“So, in the sea, there are certain objects concerning which one would be at a loss to determine whether they be animal or vegetable.” Aristotle, The History of Animals

Our understanding of marine ecosystems is strongly influenced by the terrestrial macroscopic world we see around us. For example, the distinction between phytoplankton and zooplankton reflects the very familiar divide between plants and animals. Mixotrophs are organisms that blur this distinction by combining photosynthetic carbon fixation and the uptake of inorganic nutrients with the ingestion of living prey (1). In the macroscopic terrestrial realm, the obvious examples of mixotrophs are the carnivorous plants. These organisms are so well known because they confound the otherwise clear divide between autotrophic plants and heterotrophic animals – in terrestrial environments, mixotrophs are the exception rather than the rule. There appear to be numerous reasons for this dichotomy involving constraints on surface area to volume ratios, the energetic demands of predation, and access to essential nutrients and water. Without dwelling on these aspects of macroscopic terrestrial ecology, it appears that many of the most important constraints are relaxed in aquatic microbial communities. Plankton have no need for the fixed root structures that would prevent motility, and in the three-dimensional fluid environment, they are readily exposed to both inorganic nutrients and prey. In addition, their small size and high surface area to volume ratios increase the potential efficiency of light capture and nutrient uptake. As such, mixotrophy is a common and widely recognised phenomenon in marine ecosystems. It has been identified in a very broad range of planktonic taxa and is found throughout the eukaryotic tree of life. Despite its known prevalence, the potential impacts of mixotrophy on the global cycling of nutrients and carbon are far from clear. In this article, I discuss the ecological niche and biogeochemical role of mixotrophs in marine microbial communities, describing some recent advances and identifying future challenges.

A ubiquitous and important strategy

Mixotrophy appears to be a very broadly distributed trait, appearing in all marine biomes from the shelf seas (2) to the oligotrophic gyres (3), and from the tropics (4) to the polar oceans (5). Within these environments, mixotrophy is often a highly successful strategy. For example, in the subtropical Atlantic, mixotrophic plankton make up >80% of the pigmented biomass, and are also responsible for 40-95% of grazing on bacteria (3, 4). Similar abundances and impacts have also been observed in coastal regions (2, 6).

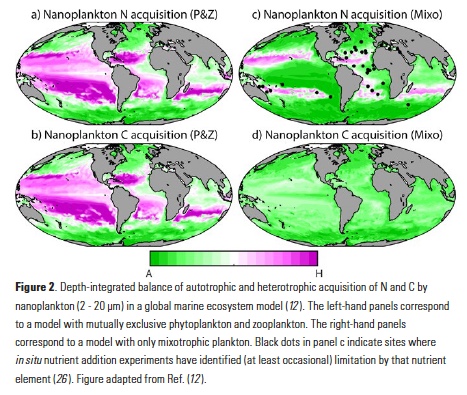

How does the observed prevalence of mixotrophy affect the biogeochemical and ecological function of marine communities? To understand the potential answers to this question, it is helpful to review the constraints associated with the assumption of a strict dichotomy between autotrophic phytoplankton and heterotrophic zooplankton. Within this paradigm, primary production is restricted to the base of the food web, tightly coupled to the supply of limiting nutrients. Furthermore, the vertical export of

carbon is limited by the supply of exogenous (or “new”) nutrients (7), since any local regeneration of nutrients from organic matter is also associated with the local remineralisation of dissolved inorganic carbon. Energy and biomass are passed up the food web, but the transfer across trophic levels is highly inefficient (8) (Fig. 1) because the energetic demands of strictly heterotrophic consumers can only be met by catabolic respiration.

In the mixotrophic paradigm, several of these constraints are relaxed. Primary production is no longer exclusively dependent on the supply of inorganic nutrients because mixotrophs can support photosynthesis with nutrients derived from their prey. This mechanism takes advantage of the size-structured nature of marine communities (9), with larger organisms avoiding competitive exclusion by eating their smaller and more efficient competitors (10-12). In addition, the energetic demands of mixotrophic consumers can be offset by phototrophy, leading to increased efficiency of carbon transfer through the food web (Fig. 1). These two mechanisms dictate that mixotrophic ecosystems can fix and export more carbon for the same supply of limiting nutrient, relative to an ecosystem strictly divided between autotrophic phytoplankton and heterotrophic zooplankton (12).

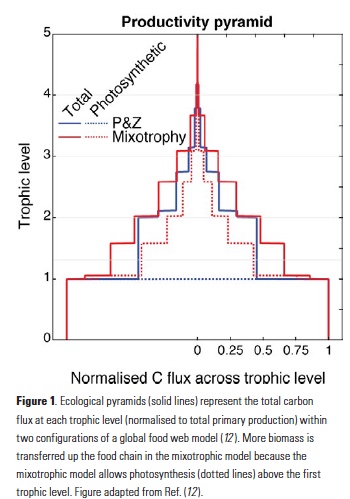

The trophic flexibility associated with mixotrophy appears likely to have a profound effect on marine ecosystem function at the global scale. Fig. 2 contrasts the simulated fluxes of carbon and nitrogen through the intermediate nanoplankton (2-20 μm diameter) size class of a global ecosystem model (12). The left-hand maps show the balance of autotrophic and heterotrophic resource acquisition in a model with mutually exclusive phytoplankton and zooplankton. At low latitudes and especially in the

oligotrophic subtropical gyres, the inorganic nitrogen supply is acquired almost exclusively by the smallest and most competitive phytoplankton (not shown). This leaves an inadequate supply for larger and less competitive phytoplankton, and as such, the larger size classes are dominated by zooplankton (as indicated by the purple shading in Fig. 2a, b). In the more productive polar oceans and upwelling zones, grazing pressure prevents the smaller phytoplankton from exhausting the inorganic nitrogen supply, leaving enough for the larger phytoplankton to thrive in these regions (as indicated by the green shading).

The right-hand maps in Fig. 2 show the balance of autotrophic and heterotrophic resource acquisition in the intermediate size-class of an otherwise identical model containing only mixotrophic plankton. As in the model with mutually exclusive phytoplankton and zooplankton, the inorganic nitrogen supply in the oligotrophic gyres is exhausted by the smallest phytoplankton (see the purple shading in Fig. 2c). However, Fig. 2d indicates that this is not enough to stop photosynthetic carbon fixation among the mixotrophic nanoplankton. The nitrogen acquired from prey is enough to support considerable photosynthesis in a size class for which phototrophy would otherwise be impossible. For the same supply of inorganic nutrients, this additional supply of organic carbon serves to enhance the transfer of energy and biomass through the microbial food web, increasing community carbon:nutrient ratios and leading to as much as a three-fold increase in mean organism size and a 35% increase in vertical carbon flux (12).

Trophic diversity and ecosystem function

Marine mixotrophs are broadly distributed across the eukaryotic tree of life (13). The ability to combine photosynthesis with the digestion of prey has been identified in ciliates, cryptophytes, dinoflagellates, foraminifera, radiolarians, and coccolithophores (14). Perhaps the only major group with no identified examples of mixotrophy are the diatoms, which have silica cell walls that may hinder ingestion of prey. While some mixotroph species are conceptually more like plants (that eat), others are more like animals (that photosynthesise). A number of conceptual models have been developed to account for this observed diversity. One scheme (15) identified three primarily autotrophic groups that use prey for carbon, nitrogen or trace compounds, and two primarily heterotrophic groups that use photosynthesis to delay starvation or to increase metabolic efficiency. More recently, an alternative classification (16, 17) identified three key groups on a spectrum between strict phototrophy and strict phagotrophy. According to this classification, primarily autotrophic mixotrophs can synthesise and fully regulate their own chloroplasts, whereas more heterotrophic forms must rely on chloroplasts stolen from their prey. Among this latter group, the more specialised species exploit only a limited number of prey species, but can manage and retain stolen chloroplasts for relatively long periods. In contrast, generalist mixotrophs target a much wider range of prey, but any stolen chloroplasts will degrade within a matter of hours or days (18).

This diversity of trophic strategies is clearly more than most biogeochemical modellers would be prepared to incorporate into their global models. Nonetheless, many of the conceptual groups identified above are associated with the ability of mixotrophs to rectify the often-imbalanced supply of essential resources in marine ecosystems (19). This is clearly relevant to the coupling of elemental cycles in the ocean, and it appears likely that the relative abundance of different trophic strategies can impact the biogeochemical function of marine communities (1, 20). For example, recent work suggests that a differential temperature sensitivity of autotrophic and heterotrophic processes can push mixotrophic species towards a more heterotrophic metabolism with increasing temperatures (21). An important goal is therefore to accurately quantify and account for the global-scale effects of mixotrophy on the transfer of energy and biomass through the marine food web and the export of carbon into the deep ocean. We also need to assess how these effects might be sensitive to changing environmental conditions in the past, present, and future.

These processes are not resolved in most contemporary models of the marine ecosystem, which are often based on the representation of a limited number of discrete plankton functional types (22). In terms of resolving mixotrophy, it is not the case that these models have overlooked the one mixotrophic group. Instead, it may be more accurate to say that the groups already included have been falsely divided between two artificially distinct categories. As such, modelling mixotrophy in marine ecosystems is not just a case of increasing complexity by adding an additional mixotrophic component. Instead, progress can be made by understanding the position, connectivity, and influence of mixotrophic and non-mixotrophic organisms within the food web as an emergent property of their environment, ecology, and known eco-physiological traits. This is not a simple task, but progress might be made by identifying the fundamental traits that underpin the observed diversity of functional groups. To this end, a recurring theme in mixotroph ecology is that plankton exist on a spectrum between strict autotrophy and strict heterotrophy (14, 23, 24). Competition along this spectrum is typically framed in terms of the costs and benefits of different modes of nutrition. Accurate quantification of these costs and benefits should allow for a much clearer understanding of the trade-offs between different mixotrophic strategies (25), and how they are selected in different environments. In the future, a combination of culture experiments, targeted field studies, and mathematical models should help to achieve this goal, such that this important ecological mechanism can be reliably and parsimoniously incorporated into global models of marine ecosystem function.

Author

Ben Ward (University of Bristol)

References

1. Stoecker, D. K., Hansen, P. J., Caron, D. A. & Mitra, Annual Rev. Marine Sci. 9, forthcoming (2017).

2. Unrein, F., Gasol, J. M., Not, F., Forn, I. & Massana, R. The ISME Journal 8, 164–176 (2013).

3. Zubkov, M. V. & Tarran, G. A. Nature 455, 224–227 (2008).

4. Hartmann, M. et al. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 5756–5760 (2012). doi:10.1073/pnas.1118179109

5. Gast, R. J. et al. J. Phycol. 42, 233–242 (2006).

6. Havskum, H. & Riemann, B. Marine Ecol. Prog. Ser. 137, 251–263 (1996).

7. Dugdale, R. C. & Goering, J. J. Limnol. Oceanogr. 12, 196–206 (1967).

8. Lindeman, R. L. Ecol. 23, 399–417 (1942).

9. Sieburth, J. M., Smetacek, V. & Lenz, J. Limnol. Oceanogr. 23, 1256–1263 (1978).

10. hingstad, T. F., Havskum, H., Garde, K. & Riemann, B. Ecol. 77, 2108–2118 (1996).

11. Våge, S., Castellani, M., Giske, J. & Thingstad, T. F. Aquatic Ecol. 47, 329–347 (2013).

12. Ward, B. A. & Follows, M. J. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 113, 2958–2963 (2016).