Due to a sparsity of in‐situ observations and the computational burden of eddy‐resolving global simulations, there has been little analysis on how mesoscale processes (e.g., eddies, meanders—lateral scales of 10s to 100s km) influence air‐sea CO2 fluxes from a global perspective. Recently, it became computationally feasible to implement global eddy‐resolving [O (10) km] ocean biogeochemical models. Many questions related to the influence of mesoscale motions on CO2 fluxes remain open, including whether ocean eddies serve as hotspots for CO2 sink or source in specific dynamic regions.

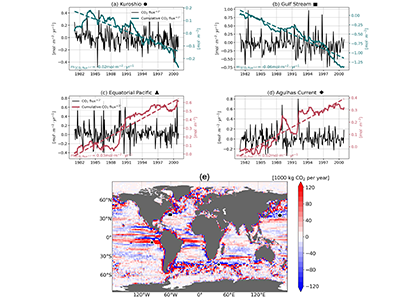

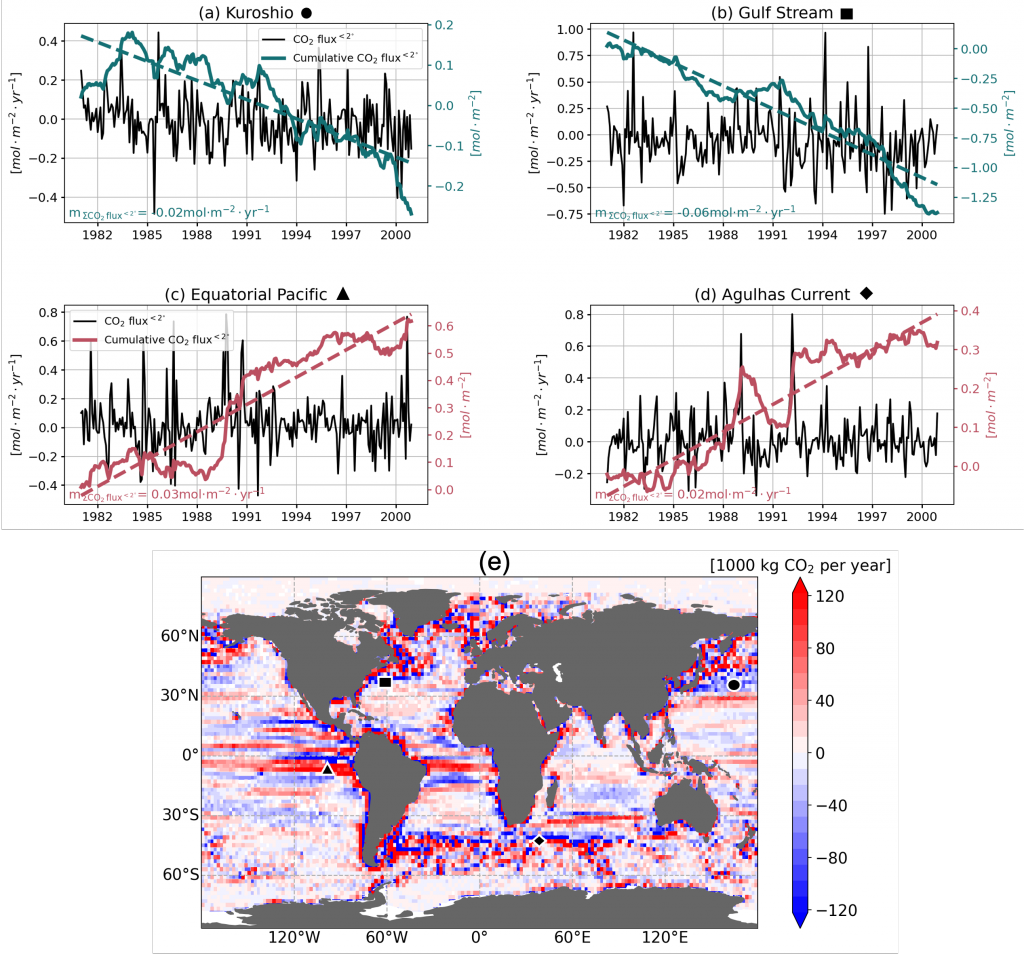

A recent study in Geophysical Research Letters investigated the contribution of ocean mesoscale variability to air-sea CO2 fluxes by analyzing the CO2 flux anomaly within the mesoscale band using a coarse-graining approach in a global eddy-resolving biogeochemical simulation. We found that in eddy-rich mid-latitude regions, ocean mesoscale variability can contribute to over 30% of the total CO2 flux variability. The cumulative net CO2 flux associated with mesoscale motions is on the order of 105 tC per year. The global pattern of cumulative mesoscale-related CO2 flux exhibits significant spatial heterogeneity, with the highest values in western boundary currents, the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, and the equatorial Pacific. The local distribution of cumulative mesoscale-related CO2 flux displays zonal bands alternate between positive (a net source) and negative (a net sink) due to the meandering nature of ocean mesoscale currents, which is related to local relative vorticity and the background cross-stream pCO2 gradient.

Figure caption. Mesoscale (<nominal 2 degree) contribution to air‐sea CO2 flux (F<2°CO2)in the model. (a)–(d) Monthly time series of F<2°CO2 (black lines) and cumulative F<2°CO2 (green/red solid lines) in four locations marked in (e). Dashed lines are the least squares regression of cumulative flux for the period 1982–2000; slopes are indicated in the bottom left; (e) Blue colors imply a CO₂ sink, and red colors represent a source. The figure shows the global distribution of the regressed slopes of cumulative F<2°CO2. Units are converted from mol m-2 per year to kg of CO2 per year using the atomic mass of CO2. This figure shows significant spatial heterogeneity of mesoscale-modulated CO2 flux, showing contributions to both CO₂ sources and sinks across different regions of the ocean, with a magnitude on the order of 105 tC per year.

Authors

Yiming Guo (Yale University; now at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Mary-Louise Timmermans (Yale University)