Although chlorophyll fluorescence is widely-used as a proxy for chlorophyll concentration, sunlight exposure makes fluorescence measurements inaccurate through a process called non-photochemical quenching, limiting its proxy accuracy during daylight hours. In the open ocean, where time and space scales are large relative to variability in phytoplankton concentration, daytime chlorophyll fluorescence—necessary for satellite algorithm validation and for understanding diurnal variability in phytoplankton abundance—can be estimated by averaging across successive nighttime, unquenched values. In coastal waters, where semidiurnal tidal advection drives small scale patchiness and short temporal variability, successive nighttime observations do not accurately represent the intervening daytime. Thus, it is necessary to apply a non-photochemical quenching correction that accounts for the additional effect of tidal advection.

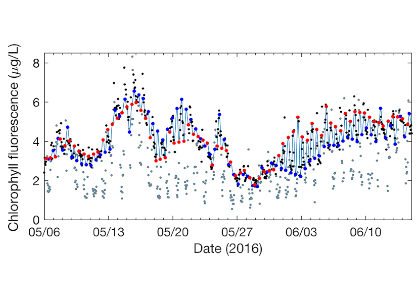

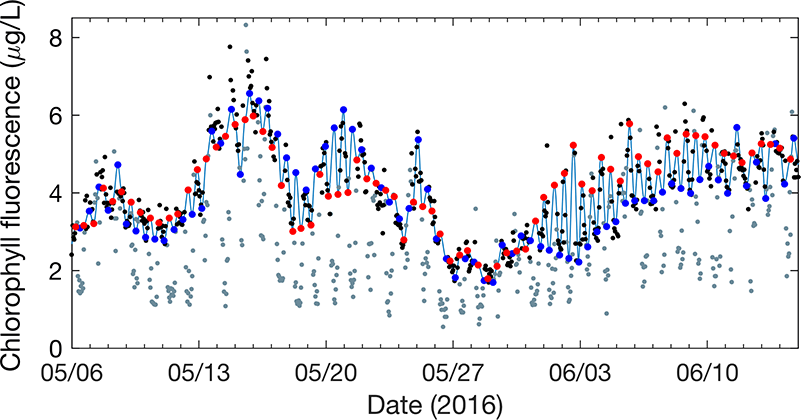

In a recent study in L&O Methods, authors developed a model that uses measurements of tidal velocity to correct daytime chlorophyll fluorescence for non-photochemical quenching and tidal advection. The model identifies high tide and low tide endmember populations of phytoplankton from tidal velocity, and estimates daytime chlorophyll fluorescence as a conservative interpolation between endmember fluorescence at those tidal maxima and minima (Figure 1). Rather than removing nearly 12 hours’ worth of hourly chlorophyll fluorescence observations (i.e., all of the daytime observations) as was previously necessary, this model recovers them. The model output performs more accurately as a proxy for chlorophyll concentration than raw daytime chlorophyll fluorescence measurements by a factor of two, and enables tracking of phytoplankton populations with chlorophyll fluorescence in a Lagrangian sense from Eulerian measurements. Finally, because the model assumes conservation, periods of non-conservative variability are revealed by comparison between model and measurements, helping to elucidate controls on variability in phytoplankton abundance in coastal waters.

Figure 1: Model (light blue line) is a tidal interpolation between high tide (blue points) and low tide (red points) phytoplankton endmembers. The model represents nighttime, unquenched chlorophyll fluorescence measurements well (black points), while daytime, quenched measurements are visibly reduced (gray points).

This result is a critical achievement, as it enables the use of daytime chlorophyll fluorescence, which increases the temporal resolution of coastal chlorophyll fluorescence measurements, and also provides a mechanism for satellite validation of the ocean color chlorophyll data product in coastal waters. The model’s capacity to accurately simulate the pervasive effect of non-photochemical quenching makes it a vital tool for any researcher or coastal water manager measuring chlorophyll fluorescence. This model will help to provide new insights on the movement of and controls on phytoplankton populations across the land-ocean continuum.

Authors:

Luke Carberry (University of California, Santa Barbara)

Collin Roesler (Bowdoin College)

Susan Drapeau (Bowdoin College)