Whether we aim to disentangle anthropogenic driven trends from naturally variability or we want to assess and improve our ocean model’s capabilities to correctly display changes in time, all require high-quality observational data from multiple fixed time-series data. Until now access to these data was difficult, time-consuming, and often required solving multiple data challenges before these data were fit for the purpose. Following the successful examples set by well-known ocean synthesis products, the idea for SPOTS – the Synthesis Product for Ocean Time-Series – was born from this need to address these challenging.

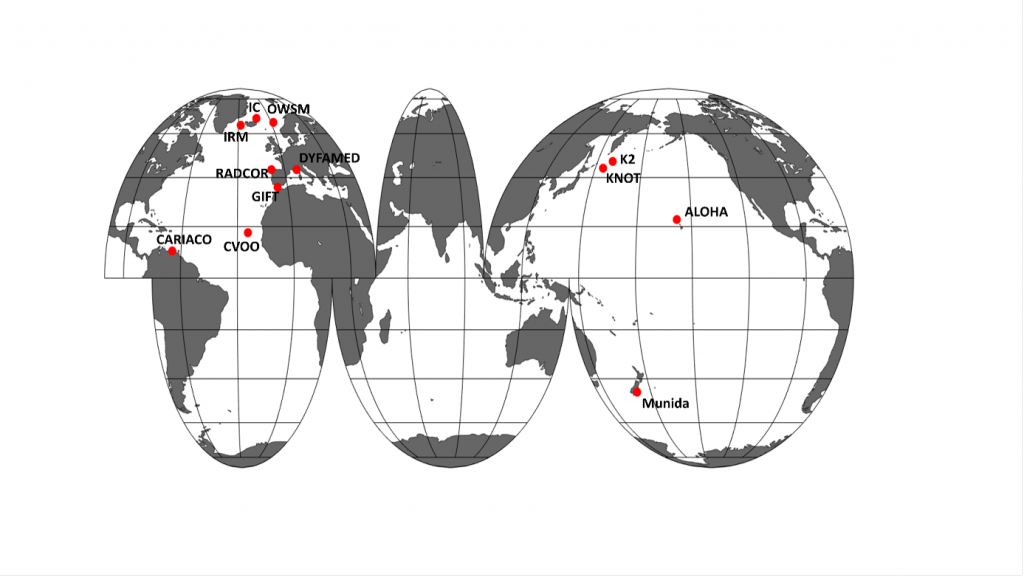

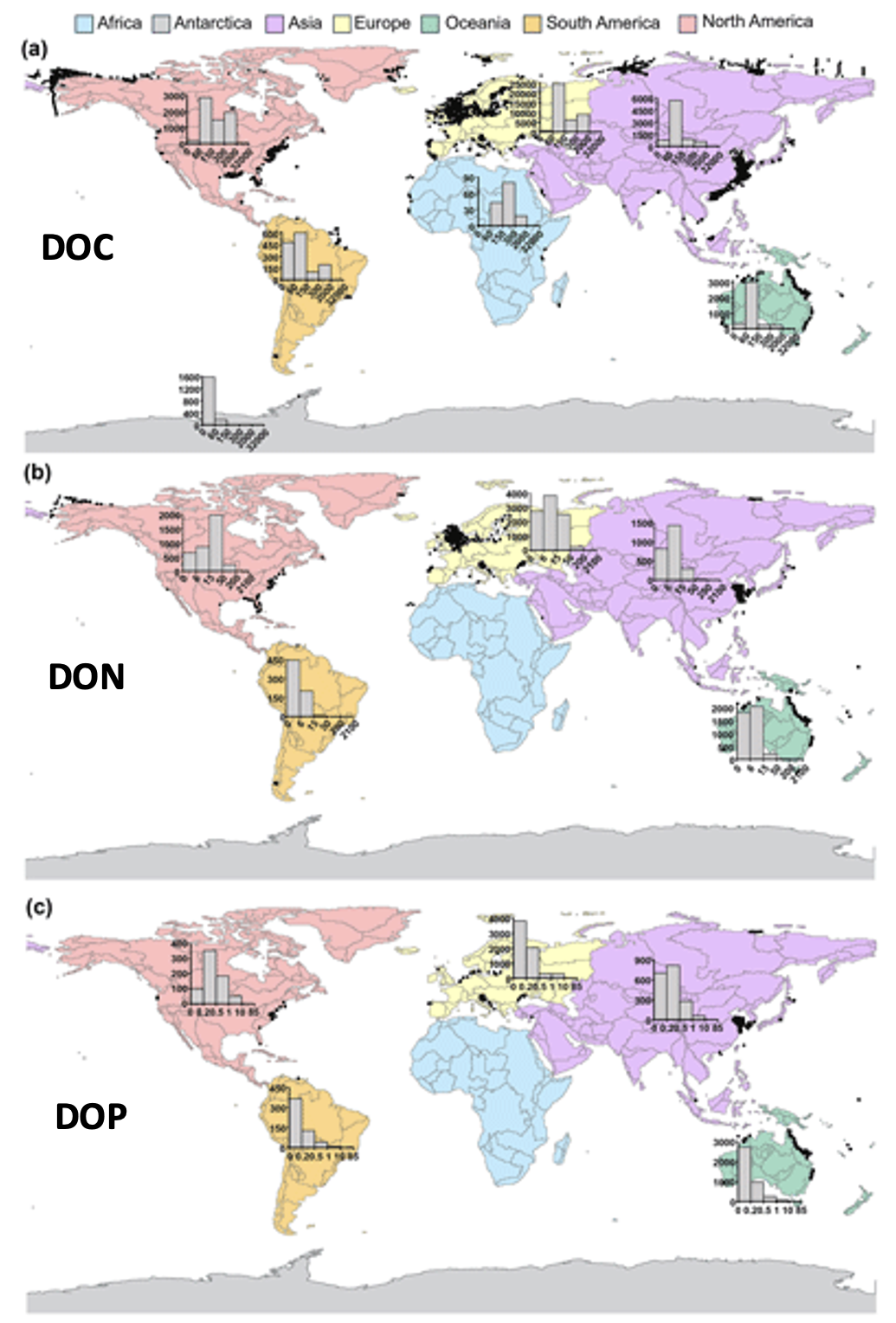

The recently published SPOTS pilot provides biogeochemical essential ocean variables from 12 ship-based fixed time-series scattered around the globe covering the period from 1983 until 2021. An extensive quality assessment enables the straightforward detection of method changes, and in combination with further introduced data quality indicators, the pilot enhances the inter- and intra-station comparability of the included time-series stations. The stations in SPOTS represent unique open ocean and coastal marine environments in the Atlantic, Pacific, Mediterranean, Caribbean, and the Nordic Seas. More than 100,000 water samples are harmonized into one consistent, FAIR, and readily available data synthesis product.

The SPOTS pilot drastically reduces the amount of time needed to obtain high quality and comparable time-series data from multiple programs around the globe. SPOTS facilitates a variety of applications that benefit from the collective value of biogeochemical time-series observations, complementing relevant products for the global ocean that don’t offer the temporal variability and quality of data that fixed time-series programs have. This pilot gives a first glance of what SPOTS has to offer and hopefully many updates of a sustained time-series living data product, SPOTS, will follow.

Read more in the SPOTS paper and access data via BCODMO at https://www.bco-dmo.org/dataset/896862.