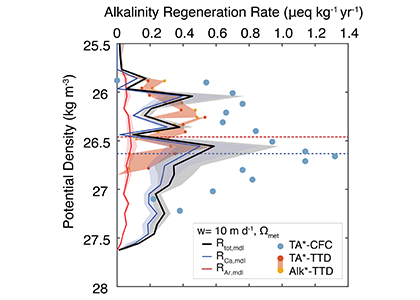

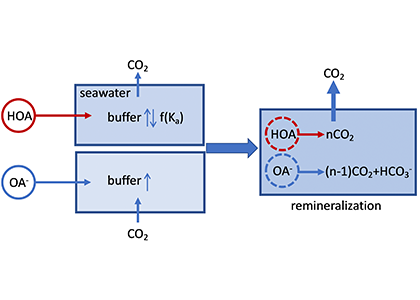

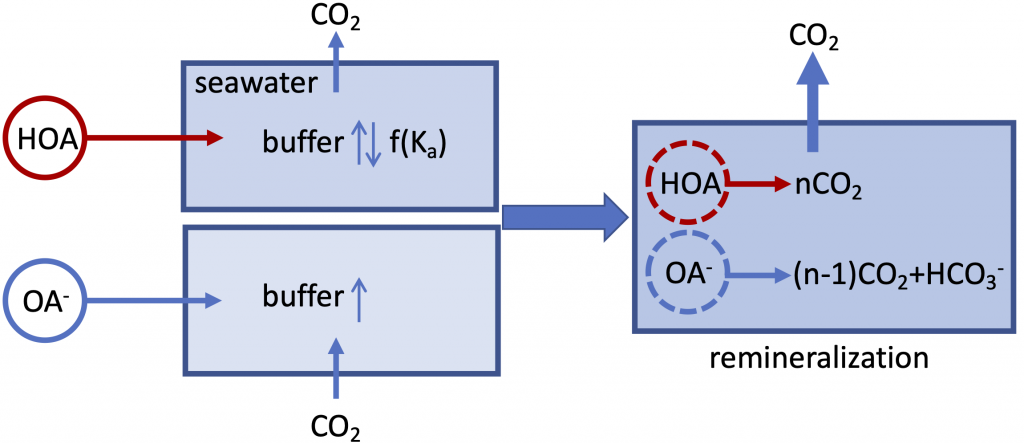

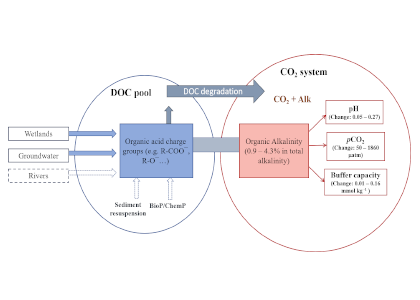

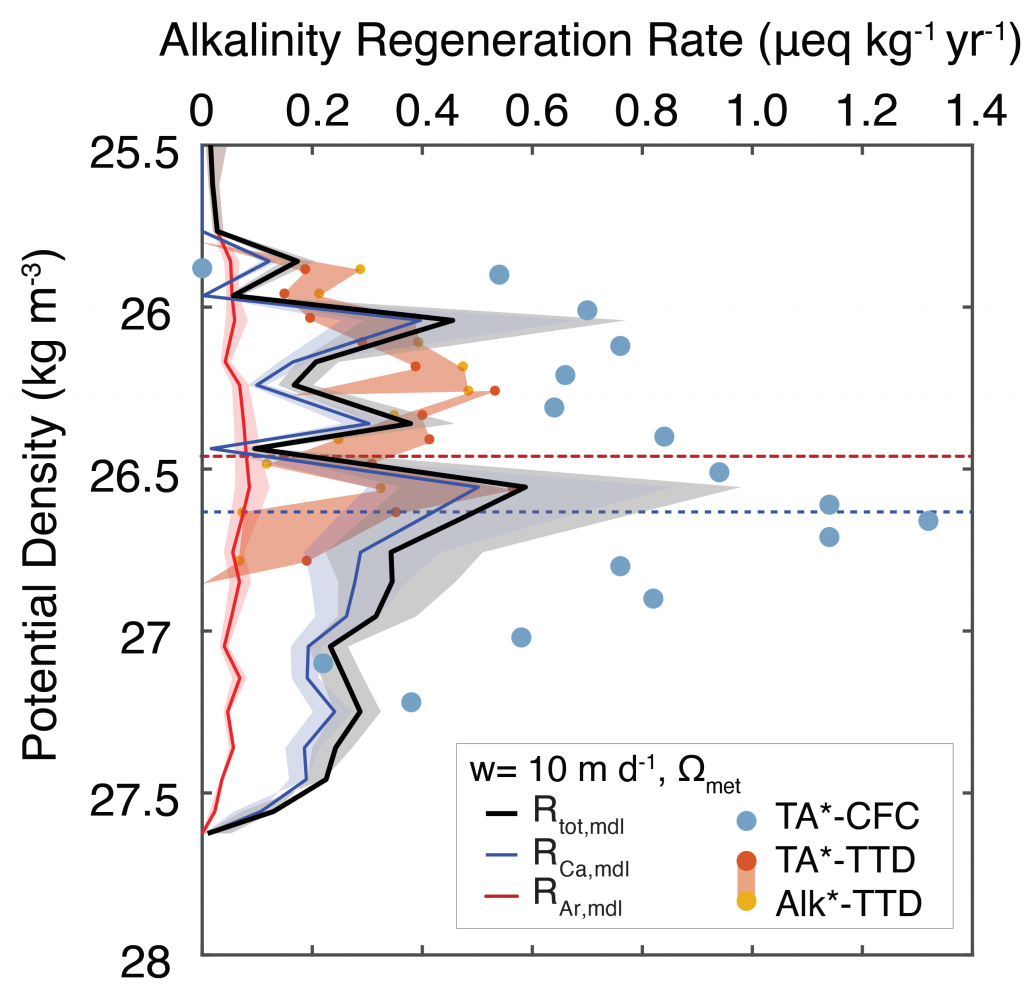

The marine carbon and alkalinity cycles are tightly coupled. Seawater stores so much carbon because of its high alkalinity, or buffering capacity, and the main driver of alkalinity cycling is the formation and dissolution of biologically produced calcium carbonate (CaCO3). In a recent publication in GBC, the authors conducted novel carbon-13 tracer experiments to measure the dissolution rates of biologically produced CaCO3 along a transect in the North Pacific Ocean. They combined these experiment data with shipboard analyses of the dissolved carbonate system, the 13C-content of dissolved inorganic carbon, and CaCO3 fluxes, to constrain the alkalinity cycle in the upper 1000 meters of the water column. Dissolution rates were too slow to explain alkalinity production or CaCO3 loss from the particulate phase. However, driving dissolution with the metabolic consumption of oxygen brings alkalinity production and CaCO3 loss estimates into quantitative agreement (Figure). The authors argue that a majority of CaCO3 production is likely dissolved through metabolic processes in the upper ocean, including zooplankton grazing, digestion, and egestion, and microbial degradation of marine particle aggregates that contain both organic carbon and CaCO3. This hypothesis stems from the basic fact that almost all marine CaCO3 is biologically produced, placing CaCO3 at the source of the acidifying process (metabolic consumption of organic matter). This process is important because it puts an emphasis on biological processing for the cycling of not only carbon, but also alkalinity, the main buffering component in seawater. These results should help both scientists and stakeholders to understand the fundamental controls on calcium carbonate cycling in the ocean, and therefore the processes that distribute alkalinity throughout the world’s oceans.

Figure Caption: Sinking-dissolution model results compared with tracer-based alkalinity regeneration rates (TA*-CFC, Feely et al., 2002). We also plot alkalinity regeneration rates using updated time transit distribution ages (TA*- and Alk*-TTD). The modeled alkalinity regeneration rate uses our measured dissolution rates for biologically produced calcite and aragonite, and is driven by a combination of background saturation state and metabolic oxygen consumption. The dissolution rate is split up into a calcite component (produced mainly by coccolithophores) and an aragonite component (produced mainly by pteropods). Aragonite does not contribute significantly to the overall dissolution rate. Driving dissolution by metabolic oxygen consumption produces alkalinity regeneration rates that are in quantitative agreement with tracer-based estimates.

Authors:

Adam Subhas (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) et al.

Also see Eos highlight here