Ocean acidification and rising temperatures have led to concerns about how calcifying organisms foundational to marine ecosystems, will be affected in the near future. We often look to analogous abrupt climate change events in Earth’s geologic past to inform our predictions of these future communities. The Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum (PETM) is an apt analog for modern climate change. The PETM was a global warming and ocean acidification event driven by geologically abrupt changes to the global carbon cycle approximately 56 million years ago. Much of what we know about the PETM is from the study of deep sea sedimentary records and the microfossils within them. However, these records can experience intense sediment mixing—from bottom water currents and burrowing by organisms living along the seafloor—which can blur or distort the primary climate and ecological signals in these paleorecords.

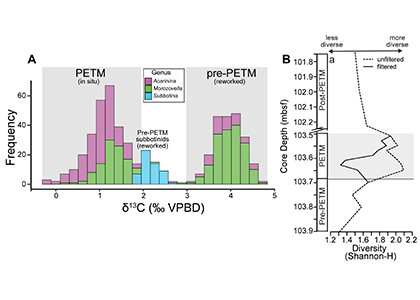

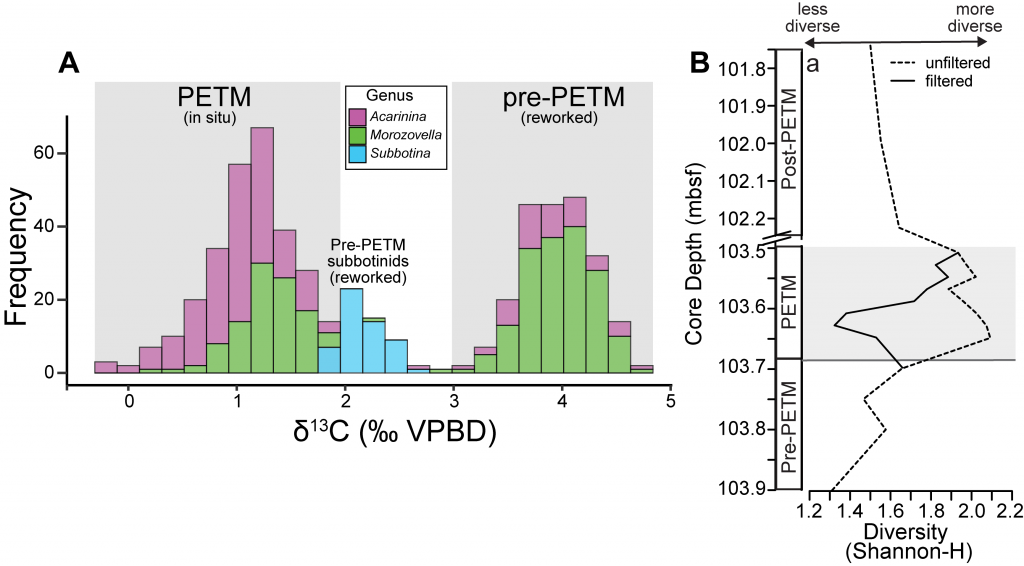

Figure 1. A) Frequency distribution of single-shell stable carbon isotope (δ13C) values for planktic foraminiferal shells from a deep sea sedimentary PETM record from the equatorial Pacific (n = 548). Note that 50% of shells measured record distinctly PETM values, while 49.5% record distinctly pre-PETM values. B) Comparison of diversity metric (Shannon-H) between the isotopically filtered (i.e., unmixed) and unfiltered (i.e., mixed) planktic foraminiferal assemblages.

A recent study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences used geochemical signatures measured from individual microfossil shells of planktic foraminifera (surface-dwelling marine calcareous zooplankton) to deconvolve the effects of sediment mixing on a deep sea PETM record from the equatorial Pacific. Use of this “isotopic filtering” (unmixing) method revealed that nearly 50% of shells in the PETM interval were reworked contaminants that lived before the global warming event (Figure 1A). The identification and removal of these older shells from fossil census counts drastically changed interpretations of how these organisms responded to the PETM. Prior interpretations assumed that planktic foraminiferal communities living near the equator diversified during the PETM. However, by deconvolving the effects of sediment mixing on the same equatorial deep sea record, researchers found that these communities actually suffered an abrupt decrease in diversity at the onset of the PETM (Figure 1B). This decrease is likely due to several taxa migrating towards the poles to escape the extreme heat of the tropics and lower oxygen conditions found at deeper water depths (i.e., thermocline) during the PETM. Additionally, some taxa may have undergone morphological changes, signaling reduced calcification, in response to extreme acidifying conditions. Today, anthropogenic carbon emission rates are ~10 times faster than the carbon cycling perturbation that triggered the PETM. Although planktic foraminifera and other key zooplankton survived the PETM, these communities suffered at the hands of extreme sea surface temperatures and acidifying waters, and may not be able to cope the rate of environmental changes in our ocean over the coming centuries.

Authors:

Brittany N. Hupp (University of Wisconsin-Madison)

D. Clay Kelly (University of Wisconsin-Madison)

John W. Williams (University of Wisconsin-Madison)