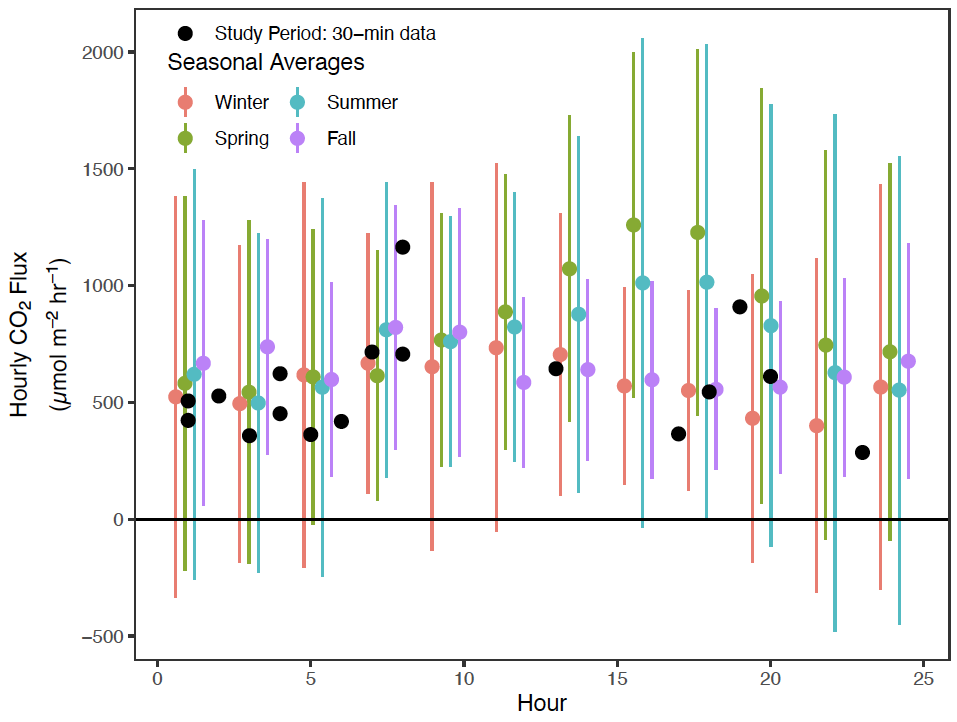

Figure 1 : Diel trend in CO2 flux presented as discrete 30-min measurements during the study period (black circles) and annual mean fluxes for the year surrounding the study period, binned in 2-hour intervals [colored circles (x ± SD)].

Authors

Bryce R. Van Dam (Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon)

Mary A. Zeller (Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research)

Christian Lopes (Florida International University)

Ashley R. Smyth (University of Florida)

Michael E. Böttcher (Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research)

Christopher L. Osburn (North Carolina State University)

Tristan Zimmerman (Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon)

Daniel Pröfrock (Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon)

James W. Fourqurean (Florida International University)

Helmuth Thomas (Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon)