How deep in the ocean do microbes feel the effects of nutrient limitation? Microbial production in one third of the surface ocean is limited by the essential micronutrient iron (Fe). This limitation extends to at least the bottom of the euphotic zone, but what happens below that?

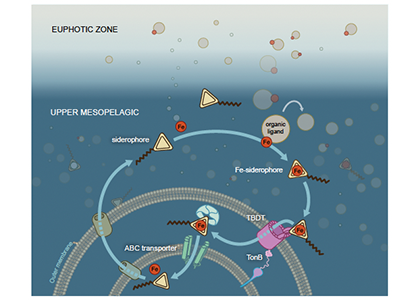

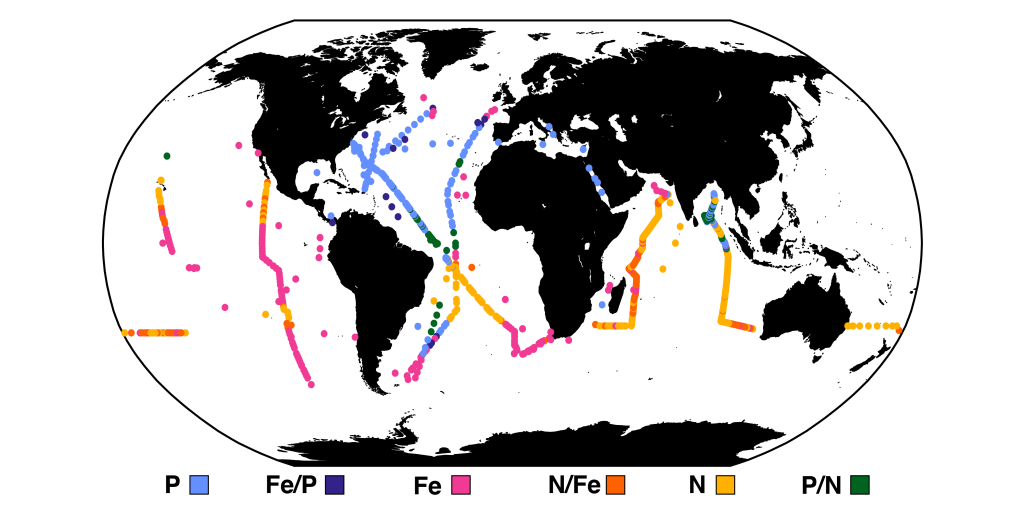

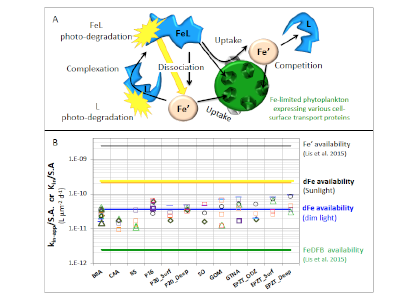

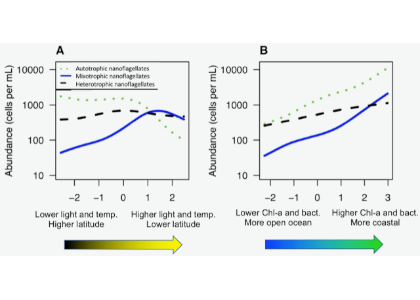

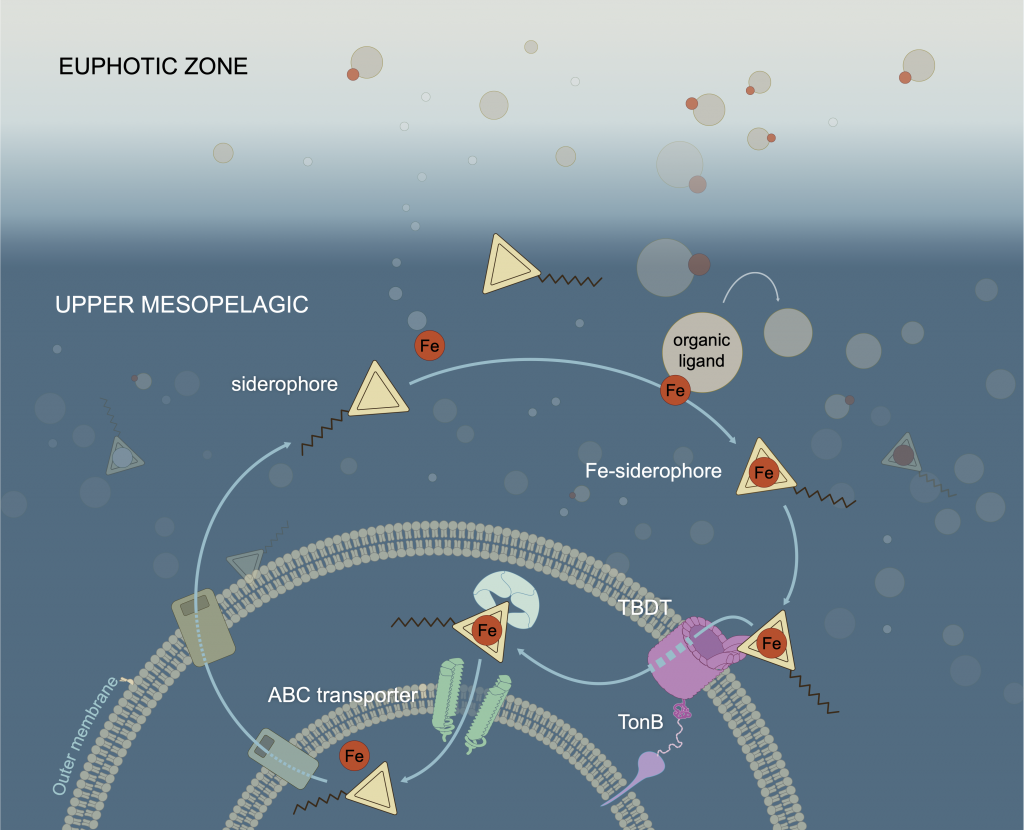

In a study that recently published in Nature we investigated the abundance and distribution of siderophores, small metabolites synthesized by bacteria to promote Fe uptake. When environmental Fe concentrations become limiting and microbes become Fe deficient, some bacteria release siderophores into the environment to bind iron and facilitate its uptake. Siderophores are therefore a window into how microbes “see” environmental Fe. We found that siderophore concentrations were high in low Fe surface waters, but surprisingly we also found siderophores to be abundant in the twilight zone (200-500 m) underlying the North and South Pacific subtropical gyres, two key ecosystems for the marine carbon cycle. In shipboard experiments with siderophores labeled with the rare 57Fe isotope, we found rapid uptake of the label in twilight zone samples. After removing 57Fe from the 57Fe-siderophores complex, bacteria released the now unlabeled siderophores back into seawater to complex additional Fe (Figure. 1).

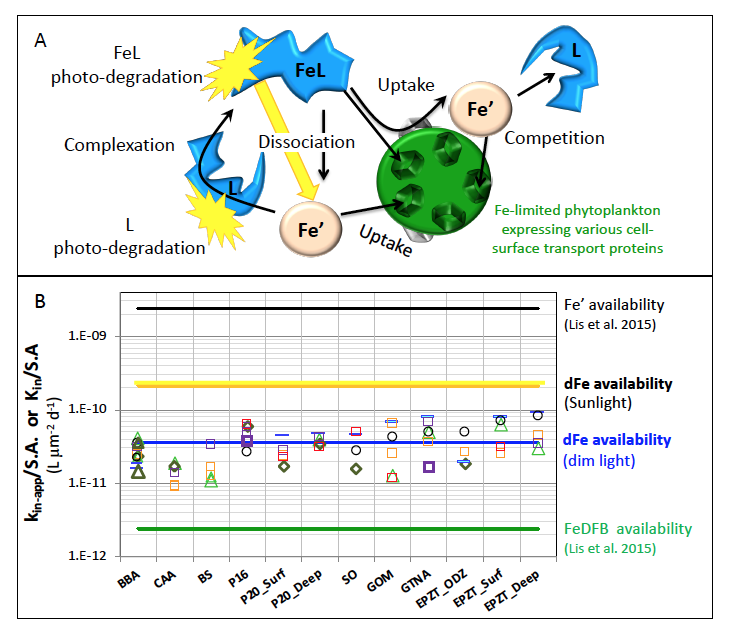

Figure 1: Iron-siderophore cycling in the twilight zone. When the seawater becomes Fe-deficient, some bacteria are able to synthesize siderophores and release them into the environment (middle left). These metabolites bind Fe (middle right) and the Fe-siderophore complex is taken up by bacteria using specialized TonB dependent transporters (TBDT; bottom right). Inside the cell, Fe is recovered from the Fe-siderophore complex (bottom left) and the siderophore excreted back into the environment to start the cycle anew.

Our results show that in large parts of the ocean microbes feel the effects of nutrient limitation deep in the water column, to at least 500 m. This greatly expands the region of the ocean where nutrients limit microbial metabolism. The effects of limitation this deep in the water column are unexplored, but twilight zone Fe deficiency could have unanticipated consequences for the efficiency of the ocean’s biological carbon pump.

Authors

Jingxuan Li, Lydia Babcock-Adams and Daniel Repeta

(all at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)