The C:N:P stoichiometry of global ocean biological production is the gear by which marine biology turns the wheels of the global ocean carbon cycle. From the days of Alfred Redfield until fairly recently, this stoichiometry was assumed a constant in ocean biogeochemistry (e.g., the Redfield ratio). Traditional stoichiometry would predict a carbon export production decline in the future, as warming is generally expected to enhance water column stratification and diminish the vertical supply of nutrients. However, recent observations clearly show that the C:N:P ratio is quite variable: the ratio is higher in oligotrophic waters than in eutrophic waters, and the ratio is higher in cyanobacteria than eukaryotes. How can flexible C:N:P ratio in phytoplankton affect future carbon export?

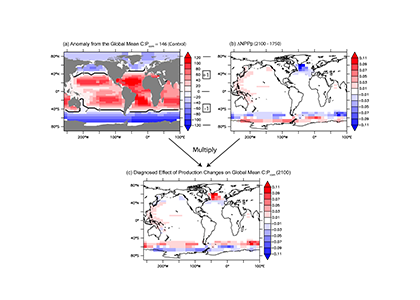

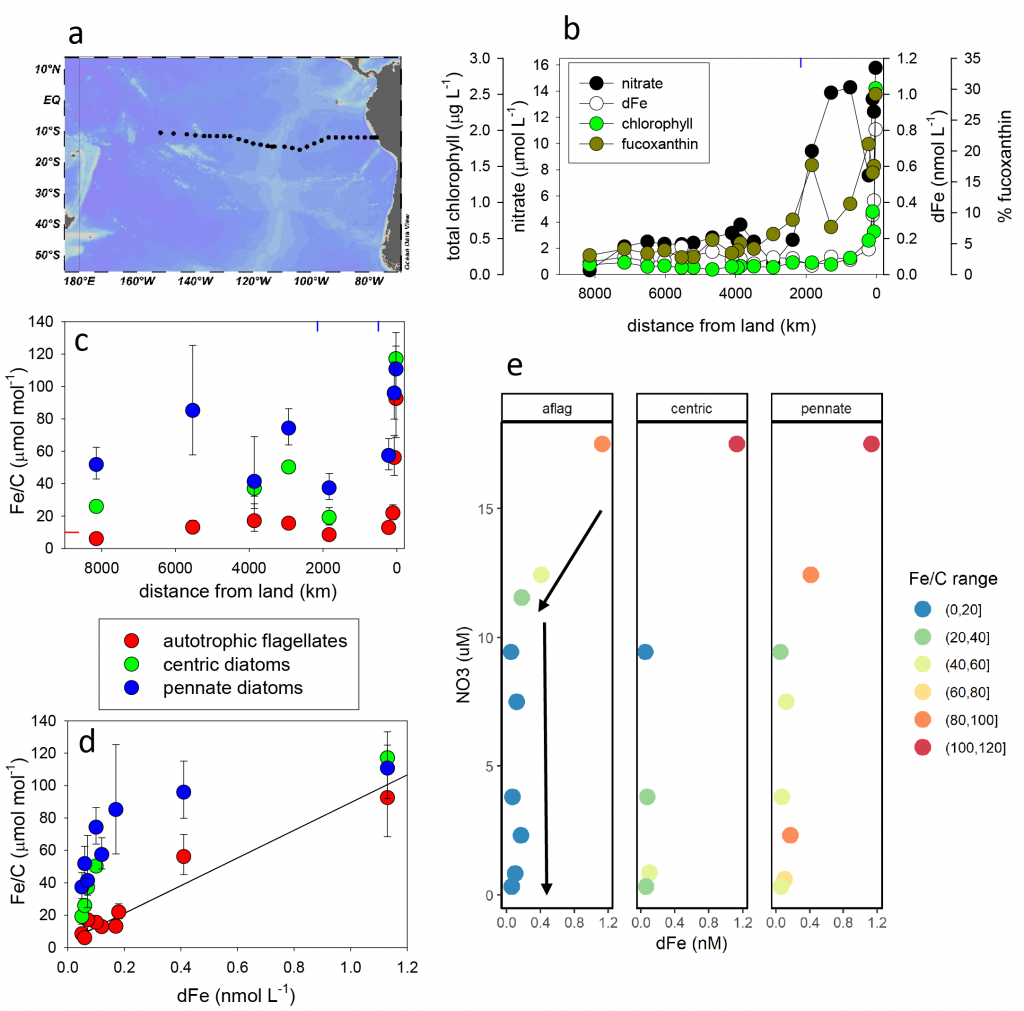

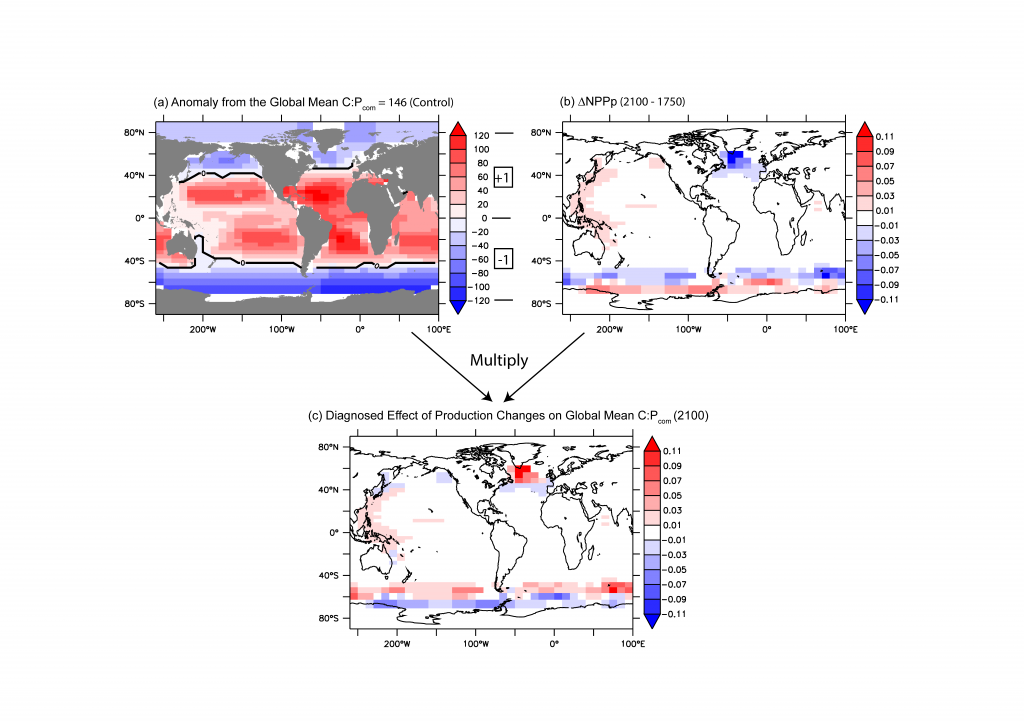

A recent publication in Environmental Research Letters discusses three drivers of global ocean production stoichiometry in the future: physiological response of phytoplankton, changes in phytoplankton community composition, and shifts in the regional production, which the authors focused most on as it is the least explored. The authors carried out global warming experiments using a numerical model of global ocean biogeochemistry that represents flexible C:N:P ratios in multiple phytoplankton types with dependence on ambient N and P concentrations, temperature, and light. These model results indicate the importance of the physiological response of cyanobacteria to warming and of eukaryotes to P depletion in driving a higher C:N:P ratio (Figure 1).

Figure caption: Diagnosed effect of regional production changes on the future global mean C:P ratio. The diagnosis (c) is given by the product of the sign of the effect (a) and the production changes (b). The sign of the effect of the regional production changes is positive (+1) for locations with local C:P > global mean (red) and negative (−1) for locations with C:P < global mean (blue). The diagnosis shows a N-S dipole response in both the Southern Ocean and the North Atlantic, where changes in production both increase and decrease the global C:N:P ratio.

Global production C:N:P ratio can vary by shifting the regional production, even in the absence of any change in phytoplankton stoichiometry or taxonomy. For example, simply increasing the production in polar waters—which typically have low C:N:P ratios (eukaryote-dominant, P-rich, and cold)—will lower the global C:N:P ratio, because the polar production then makes a relatively larger contribution to the global production. In this model, future Antarctic sea ice retreat has this very effect, but is offset by production changes downstream and elsewhere. Current literature indicates substantial uncertainty in the future projection of regional production changes. This study illuminates regional production as a new driver of global export C:N:P ratio and an important area of future investigation.

Authors:

Katsumi Matsumoto (University of Minnesota)

Tatsuro Tanioka (University of Minnesota, now University of California, Irvine)