Carbon dioxide removal (CDR) is “unavoidable” in efforts to limit end-of-century warming to below 1.5 °C. This is because some greenhouse gas emissions sources—non-CO2 from agriculture, and CO2 from shipping, aviation, and industrial processes—will be difficult to avoid, requiring CDR to offset their climate impacts. Policymakers are interested in a wide variety of ways to draw down CO2 from the atmosphere, but to date, the modeling scenarios that inform international climate policies have mostly used biomass energy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) as a proxy for all CDR. It is critical to understand the potential of a full suite of CDR technologies, to understand their interactions with energy-water-land systems and to begin preparing for these impacts.

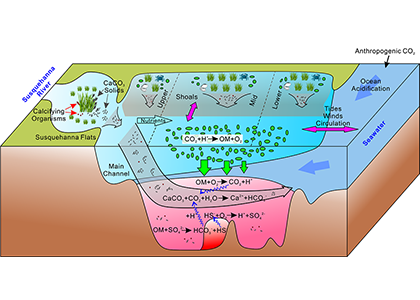

Figure caption: Each of the six carbon dioxide removal approaches identified in recent U.S. legislation and modeled for this study could bring unique benefits and tradeoffs to the energy-water-land system. This image depicts afforestation, direct ocean capture, direct air capture, biochar, enhanced weathering, and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage in clockwise order. Floating carbon dioxide molecules hover above the landscape (image credit: Nathan Johnson, PNNL).

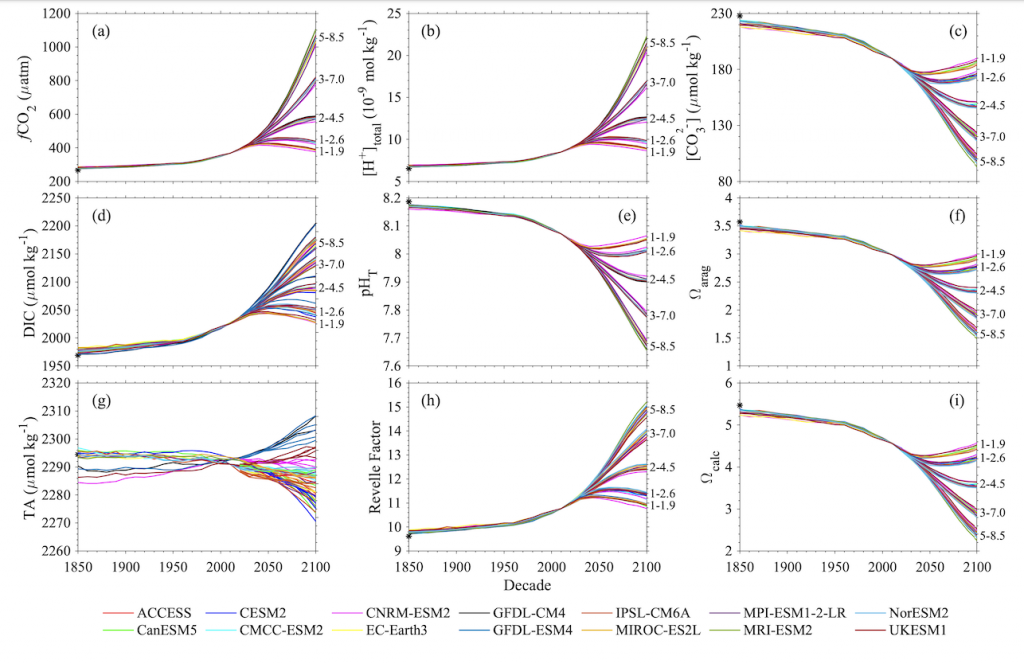

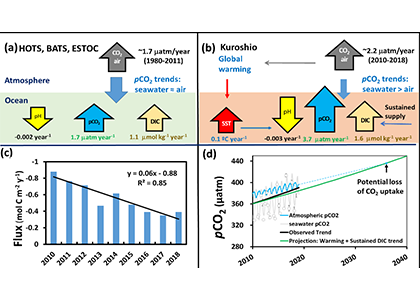

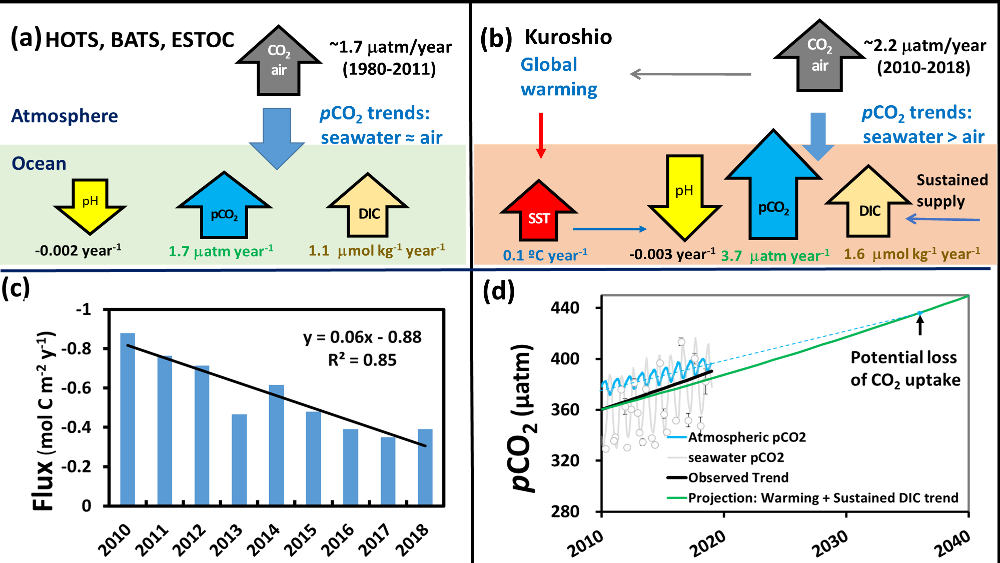

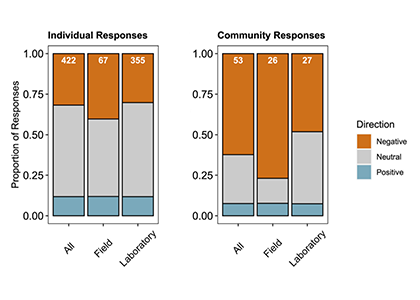

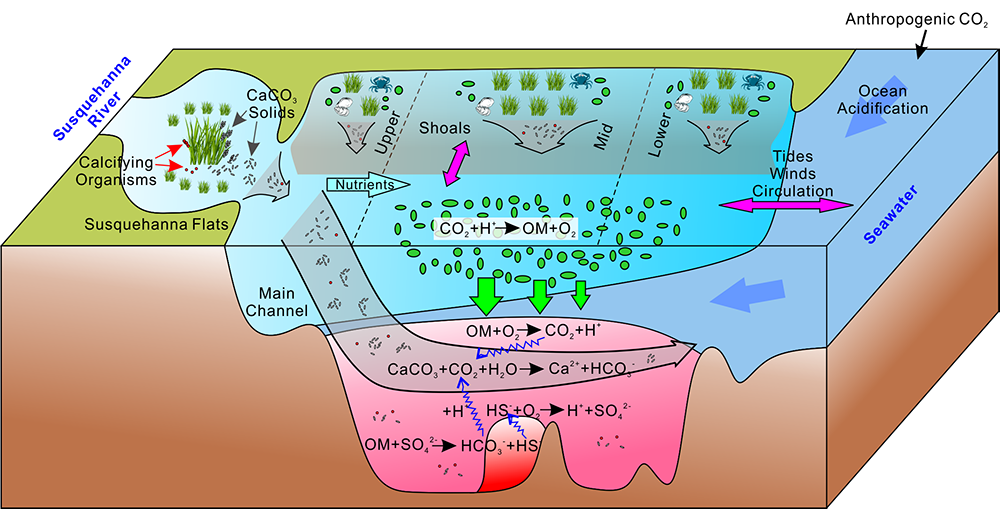

A recent study published in the journal Nature Climate Change was the first to model six major CDR pathways in an integrated assessment model. The modeled pathways range from bioenergy with carbon storage and afforestation (already represented by most models), also direct air capture, biochar and crushed basalt spreading on global croplands, and electrochemical stripping of CO2 from seawater aka direct ocean capture. The removal potential contributed by each of the six pathways varies widely across different regions of the world. Direct ocean capture showed the smallest removal potential but has important potential synergies with water desalination. This method could help arid regions such as the Middle East meet their water needs in a warming world. Enhanced weathering has much larger (GtCO2-yr-1) removal potential and could potentially help ameliorate ocean acidification. Overall, similar total amounts of CO2 are removed compared to other modeling scenarios, but broader set of technologies lessens the risk that any one of them would become politically or environmentally untenable.

Authors:

Jay Fuhrman (Joint Global Change Research Institute)

Candelaria Bergero (Joint Global Change Research Institute)

Maridee Weber (Joint Global Change Research Institute)

Seth Monteith (ClimateWorks Foundation)

Frances M. Wang (ClimateWorks Foundation)

Andres F. Clarens (University of Virginia)

Scott C. Doney (University of Virginia)

William Shobe (University of Virginia)

Haewon McJeon (Joint Global Change Research Institute )

Twitter: @pnnlab @climateworks @uva