High-accuracy measurement of total alkalinity (TA) is crucial for our understanding of ocean acidification and the inorganic carbon complex. It is also particularly expensive in terms of labor and resources. These barriers limit its application in understudied settings such as inland waters and developing coastal regions.

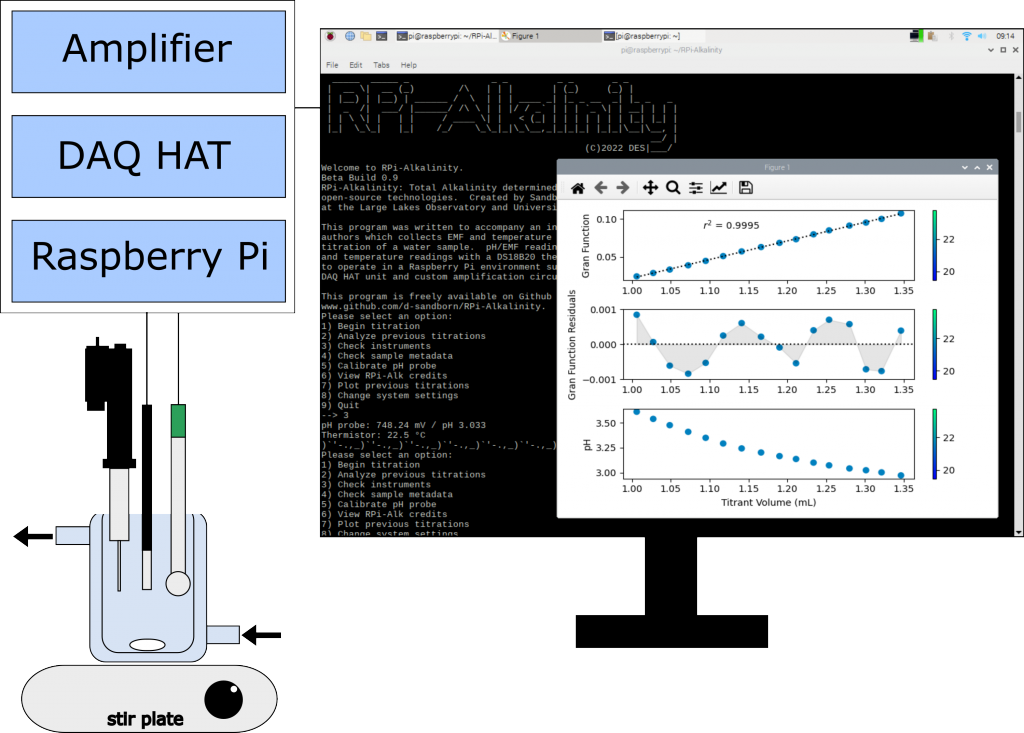

To address this problem, the authors constructed an instrument using open-source and low-cost principles and wrote about it in an article published in Limnology & Oceanography: Methods. The instrument implements a standard oceanographic open-cell acidimetric titration method within Python software written to coordinate titration, data acquisition, and calculation on a Raspberry Pi platform called RPiAlk. Repeated analysis of reference materials demonstrated TA measurement precision of 3.0 μmol/kg and measurement uncertainty of 5.3 μmol/kg. This uncertainty qualifies as “weather” level uncertainty (GOA-ON 2015) and approaches “climate” level uncertainty.

We hope the accessibility of this design will aid its replication and improvement by other alkalinity-measuring laboratories, including researchers, regulators, and educators previously without access to such TA instrumentation. An expanded production of high-quality TA measurements may aid scientific understanding of understudied waters around the world.

Authors

Daniel Sandborn (University of Minnesota, Saint Paul)

Elizabeth Minor (University of Minnesota Duluth)

Craig Hill (University of Minnesota Duluth)

Mastodon: @DanielSandborn@sciencemastodon.com

Twitter: @DanielSandborn | @CraigHill_UMD

Backstory

RPiAlk came about as an artifact of instrument development in the Minor Lab at the Large Lakes Observatory. The author had been growing weary of the poor measurement repeatability of manual Gran titration (common in inland waters) and the many problems with comparison to non-linear titration curve fitting demonstrated in Dickson’s SOPs, so he decided to write a program to automate it. To the author’s delight, Dr. M. Humphreys had already written a fantastic TA calculation program, Calkulate. All that was needed was a simple wrapper and I/O function, right? Not quite. If only software and instrument development was that easy. Debugging became as tiresome as it was rewarding and educational.