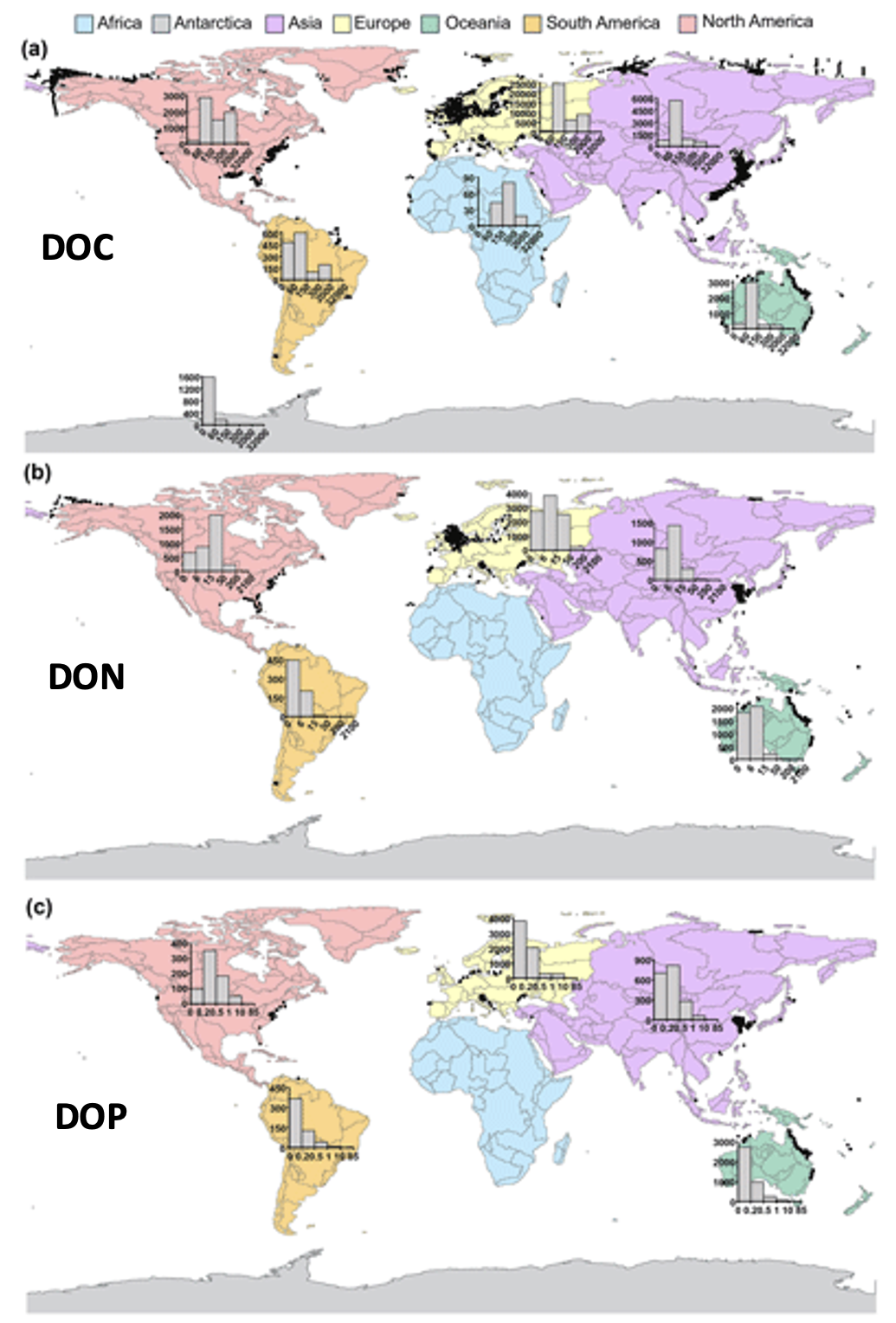

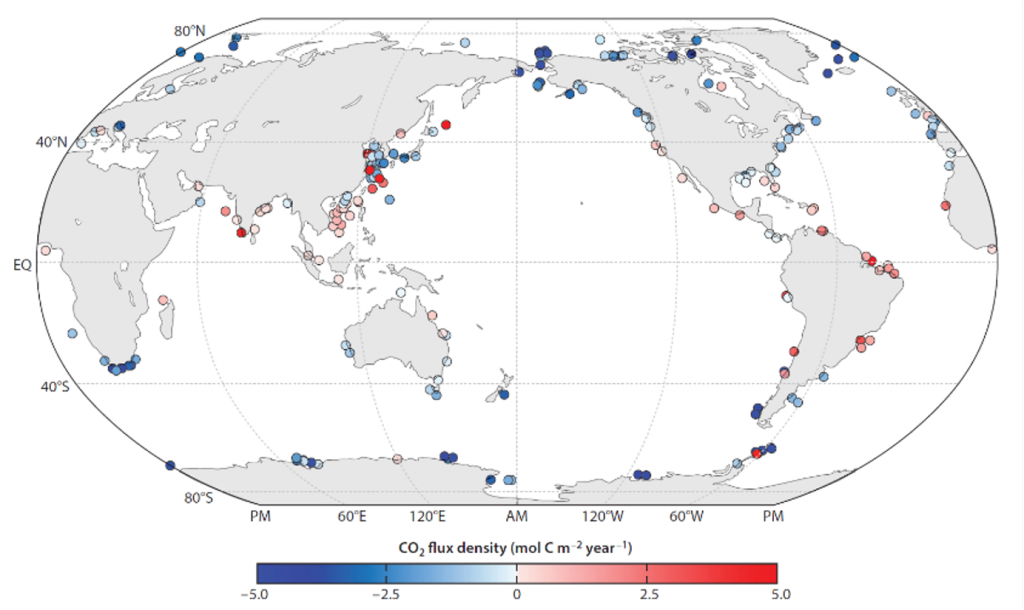

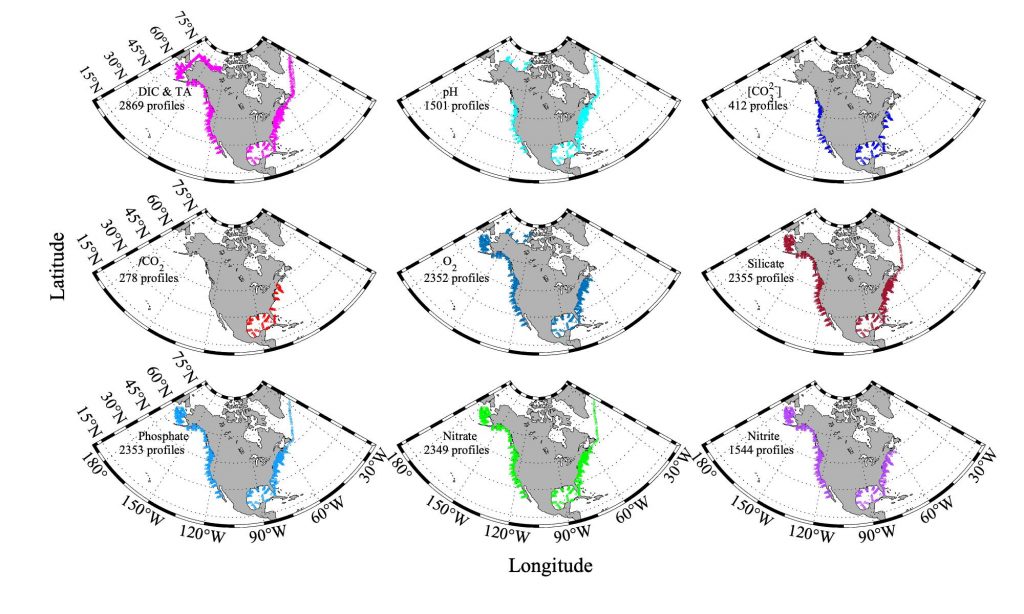

We present the first edition of a global database (CoastDOM v1) and a resulting data manuscript, which compiles previously published and unpublished measurements of DOC, DON, and DOP in coastal waters, consisting of 62,338 (DOC), 20,356 (DON), and 13,533 (DOP) data points, respectively.

CoastDOM v1 includes observations of concentrations from all continents between 1978 and 2022. However, most data were collected in the Northern Hemisphere, with a clear gap in DOM measurements from the Southern Hemisphere.

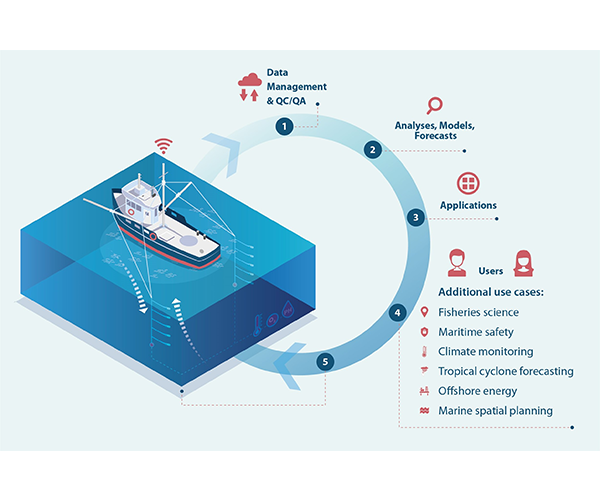

This dataset will be useful for identifying global spatial and temporal patterns in DOM and will help facilitate the reuse of DOC, DON, and DOP data in studies aimed at better characterizing local biogeochemical processes; closing nutrient budgets; estimating carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorous pools; and establishing a baseline for modelling future changes in coastal waters.

The aim is to publish an updated version of the database periodically to determine global trends of DOM levels in coastal waters, and so if you have DOM data lying around, please submit it to Christian Lønborg (c.lonborg@ecos.au.dk).

CITATIONS

Lønborg et al. 2024. A global database of dissolved organic matter (DOM) concentration measurements in coastal waters (CoastDOM v1), Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 16, 1107–1119, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-16-1107-2024

Lønborg et al. 2023.A global database of dissolved organic matter (DOM) concentration measurements in coastal waters (CoastDOM v.1). PANGAEA, https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.964012