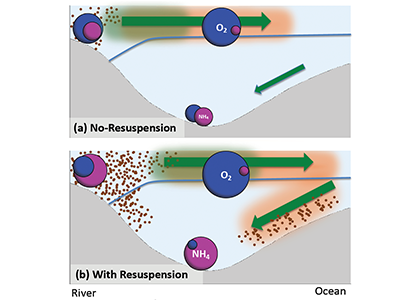

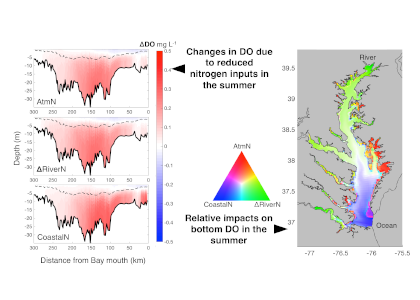

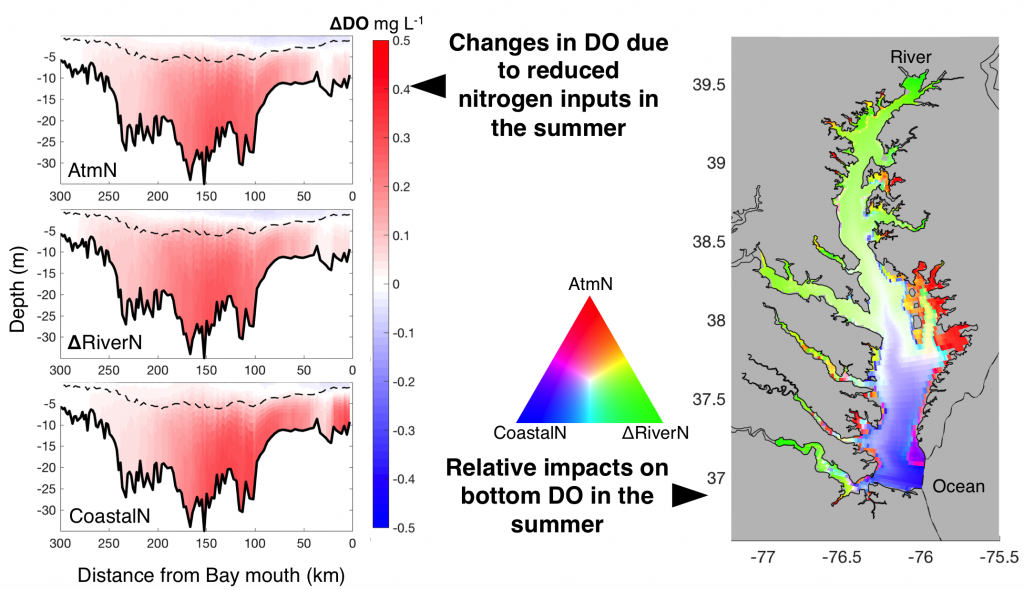

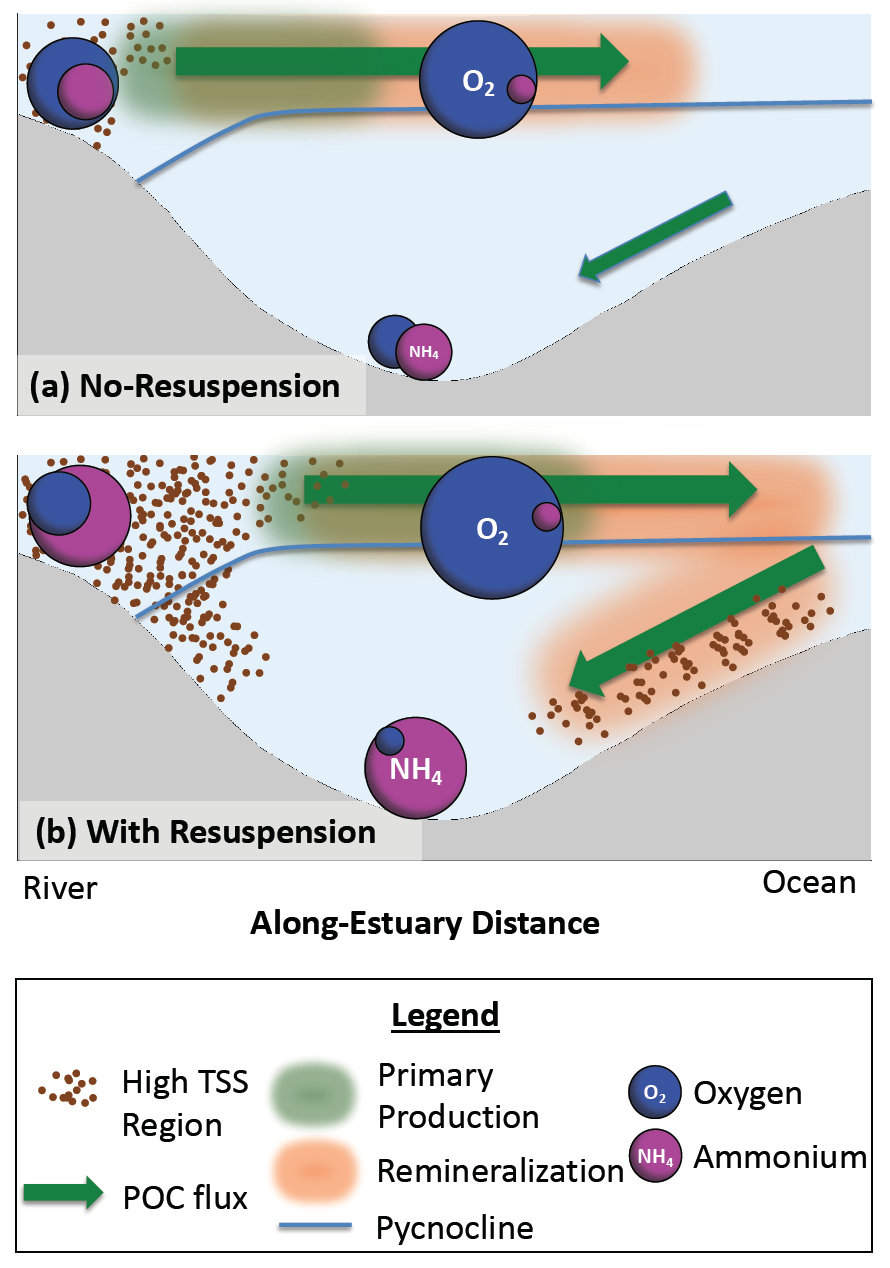

Sediment processes, including resuspension and transport, affect water quality in estuaries by altering light attenuation, primary productivity, and organic matter remineralization, which then influence oxygen and nitrogen dynamics. In a recent paper published in Estuaries and Coasts, the authors quantified the degree to which sediment resuspension and transport affected estuarine biogeochemistry by implementing a coupled hydrodynamic-sediment transport-biogeochemical model of the Chesapeake Bay. By comparing summertime model runs that either included or neglected seabed resuspension, the study revealed that resuspension increased light attenuation, especially in the northernmost portion of the Bay, which subsequently shifted primary production downstream (Figure 1). Resuspension also increased remineralization in the central Bay, which experienced higher organic matter concentrations due to the downstream shift in primary productivity. When combined with estuarine circulation, these resuspension-induced shifts caused oxygen to increase and ammonium to increase throughout the Bay in the bottom portion of the water column. Averaged over the channel, resuspension decreased oxygen by ~25% and increased ammonium by ~50% for the bottom water column. Changes due to resuspension were of the same order of magnitude as, and generally exceeded, short-term variations within individual summers, as well as interannual variability between wet and dry years. This work highlights the importance of a localized process like sediment resuspension and its capacity to drive biogeochemical variations on larger spatial scales. Documenting the spatiotemporal footprint of these processes is critical for understanding and predicting the response of estuarine and coastal systems to environmental changes, and for informing management efforts.

Figure 1: Schematic of how resuspension affects biogeochemical processes based on HydroBioSed model estimates for Chesapeake Bay.

Authors:

Julia M. Moriarty (University of Colorado Boulder)

Marjorie A. M. Friedrichs (Virginia Institute of Marine Science)

Courtney K. Harris (Virginia Institute of Marine Science)

Also see the Geobites piece “Muddy waters lead to decreased oxygen in Chesapeake Bay” on this publication, by Hadley McIntosh Marcek