Biological impacts of ocean acidification have been the subject of intense research for more than a decade. While it is known that more acidic seawater will create difficulties for calcifying organisms (e.g. corals or coccolithophores), diatoms have so far been considered to be resilient against, or even benefit from, ocean acidification. But an overlooked biogeochemical feedback mechanism has revealed that diatoms are also under threat from ocean acidification.

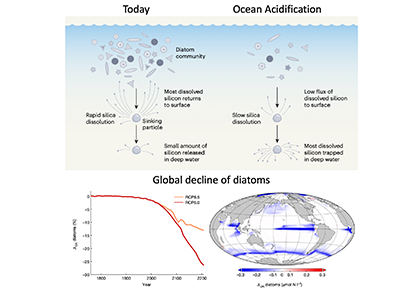

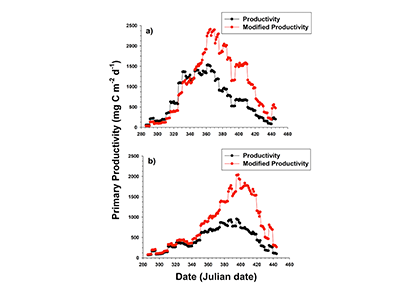

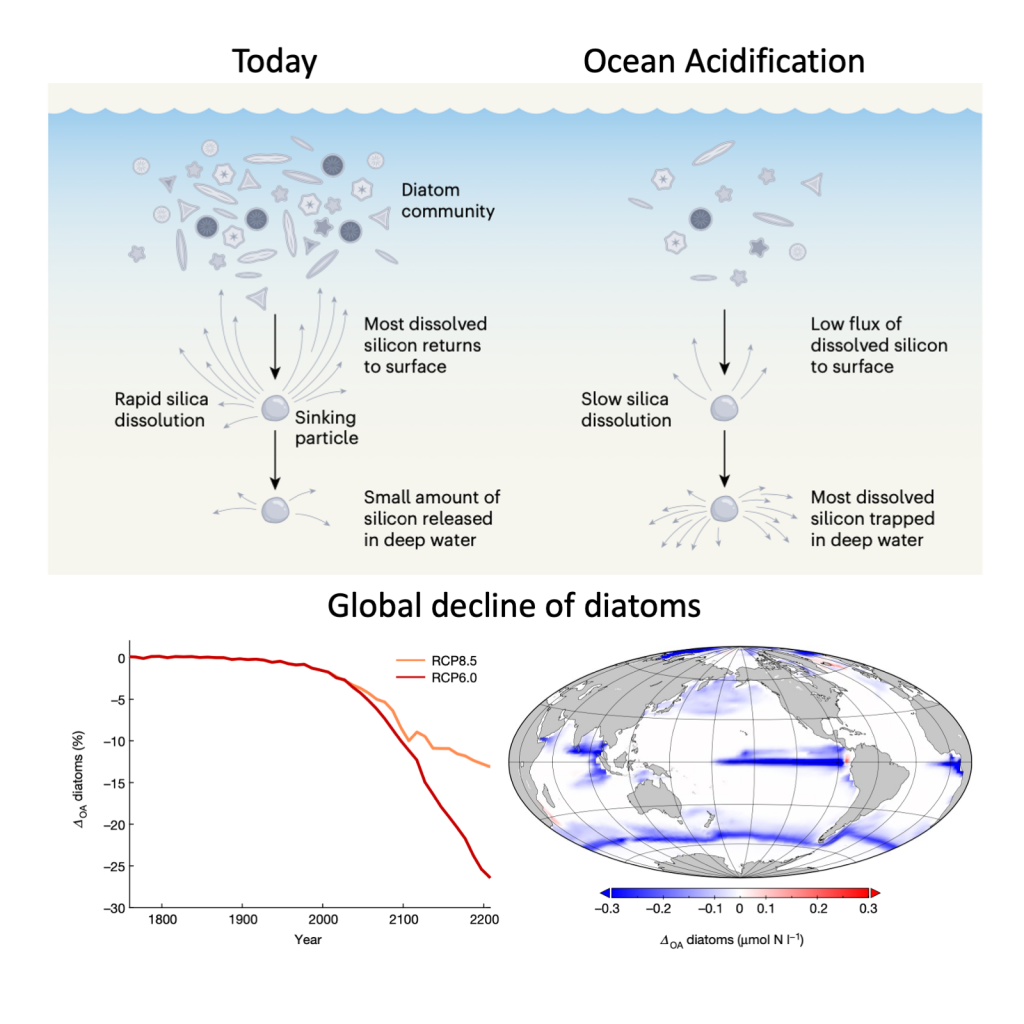

Figure 1: Slower solubility of diatom shells in acidified oceans leads to global diatom decline. Diatoms build silica shells and produce organic carbon at the ocean surface. Today, much of the silica dissolves relatively quickly as the particles consisting of dead diatoms sink (e.g. after blooms). The resulting dissolved silicon is returned to the surface by upwelling waters, where it supports the growth of more diatoms. Under ocean acidification, the silica in sinking particles will dissolve slower, thereby reducing the return flux of dissolved silicon to the ocean surface as much of the marine silicon budget will become trapped in deep water. The result is a substantial global decrease in diatom biomass. (Figure source: Nature, Vol. 605, No. 7911, 26 May 2022, DOI: 10.1038/d41586-022-01365-z and 10.1038/s41586-022-04687-0)

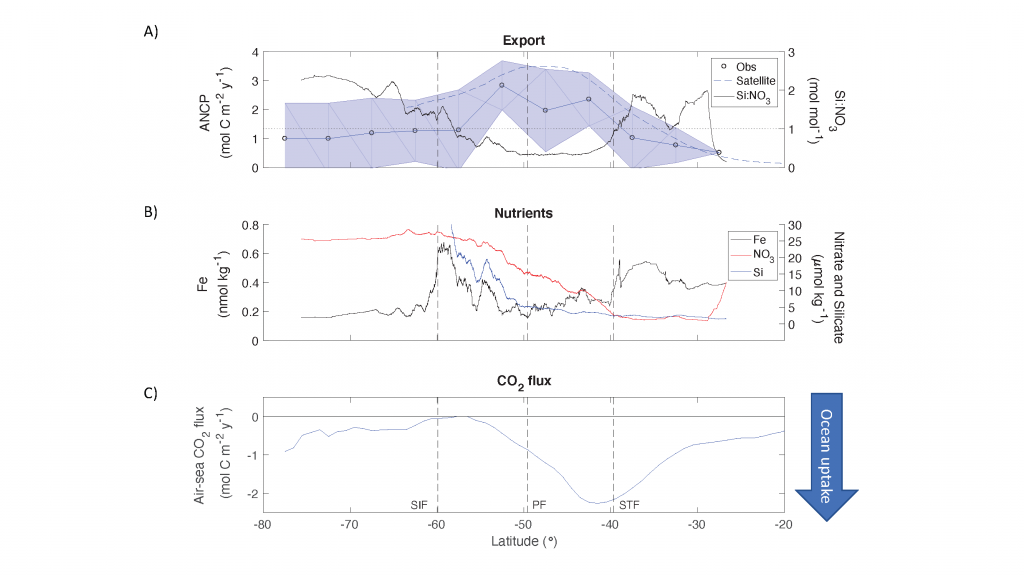

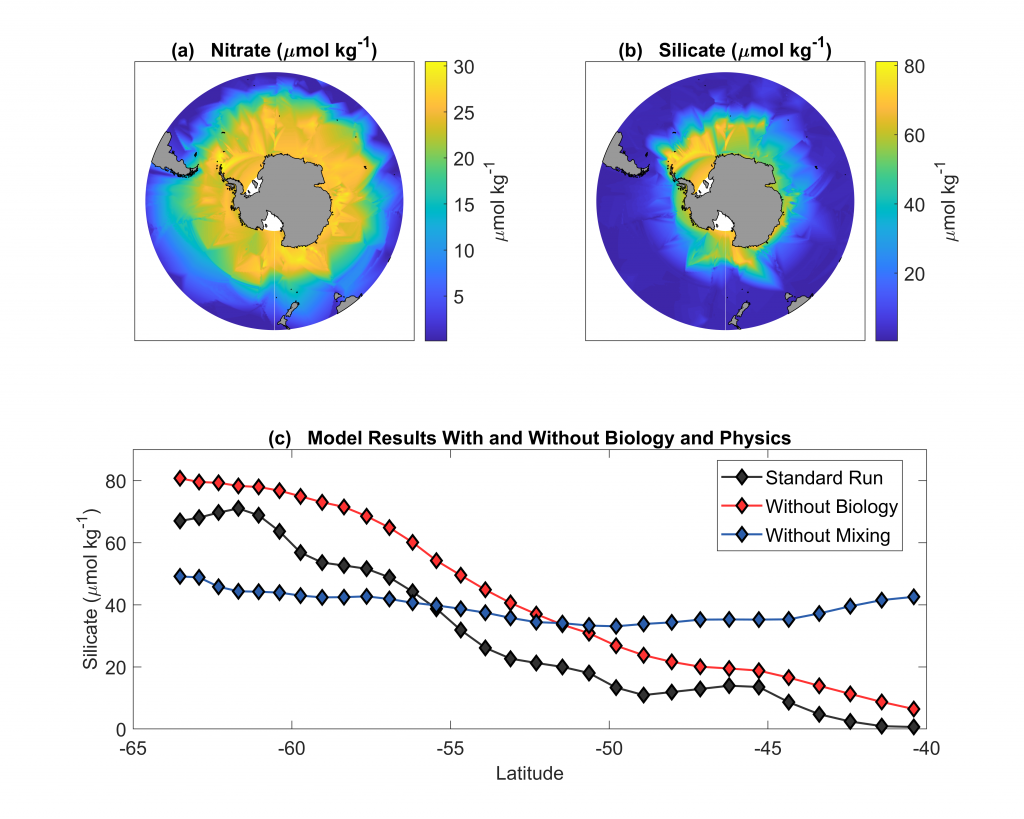

Diatoms are the most important primary producers in the ocean and play an important role in transferring carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere into the deep ocean. Their most conspicuous feature is a silica shell formed around their cells. A comprehensive study published in Nature dove deep into the impacts of ocean acidification on diatoms and biogeochemical cycling. Their analyses of data from experiments, field observations, and model simulations suggest that ocean acidification could drastically reduce diatom populations. As a result of lower seawater pH, the silica shells of diatoms dissolve more slowly. However, this is not an advantage—it causes diatom shells to sink into deeper water layers before chemically dissolving and being converted back into the inorganic nutrient silicic acid. This means this nutrient is more efficiently exported to the deep ocean and so becomes scarcer in the light-flooded surface layer where diatoms require it to form new shells. Ultimately, this loss of silica from the surface ocean causes a global decline in diatoms, reaching -10% by the year 2100 and -26% by 2200. Since diatoms are one of the most important plankton groups in the ocean, their decline could lead to a significant shift in the marine food web or even a change in the ocean carbon sink.

This finding is in sharp contrast to the previous consensus of ocean research, which sees calcifying organisms as losers, but diatoms being little affected, or even a winner of ocean acidification. This also highlights the uncertainties in predicting ecological impacts of climate change and how small-scale effects can lead to ocean-wide changes with unforeseen and far-reaching consequences for marine ecosystems and matter cycles.

Authors:

Jan Taucher (GEOMAR, Kiel, Germany)

Lennart T. Bach (University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia)

Friederike Prowe (GEOMAR, Kiel, Germany)

Tim Boxhammer (GEOMAR, Kiel, Germany)

Karin Kvale (GNS Science, Lower Hutt, New Zealand)

Ulf Riebesell (GEOMAR, Kiel, Germany)