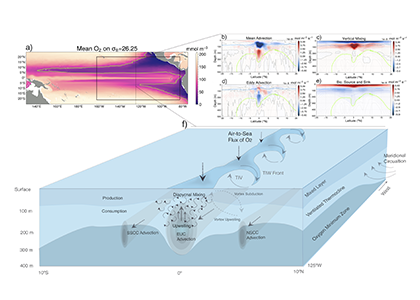

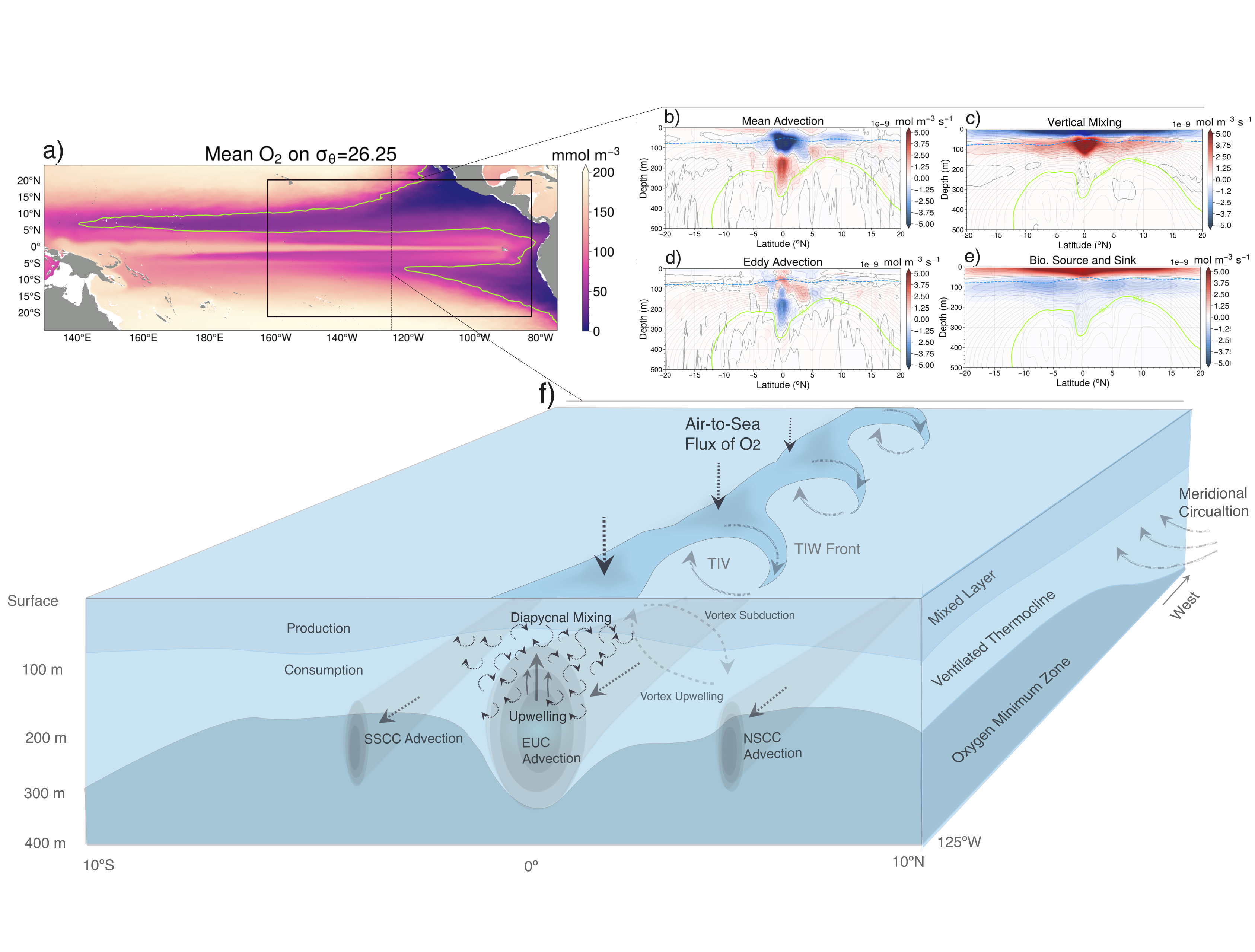

What balances oxygen removal in the equatorial Pacific? For a long time, oxygen in the eastern and central tropical Pacific was assumed to be mainly supplied by the large-scale advection of remotely ventilated waters via the equatorial current system and meridional circulation. A recent study used an eddy-resolving simulation of a global ocean model to show that turbulent mixing and its regulation by mesoscale eddies play a critical role in balancing oxygen removal (by consumption and upwelling) in the upper thermocline. Deeper in the water column, mean advection by the zonal currents and meridional circulation dominates. This mixing is tightly regulated by tropical instability waves, which intensify the shear between the equatorial currents and enhance the downward turbulent mixing flux of oxygen into the thermocline. Mesoscale phenomena thus play an indirect yet critical role as a local pathway of ventilation in this region. Testing these model-based hypotheses in the real ocean through dedicated field studies and long-term observations is needed to advance our understanding of the observed expansion of the oxygen deficient zones (ODZs) and model their future trajectory in a warmer and more stratified ocean.

Figure: The main processes that set the mean structure of oxygen in the equatorial Pacific are assessed in an eddy resolving simulation of the Community Earth System Model (CESM). Panel a shows the climatological oxygen distribution on the 26.25 isopycnal in CESM. Panels b-e show the contribution of advection by mean circulation and eddies, vertical mixing, and production and consumption. These processes are illustrated in panel f). Figure adapted from Eddebbar et al (2024).

Authors

Yassir A. Eddebbar (Scripps Institution of Oceanography)

Daniel B. Whitt (NASA Ames)

Ariane Verdy, (Scripps Institution of Oceanography)

Matthew R. Mazloff (Scripps Institution of Oceanography)

Aneesh C. Subramanian (CU Boulder)

Matthew C. Long, (National Center for Atmospheric Research)