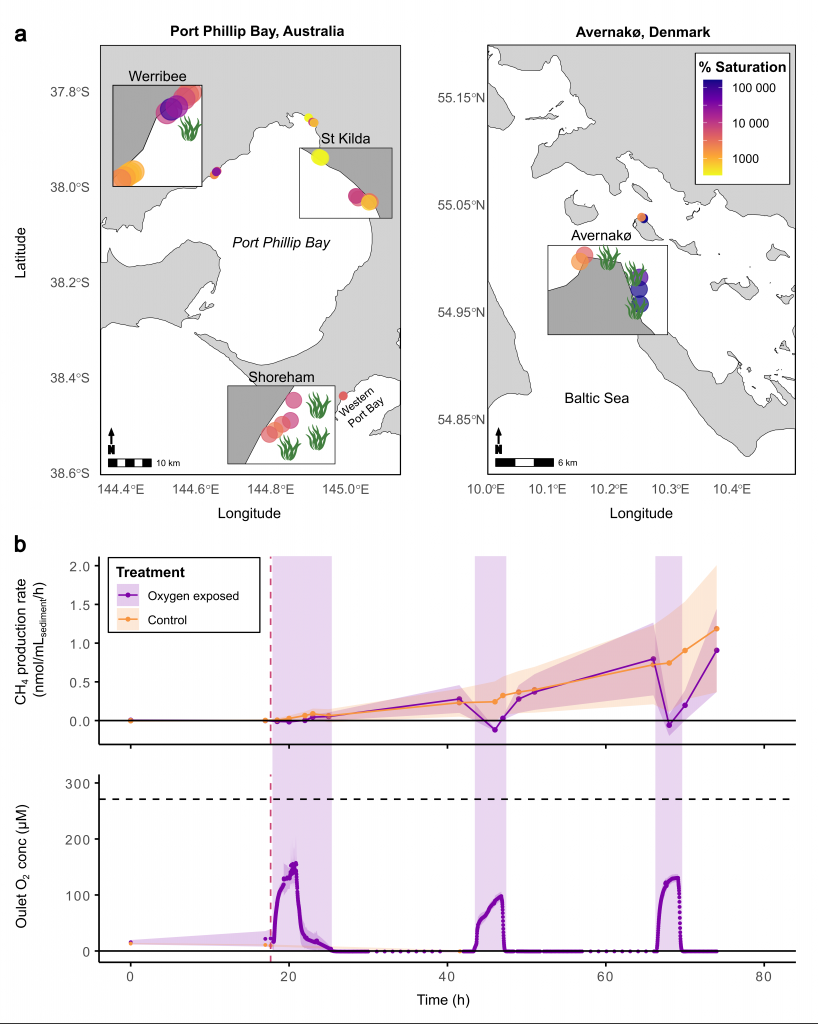

A recent study in Nature Geosciences observed high concentrations of methane overlying permeable (sand) sand sediments in bays in Denmark and Australia. These environments are not one would expect to see methane because they are highly oxygenated and the high concentrations of sulfate in seawater typically inhibit methanogenesis. The authors showed that the methane was not being imported from local groundwater using geochemical methods. Using a combination of biogeochemical, microbial isolation, culturing and genomic approaches, revealed that methane was being produced by fast growing microbes resistant to oxygen exposure using plant produced substrates such as dimethylsulfide and amines. This work shows that where marine plants such as seaweed and seagrass grow and accumulate there may be high and sporadic production of methane. This has implications for how we account for the carbon sequestering capacity of coastal environments and the climate impact of increasing algal blooms such as coastal Ulva and the great sargassum bloom.

Authors

Perran Cook (Monash University)

Ning Hall (University of free spirit)