Scientists have long known the role of Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) in Southern Ocean ecosystems. Evidence is gathering about krill’s biogeochemical importance through releasing millions of faecal pellets in swarms and stimulating primary production through nutrient excretion. Here, we explore and synthesise the known impacts that this highly abundant and rather large species has on the environment. Krill exemplify how metazoa can play a dominant role in shaping ocean biogeochemistry, thus providing additional motivation for protecting certain harvested species.

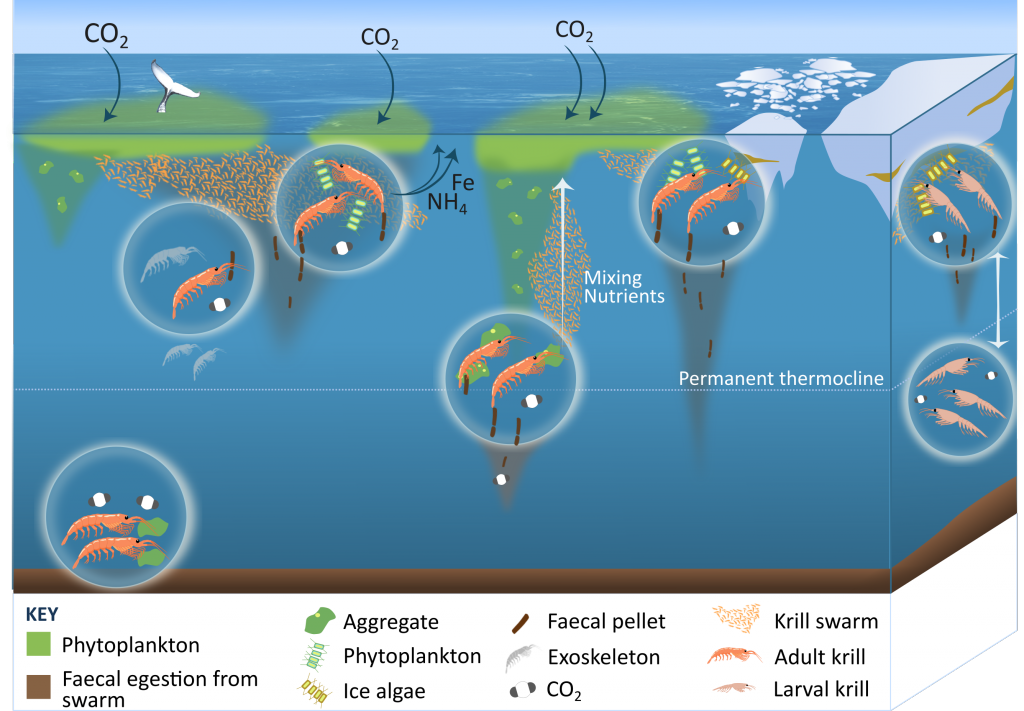

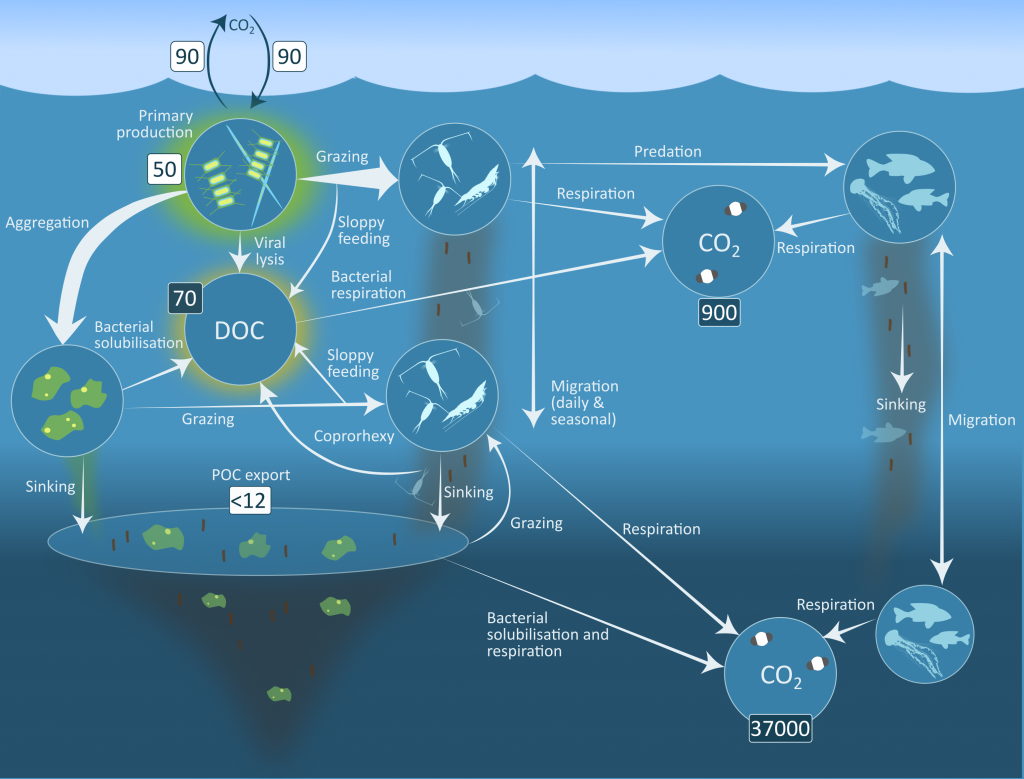

Figure 1: The ecological roles of krill in Southern Ocean biogeochemical cycles, including releasing faecal pellets, excreting nutrients whilst grazing, and larval krill migrating throughout the water column, shedding exoskeletons, and feeding on the seabed.

A review published in Nature Communications uncovers at least 13 possible pathways by which Antarctic krill either influence the carbon sink or release fertilizing nutrients (Figure 1). Their large size (up to 7 cm) and swarming nature (millions of krill aggregate) enable krill to strongly impact ocean biogeochemistry. Swarms release large numbers of faecal pellets, overwhelming detritivores and resulting in a large sink of faecal carbon. Krill may physically mix nutrients from the deep ocean and become a decades-long carbon store in whale biomass. Antarctic krill larvae, which live near the sea-ice, undergo deeper diel vertical migrations compared to adult Antarctic krill (400 m vs. 200 m), so any carbon respired or faecal pellets released by larvae could remain in the deep ocean longer than those released by adult krill at a shallower depth; the larval krill contribution to carbon export has not been quantified. Furthermore, it is currently unknown how many krill larvae are removed from the Antarctic krill fishery as by-catch. Perhaps the biggest challenge in constraining the role of krill (adult and larvae) in biogeochemical cycles is our limited capacity to quantify the abundance and biomass of Antarctic krill, since shipboard sampling methods (nets or acoustics) have limited spatial and temporal coverage. Ultimately, the Southern Ocean is an important physical AND biological sink of carbon, and we must consider the role krill and other animals have in this cycle.

Figure 2: Processes in the biological carbon pump including the sinking of dead phytoplankton aggregates, zooplankton, krill and fish faecal pellets and dead animals. Microbial remineralisation is depicted through the return of particulate organic carbon to dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and eventually carbon dioxide.

Authors:

Emma Cavan (Imperial College London and University of Tasmania)

Anna Belcher (British Antarctic Survey)

Angus Atkinson (Plymouth Marine Laboratory)

Simeon Hill (British Antarctic Survey)

So Kawaguchi (Australian Antarctic Division)

Stacey McCormack (University of Tasmania)

Bettina Meyer (Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research and University of Oldenburg)

Stephen Nicol (University of Tasmania)

Lavenia Ratnarajah (University of Liverpool)

Katrin Schmidt (University of Plymouth)

Deborah Steinberg (Virginia Institute of Marine Science)

Geraint Tarling (British Antarctic Survey)

Philip Boyd (University of Tasmania and Antarctic Climate and Ecosystems Cooperative Research Centre)