Picophytoplankton, the smallest phytoplankton on Earth, are dominant in over half of the global surface ocean, growing in low-nutrient “ocean deserts” where diatoms and other large phytoplankton have difficult to thrive. Despite their small size, picophytoplankton collectively account for well over 50% of primary production in oligotrophic waters, thus playing a major role in sustaining marine food webs.

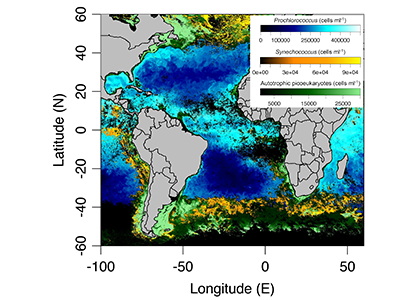

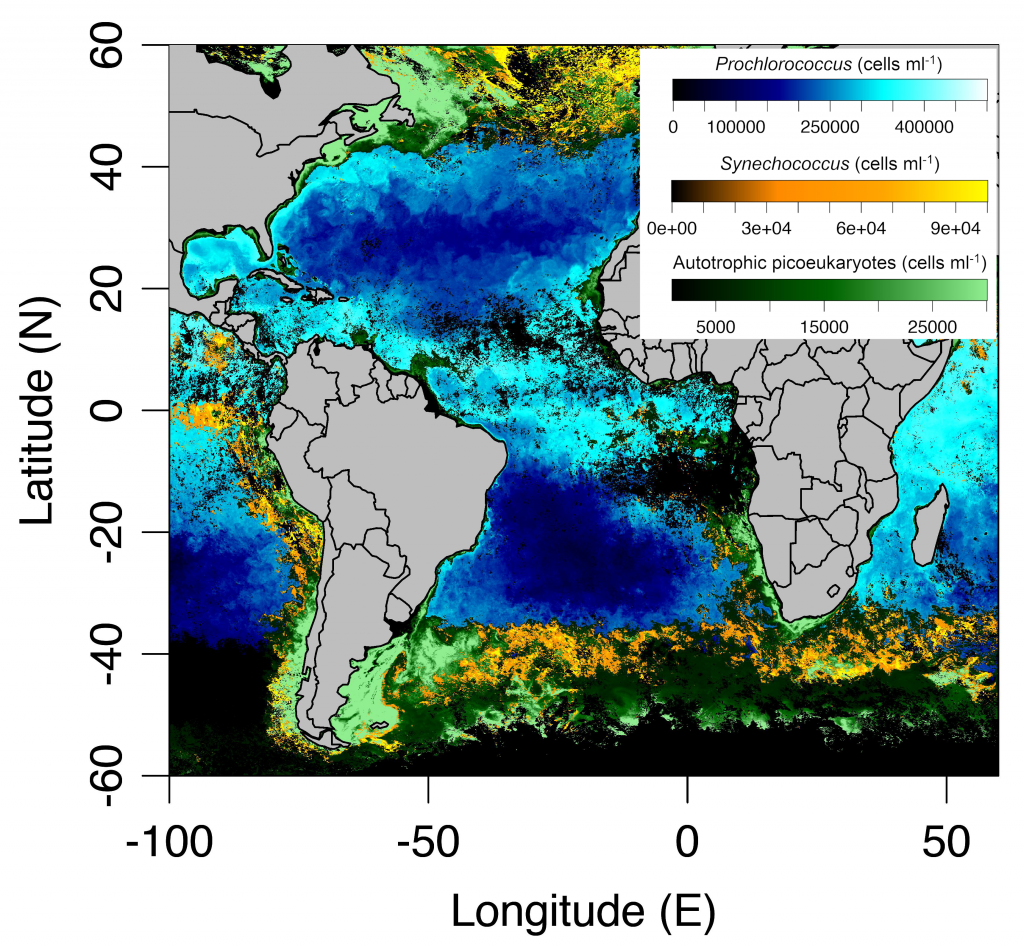

In a recent paper published in Optics Express, the authors use satellite-detected ocean color (namely remote-sensing reflectance, Rrs(λ)) and sea surface temperature to estimate the abundance of the three picophytoplankton groups—the cyanobacteria Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus, and autotrophic picoeukaryotes. The authors analysed Rrs(λ) spectra using principal component analysis, and principal component scores and SST were used in the predictive models. Then, they trained and independently evaluated the models with in-situ data from the Atlantic Ocean (Atlantic Meridional Transect cruises). This approach allows for the satellite detection of the succession of species across ocean oligotrophic ecosystem boundaries, where these cells are most abundant (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cell abundances of the three major picophytoplankton groups (the cyanobacteria Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus, and a collective group of autotrophic picoeukaryotes) in surface waters of the Atlantic Ocean. Abundances are shown for the dominant group in terms of total biovolume (converted from cell abundance).

Since these organisms can be used as proxies for marine ecosystem boundaries, this method can be used in studies of climate and ecosystem change, as it allows a synoptic observation of changes in picophytoplankton distributions over time and space. For exploring spectral features in hyperspectral Rrs(λ) data, the implementation of this model using data from future hyperspectral satellite instruments such as NASA PACE’s Ocean Color Instrument (OCI) will extend our knowledge about the distribution of these ecologically relevant phytoplankton taxa. These observations are crucial for broad comprehension of the effects of climate change in the expansion or shifts in ocean ecosystems.

Authors:

Priscila K. Lange (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center / Universities Space Research Association / Blue Marble Space Institute of Science)

Jeremy Werdell (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center)

Zachary K. Erickson (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center)

Giorgio Dall’Olmo (Plymouth Marine Laboratory)

Robert J. W. Brewin (University of Exeter)

Mikhail V. Zubkov (Scottish Association for Marine Science)

Glen A. Tarran (Plymouth Marine Laboratory)

Heather A. Bouman (University of Oxford)

Wayne H. Slade (Sequoia Scientific, Inc)

Susanne E. Craig (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center / Universities Space Research Association)

Nicole J. Poulton (Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences)

Astrid Bracher (Alfred-Wegener-Institute Helmholtz Center for Polar and Marine Research / University of Bremen)

Michael W. Lomas (Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences)

Ivona Cetinić (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center / Universities Space Research Association)