Wildfire frequency, size, and destructiveness has increased over the last two decades, particularly in coastal regions such as Australia, Brazil, and the western United States. While the impact of fire on land, plants, and people is well documented, very few studies have been able to evaluate the impact of fires on ocean ecosystems. A serendipitously planned research cruise one week after the Thomas Fire broke out in California in December 2017 allowed the authors of this study and their colleagues to sample the adjacent Santa Barbara Channel during this devastating extreme fire event.

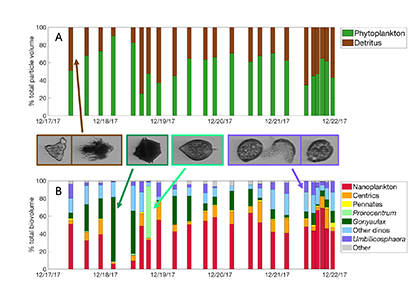

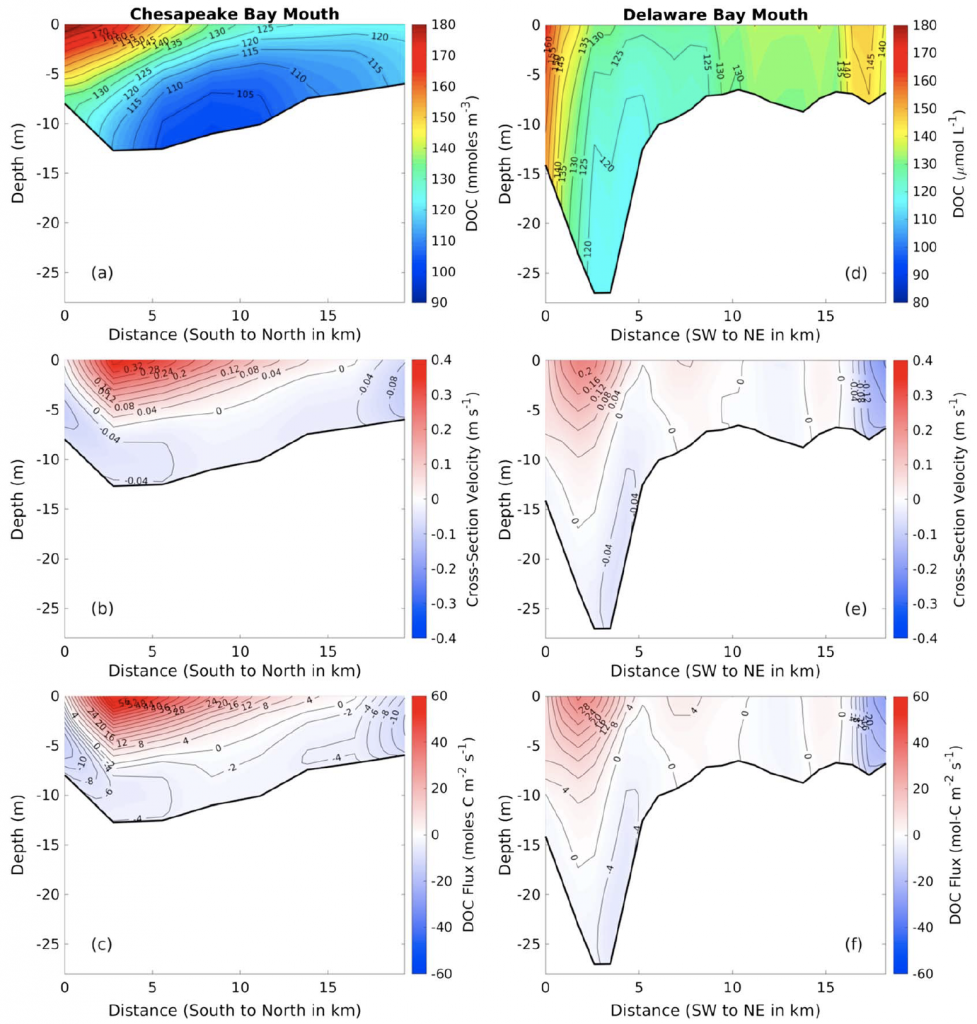

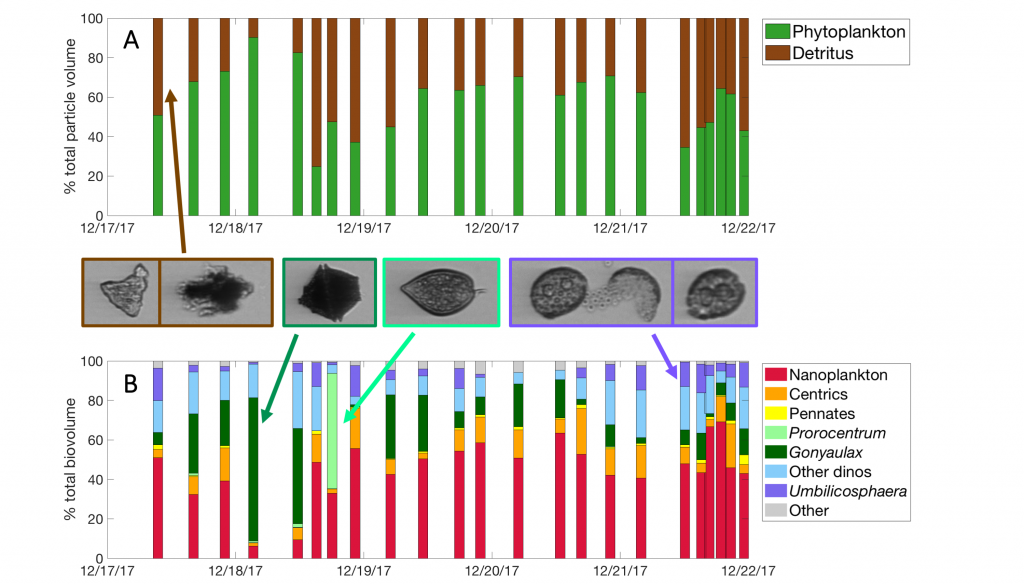

In a recent paper published in Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, the authors describe the phytoplankton community in the Santa Barbara Channel during the Thomas Fire. Phytoplankton community composition was described using a combination of images of phytoplankton from the Imaging FlowCytobot (McLane Labs) and phytoplankton pigments. Dinoflagellates were the dominant phytoplankton group in the surface ocean during the Thomas Fire, according to both methods (Figure 1).

Figure 1. (A) The fraction of total particle volume imaged by the Imaging FlowCytobot (IFCB) comprised of phytoplankton (green) and detritus (brown). Example IFCB images of ash (counted as part of detritus) particles are outlined in brown. (B) The phytoplankton fraction is then further divided by taxonomy, showing the abundance of nano-sized phytoplankton and especially dinoflagellates during the week of sampling. Example IFCB images of Gonyaulax (outlined in dark green), Prorocentrum (outlined in light green), and Umbilicosphaera (outlined in purple) cells are also shown.

While this study was not able to demonstrate a causal relationship between the Thomas Fire and the presence of dinoflagellates, this result is quite different from previous winters in the Santa Barbara Channel, when picophytoplankton and diatoms typically dominate the winter community. The incidence of dinoflagellates in the Santa Barbara Channel in December 2017 was correlated with the warmer-than-average water temperature during this study, which matched observations from other areas along the Central California coast that winter.

At the time this study was conducted, the Thomas Fire was the largest wildfire in California history. Since then, California fires have increased in danger, destruction, and human mortality; the Mendocino Fire complex (summer 2018) and five separate wildfires in summer 2020 exceeded the impacts of the Thomas Fire. With wildfire severity and frequency increasing not only in California but in coastal regions worldwide, this study gives an important first look at the impact of wildfire smoke and ash on oceanic primary productivity and community composition.

Authors:

Sasha Kramer (University of California Santa Barbara)

Kelsey Bisson (Oregon State University)

Alexis Fischer (University of California Santa Cruz)