Dissolved oxygen (O2) is a central observation in oceanography with a long history of relatively high precision measurements and increasing coverage over the 21st century. O2 is a powerful tracer of physical, chemical and biological processes (e.g., photosynthesis and respiration, wave-induced bubbles, mixing, and air-sea diffusion). A commonly used approach to partition the processes controlling the O2 signal relies on concurrent measurements of argon (an inert gas), which has solubility properties similar to O2. However, only a limited fraction of O2 measurements have paired argon measurements.

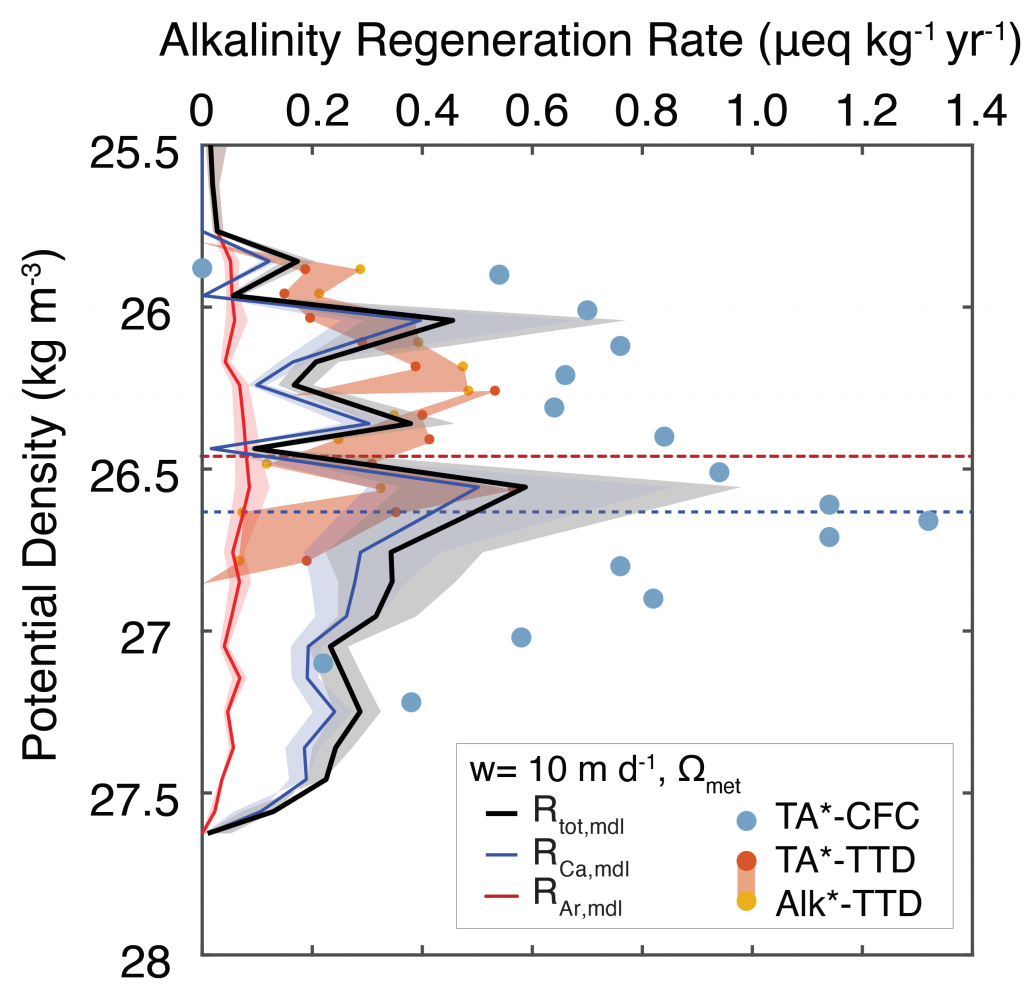

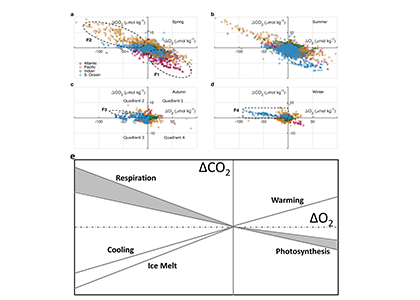

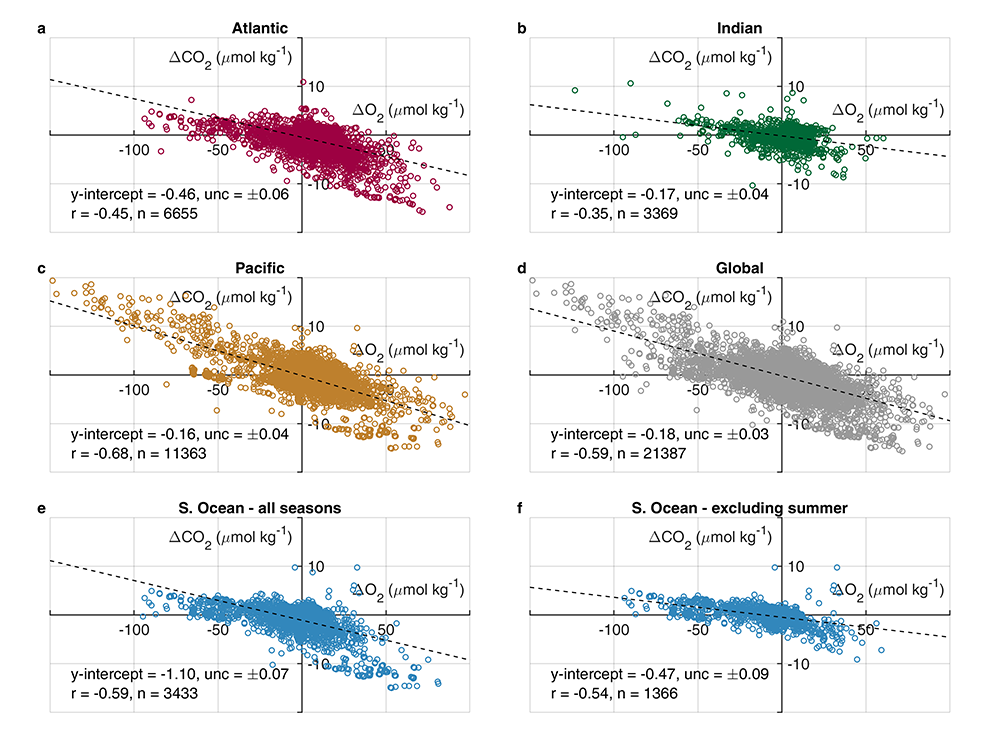

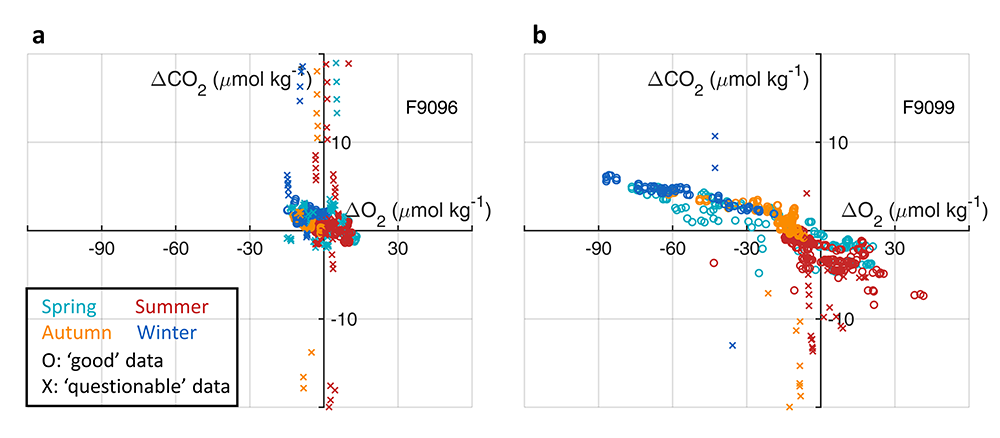

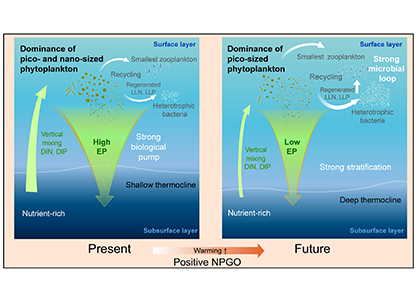

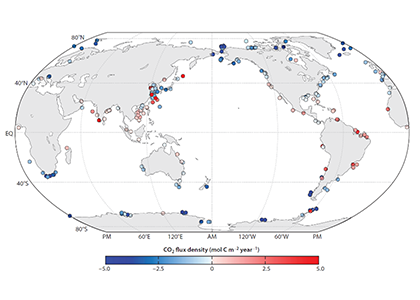

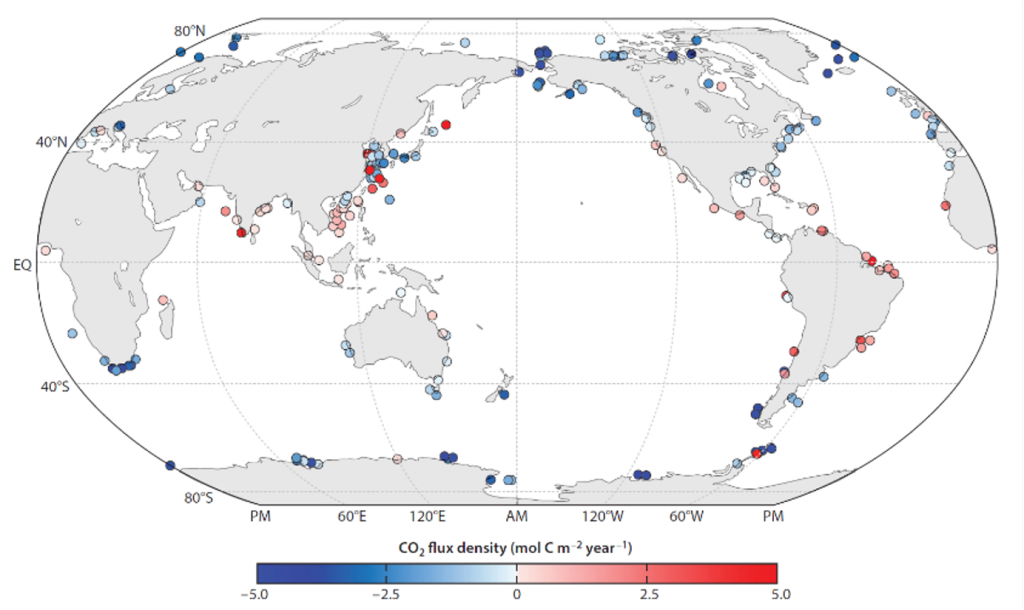

Figure 1. (a) The newly developed empirical model to parameterize the physical oxygen saturation anomaly (ΔO2[phy]) in order to separate the biological contribution from total oxygen, and (b-c) regional, inter-annual, and decadal variability of air-sea gas flux of biological oxygen (F[O2]bio as) reconstructed from the historical dissolved oxygen record.

The long-term objective of this proof-of-concept effort is to estimate from historical oxygen records and a rapidly growing number of O2 measurements on autonomous platforms. In regions where vertical and horizontal mixing is weak, the projected approximates net community production, providing an independent constraint on the strength of the biological carbon pump.

Authors:

Yibin Huang (Duke University)

Rachel Eveleth (Oberlin College)

David (Roo) Nicholson (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Nicolas Cassar (Duke University)