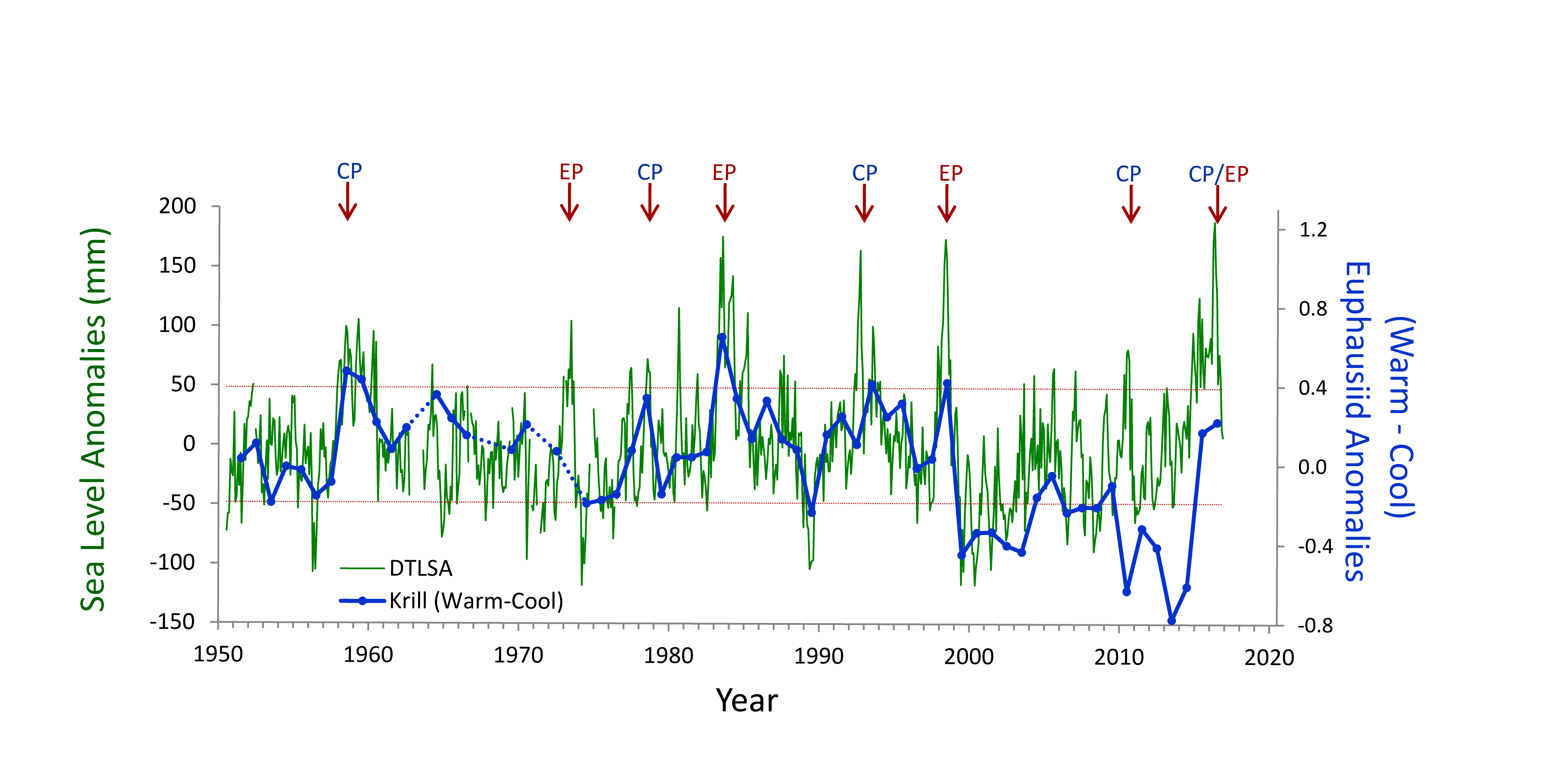

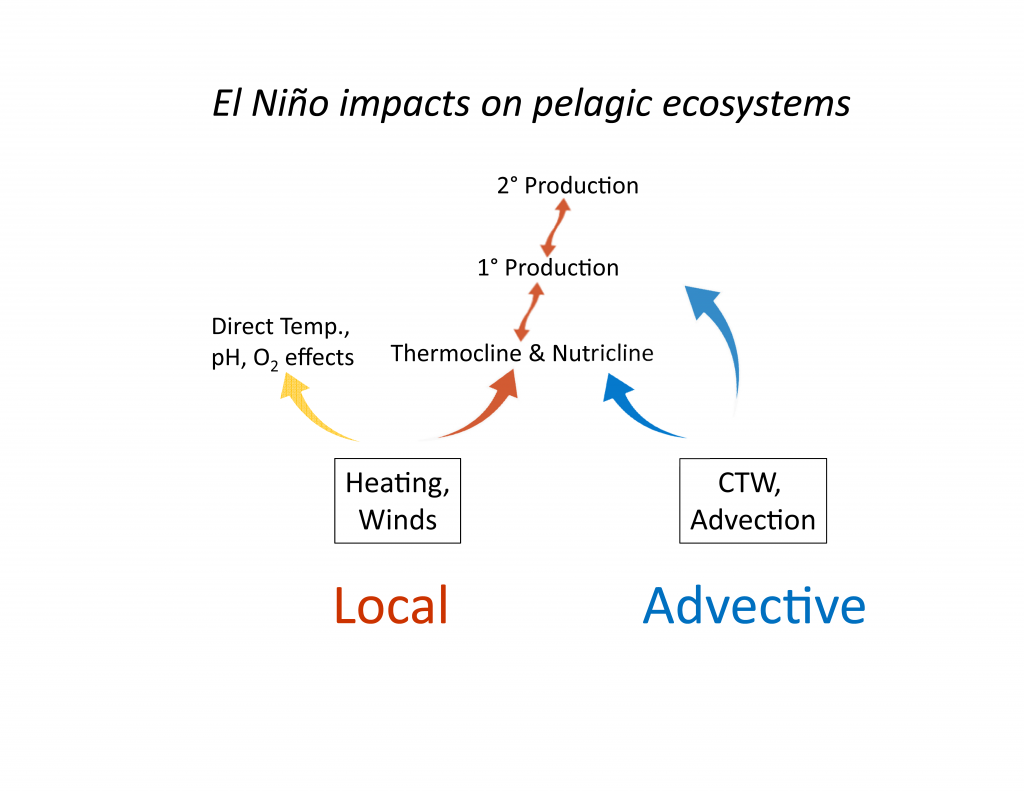

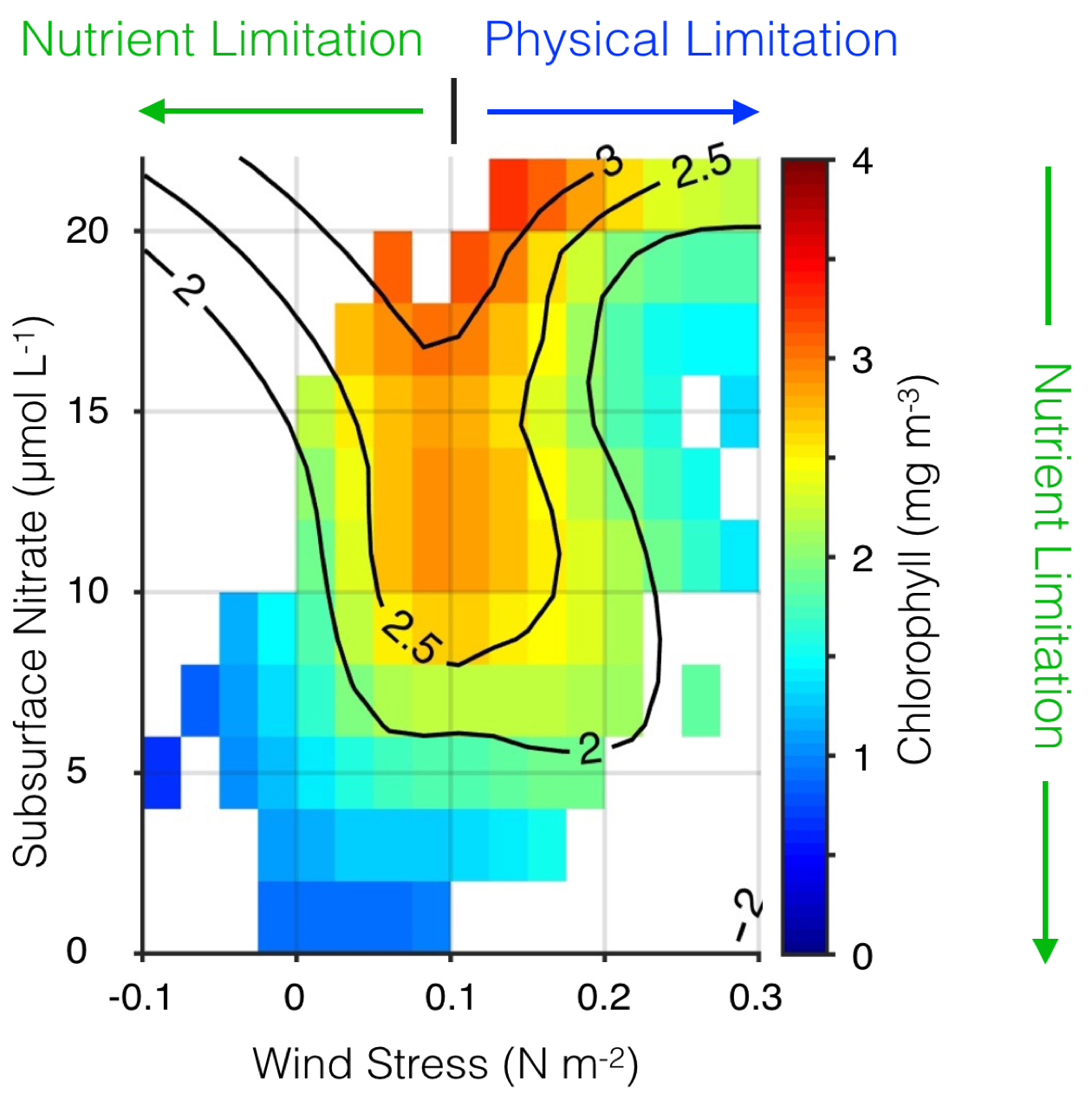

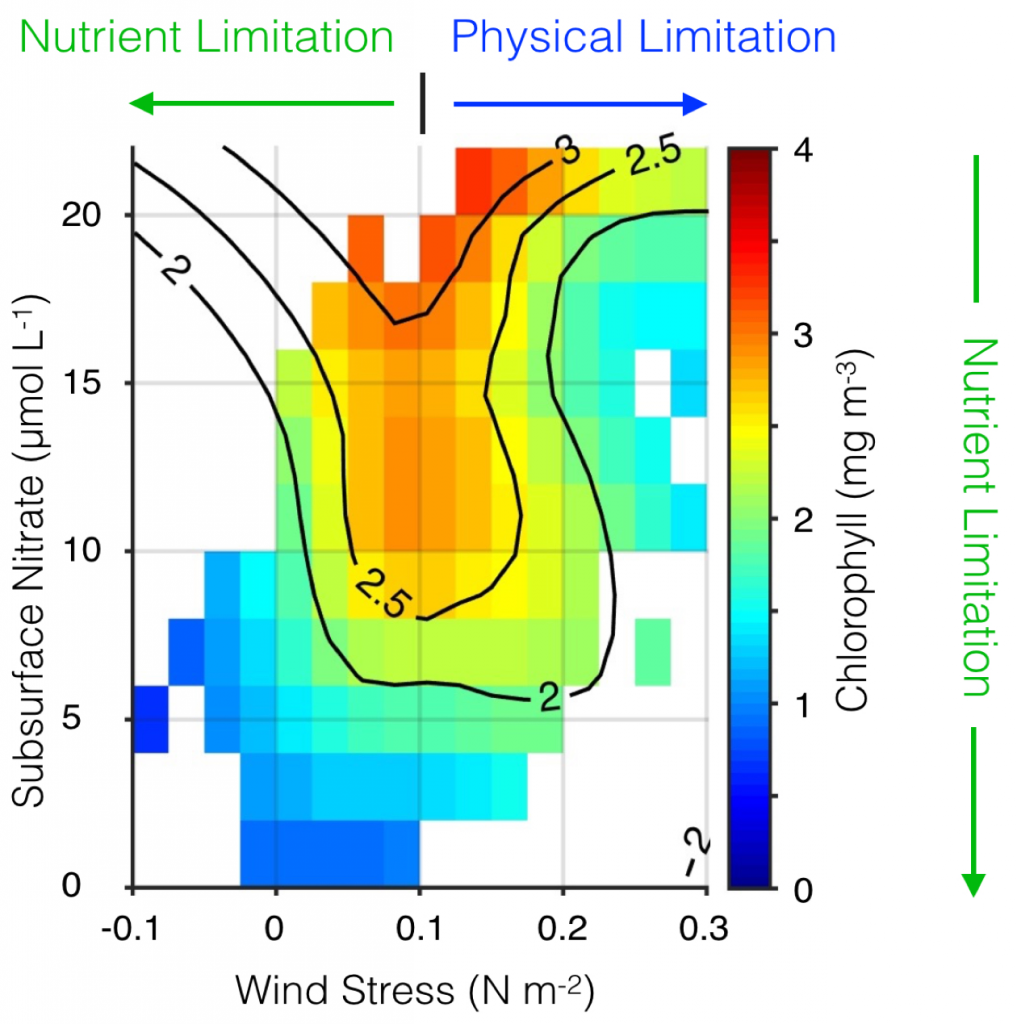

Southern Ocean biological productivity is instrumental in regulating the global carbon cycle. Previous correlative studies associated widespread mesoscale activity with anomalous chlorophyll levels. However, eddies simultaneously modify both the physical and biogeochemical environments via several competing pathways, making it difficult to discern which mechanisms are responsible for the observed biological anomalies within them. Two recently published papers track Southern Ocean eddies in a global, eddy-resolving, 3-D ocean simulation. By closely examining eddy-induced perturbations to phytoplankton populations, the authors are able to explicitly link eddies to co-located biological anomalies through an underlying mechanistic framework.

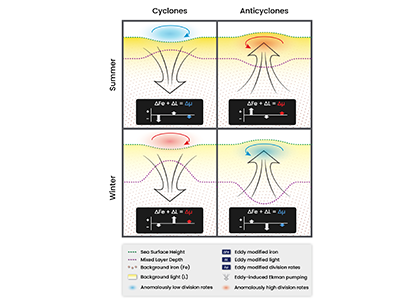

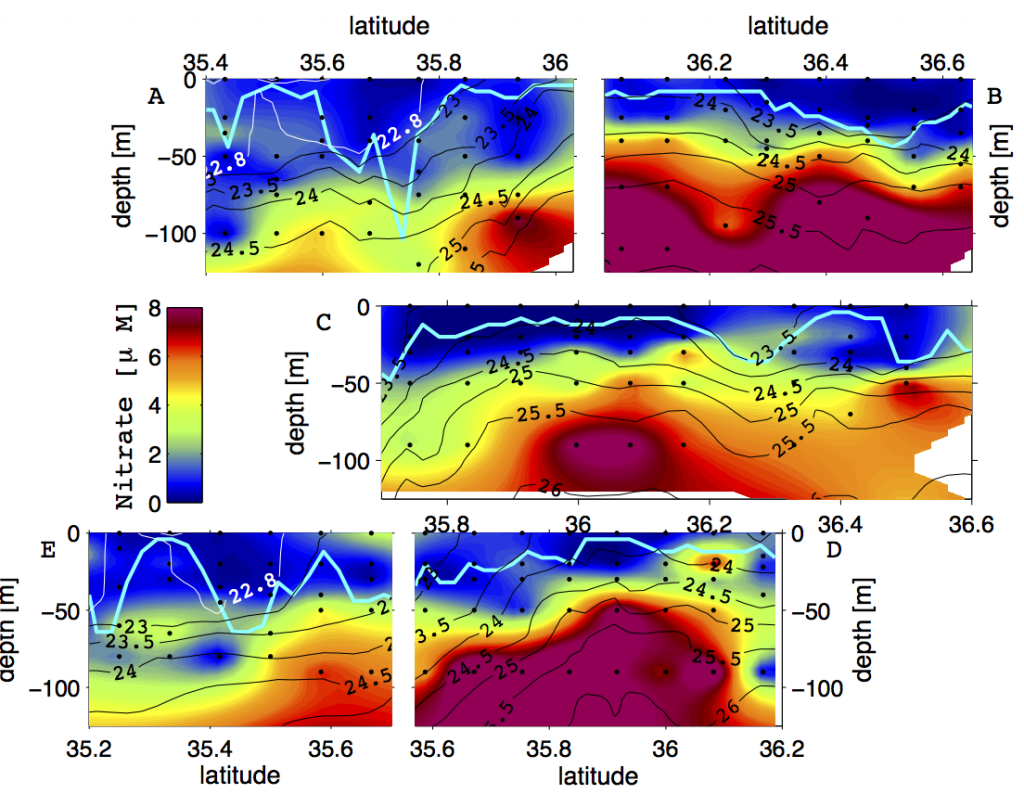

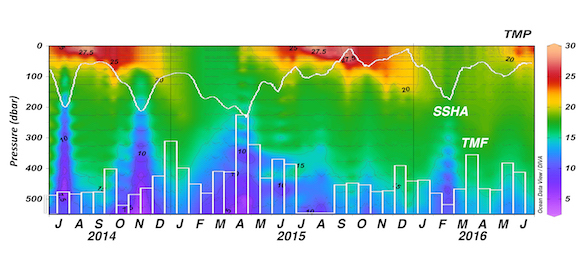

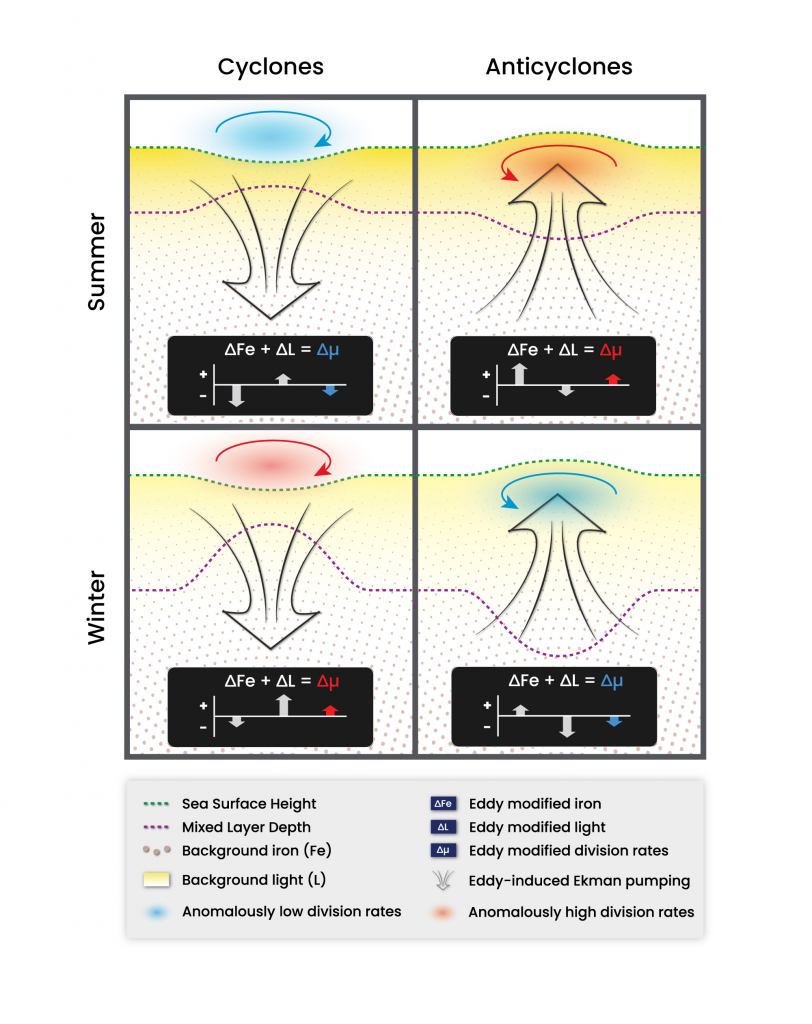

Figure caption: Simulated Southern Ocean eddies modify phytoplankton division rates in different directions of depending on the polarity of the eddy and background seasonal conditions. During summer anticyclones (top right panel) deliver extra iron from depth via eddy-induced Ekman pumping and fuel faster phytoplankton division rates. During winter (bottom right panel) the extra iron supply is eclipsed by deeper mixed layer depths and elevated light limitation resulting in slower division rates. The opposite occurs in cyclones.

In the first paper, the authors observe that eddies primarily affect phytoplankton division rates by modifying the supply of iron via eddy-induced Ekman pumping. This results in elevated iron and faster phytoplankton division rates in anticyclones throughout most of the year. However, during deep mixing winter periods, exacerbated light stress driven by anomalously deep mixing in anticyclones can dominate elevated iron and drive division rates down. The opposite response occurs in cyclones.

The second paper tracks how eddy-modified division rates combine with eddy-modified loss rates and physical transport to produce anomalous biomass accumulation. The biomass anomaly is highly variable, but can exhibit an intense seasonal cycle, in which cyclones and anticyclones consistently modify biomass in different directions. This cycle is most apparent in the South Pacific sector of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, a deep mixing region where the largest biomass anomalies are driven by biological mechanisms rather than lateral transport mechanisms such as eddy stirring or propagation.

It is important to remember that the correlation between chlorophyll and eddy activity observable from space can result from a variety of physical and biological mechanisms. Understanding the nuances of how these mechanisms change regionally and seasonally is integral in both scaling up local observations and parameterizing coarser, non-eddy resolving general circulation models with embedded biogeochemistry.

Authors:

Tyler Rohr (Australian Antarctic Partnership Program, previously at MIT/WHOI)

Cheryl Harrison (University of Texas Rio Grande Valley)

Matthew Long (National Center for Atmospheric Research)

Peter Gaube (University of Washington)

Scott Doney (University of Virginia)