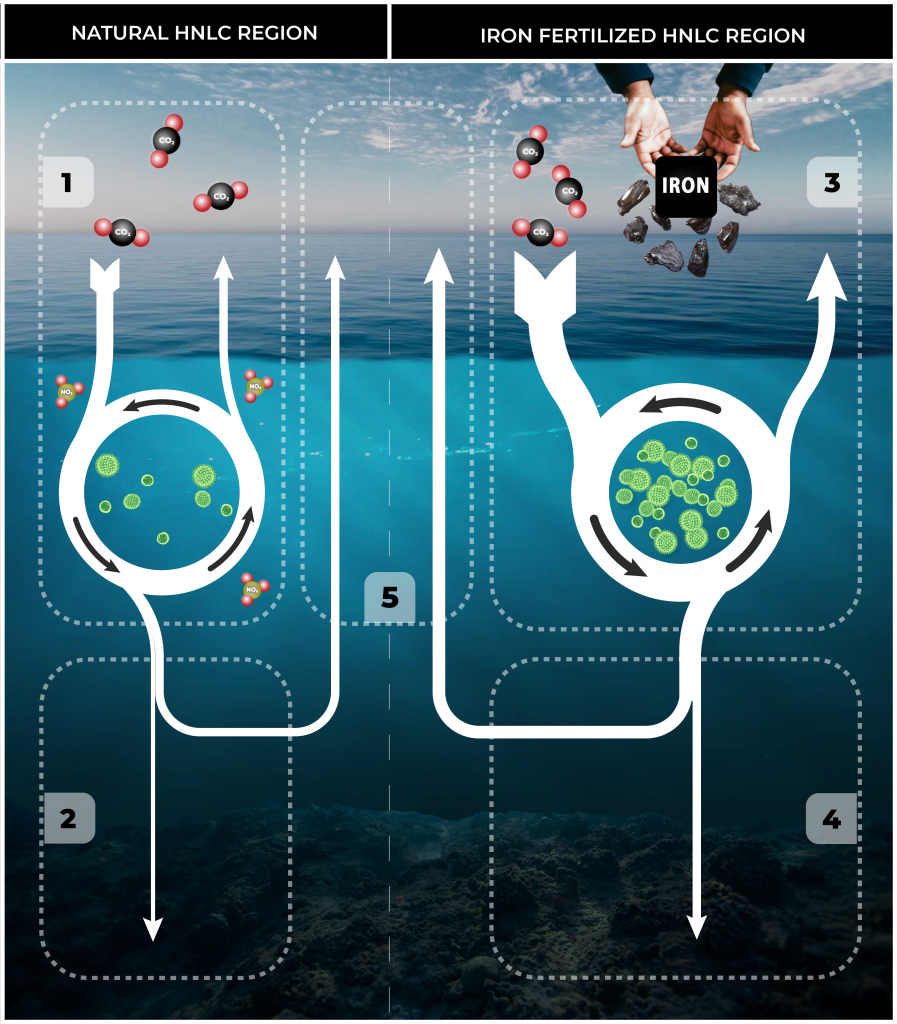

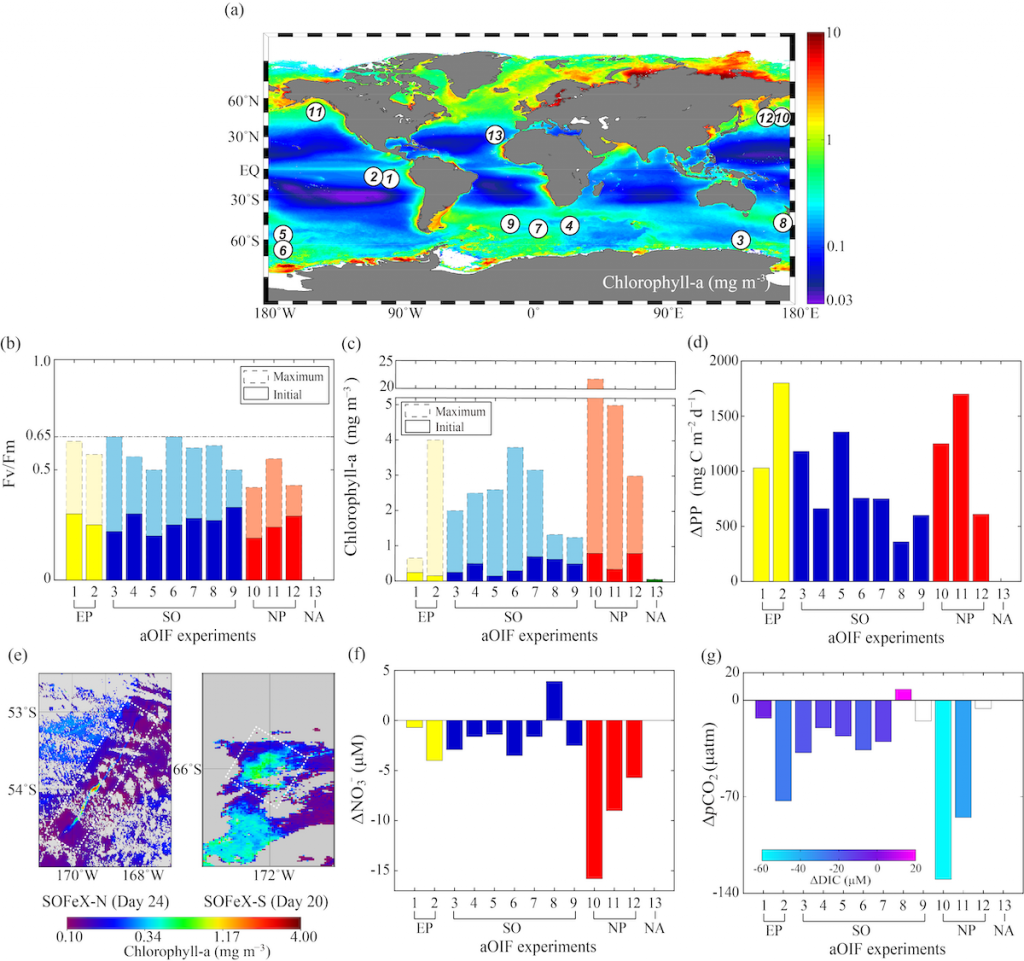

Amidst a heightened focus on the need for both drastic and immediate emissions reductions and carbon dioxide removal to limit warming to 1.5°C (IPCC, 2022), attention is returning to ocean iron fertilization (OIF) as a means of marine carbon dioxide removal (mCDR). First discussed in the early 1990s by John Martin, the concept posits that fertilization of iron-limited marine phytoplankton would lead to enhanced ocean carbon storage via a stimulation of the ocean’s biological carbon pump. However, we lack knowledge about how OIF might operate in concert with an ocean responding to climate change and what the consequences of altered nutrient consumption patterns might be for marine ecosystems, particularly for fisheries in national exclusive economic zones (EEZs). Tagliabue et al. (2023) addressed this in a recent study using state-of-the-art climate, ocean biogeochemical, and ecosystem models under a high-emissions scenario.

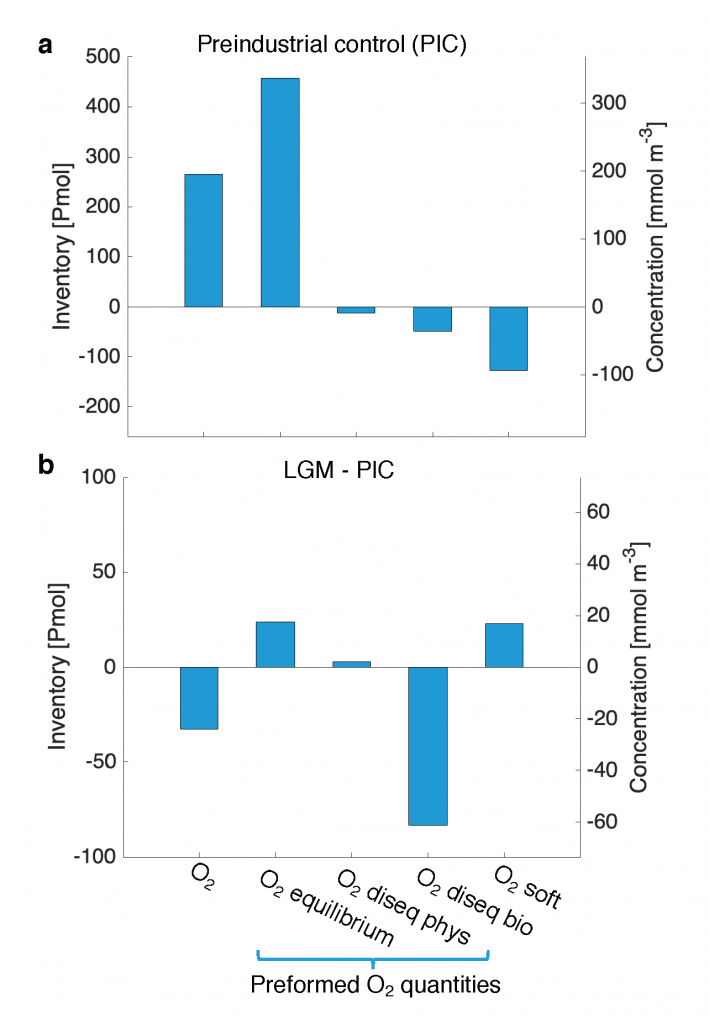

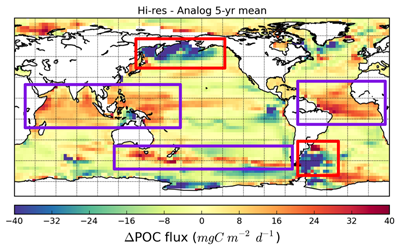

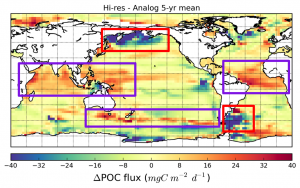

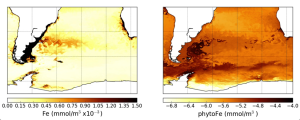

The study’s findings suggested that OIF can contribute at most a few 10s of Pg of mCDR under a high-emissions climate change scenario. This is equivalent to fewer than five years of current emissions and is consistent with earlier modeling assessments. This estimate is based on the modeled representation of carbon and iron cycling and a highly efficient OIF strategy that may be difficult to achieve in practice. Enhanced surface uptake of major nutrients due to OIF also led to a drop in global net primary production, in addition to that due to climate change alone. By then coupling a complex model of upper trophic levels, the projected declines in animal biomass due to climate change were amplified by around a third due to OIF, with the most negative impacts projected to occur in the low latitude EEZs, which are already facing increasing pressures due to climate change.

This work highlights feedbacks within the ocean’s biogeochemical and ecological systems in response to OIF that emerged over large spatial and temporal scales. Associated pressures on marine ecosystems pose major challenges for proposed management and monitoring. Restricting OIF to the highest latitudes of the Southern Ocean might mitigate some of these negative effects, but this only further reduces the minor mCDR benefit, suggesting that OIF may not make a significant contribution.

Authors

A. Tagliabue (Univ. Liverpool)

B. S. Twining (Bigelow Laboratory)

N. Barrier & O. Maury (MARBEC, IRD, IFREMER, CNRS, Université de Montpellier, France)

M. Berger & Laurent Bopp (ENS-LMD, Paris, France)

IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. in Climate Change, 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds. Shukla, P. R. et al.) (Cambridge University Press, 2022).