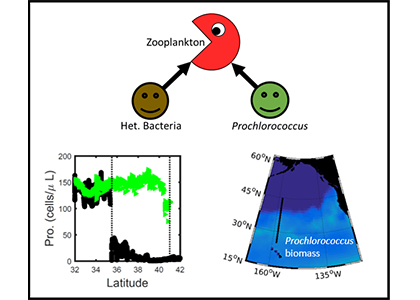

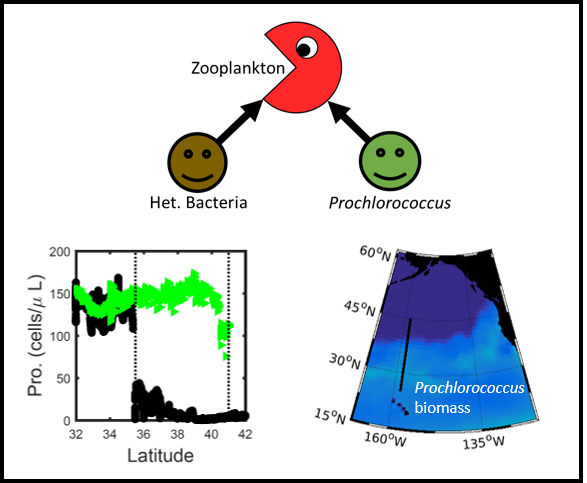

Prochlorococcus is the world’s smallest phytoplankton (microscopic plant-like organisms) and the most numerous, with more than ten septillion individuals. This tiny plankton lives ubiquitously in warm, blue, tropical waters but is conspicuously absent in more polar regions. The prevailing theory was the cold: Prochlorococcus doesn’t grow at low temperatures. In a recent paper, the authors argue ecological control, in particular, predation by zooplankton. Cold polar waters are greener because they contain more nutrients, leading to more life and more organic matter production. This production feeds more and larger heterotrophic bacteria, who then feed larger predators—specifically the same zooplankton that consume Prochlorococcus. If the shared zooplankton increases enough, it will consume Prochlorococus faster than it can grow, causing the species to collapse at higher latitudes. These results show that an understanding of both ecology and temperature is required to predict how these ecosystems will shift in a warming ocean.

Figure 1: Surface populations of Prochlorococcus collapse (dashed lines) moving northward from Hawaii as seen in transects (transect line shown in red on map, lower left) from cruises in April 2016 (black dots) and September 2017 (green triangles). This collapse of the Prochlorococcus emerges in dynamical computer models (lower right, color indicates Prochlorococcus biomass in mgC/m3) when heterotrophic bacteria and Prochlorococcus share a grazer (top schematic). Increased organic production heading poleward first increases the heterotrophic bacterial population, increasing the shared zooplankton population which eventually consumes Prochlorococcus faster than it can grow (dashed contour).

Authors

Christopher L. Follett (MIT)

Stephanie Dutkiewicz (MIT)

François Ribalet (UW)

Emily Zakem (USC)

David Caron (USC)

E. Virginia Armbrust (UW)

Michael J. Follows (MIT)