Understanding decadal changes in the coastal carbonate system (CO2-system) is essential for predicting how the health of these waters is affected by anthropogenic drivers, such as changing atmospheric conditions and terrestrial inputs. However, studies that quantify the relative impacts of these drivers are lacking.

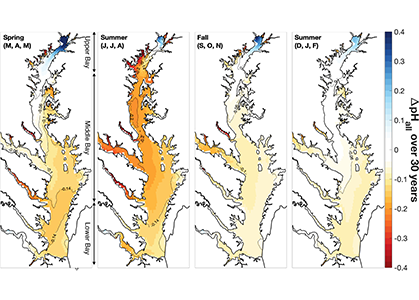

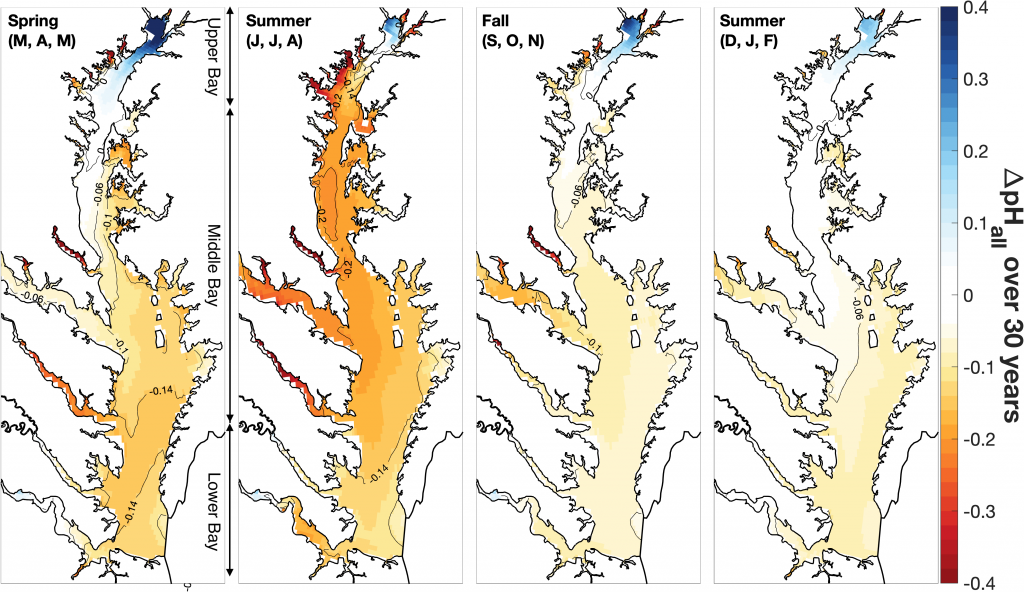

A recent study in Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans identified the primary drivers of acidification in the Chesapeake Bay over the past three decades. The authors used a three-dimensional hydrodynamic-biogeochemistry model to quantify the relative impacts on the Bay CO2-system from increases in atmospheric CO2, temperature, oceanic dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) concentrations, terrestrial loadings of total alkalinity (TA) and DIC, as well as decreases in terrestrial nutrient inputs. Decadal changes in the surface CO2-system in the Chesapeake Bay exhibit large spatial and seasonal variability due to the combination of influences from the land, ocean and atmosphere. In the upper Bay, increased riverine TA and DIC from the Susquehanna River have increased surface pH, with other drivers only contributing to decadal changes that are one to two orders of magnitude smaller. In the mid- and lower Bay, higher atmospheric CO2 concentrations and reduced nutrient loading are the two most critical drivers and have nearly equally reduced surface pH in the summer. These decadal changes in surface pH show significant seasonal variability with the greatest magnitude generally aligning with the spring and summer shellfish production season (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Overall changes in modeled surface pH (ΔpHall) due to all global and terrestrial drivers combined over the past 30 years (i.e., 2015–2019 relative to 1985–1989). ΔpHall includes changes in surface pH due to increased atmospheric CO2, increased atmospheric thermal forcing, increased oceanic dissolved inorganic carbon concentrations, decreased riverine nitrate concentrations, decreased riverine organic nitrogen concentrations, and increased riverine total alkalinity and dissolved inorganic carbon concentrations.

These results indicate that a number of global and terrestrial drivers play crucial roles in coastal acidification. The combined effects of the examined drivers suggest that calcifying organisms in coastal surface waters are likely facing faster decreasing rates of pH than those in open ocean ecosystems. Decreases in surface pH associated with nutrient reductions highlight that the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem is returning to a more natural condition, e.g., a condition when anthropogenic nutrient input from the watershed was lower. However, increased atmospheric CO2 is simultaneously accelerating the rate of change in pH, exerting increased stress on estuarine calcifying organisms. For ecosystems such as the Chesapeake Bay where nutrient loading is already being managed, controlling the emissions of anthropogenic CO2 globally becomes increasingly important to decelerate the rate of acidification and to relieve the stress on estuarine calcifying organisms. Future observational and modeling studies are needed to further investigate how the decadal trends in the Chesapeake Bay CO2-system may vary with depth. These efforts will improve our current understanding of long-term change in coastal carbonate systems and their impacts on the shellfish industry.

Authors:

Fei Da (Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary, USA)

Marjorie A. M. Friedrichs (Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary, USA)

Pierre St-Laurent (Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary, USA)

Elizabeth H. Shadwick (CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere, Australia)

Raymond G. Najjar (The Pennsylvania State University, USA)

Kyle E. Hinson (Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary, USA)