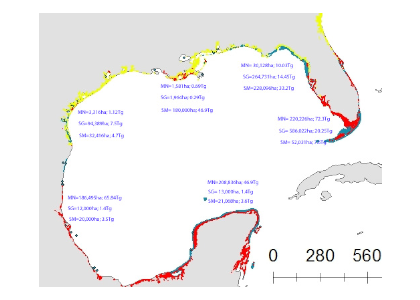

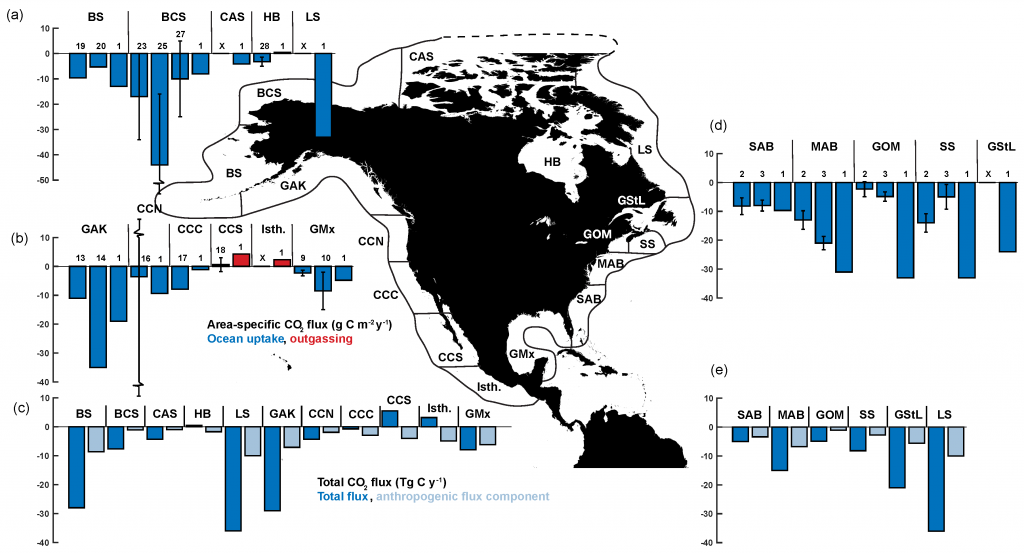

Carbon fluxes in the coastal ocean and across its boundaries with the atmosphere, land, and the open ocean are an important but poorly constrained component of the global carbon budget. By synthesizing available observations and model simulations, a recent study aims to answer 1) whether the coastal ocean of North America takes up atmospheric CO2 and exports carbon to the open ocean; and 2) if so, how much? The authors estimate a net carbon sink of 160±80 Tg C yr−1 in the North American Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) with the Arctic, sub-Arctic and mid-latitude Atlantic EEZ regions as the major contributors.

| Portion of EEZ | Tg C yr−1 | % of the total area |

| Arctic and sub-Arctic | 104 | 51% |

| Mid-latitude Atlantic | 62 | 25% |

| Mid-latitude Pacific | -3.7 | 24% |

Table 1: Regional breakdown of estimated carbon sink in the North Atlantic EEZ (negative values imply a carbon source).

Combining the net uptake with an estimate of carbon input from land of minus estimates of burial and accumulation of dissolved carbon in EEZ waters as follows implies a carbon export of 151±105 Tg C yr−1 to the open ocean.

|

160±80 Tg C yr−1 |

+ |

106±30 Tg C yr−1 |

– |

65±55 Tg C yr−1 |

– |

50±25 Tg C yr−1 |

= |

151±105 Tg C yr−1 |

|

Net uptake

|

Carbon input from land | Estimated burial | Estimated accumulation DOC in EEZ waters | Carbon export to open ocean (estimated C export to open ocean) |

The estimated uptake of atmospheric carbon in the North American EEZ amounts to 6.4% of the global ocean uptake of atmospheric CO2 (est. 2,500 Tg C yr−1). The North American EEZ only represents ~4% of the global ocean surface area, thus the CO2 uptake is about 50% more efficient in the North American EEZ than the global average. Given the importance of coastal margins, both in contributing to carbon budgets and in the societal benefits they provide, further efforts to improve assessments of the carbon cycle in these regions are paramount. It is critical to maintain and expand existing coastal observing programs, continue national and international coordination and integration of observations, modeling capabilities, and stakeholder needs.

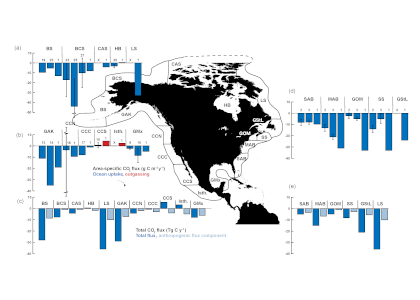

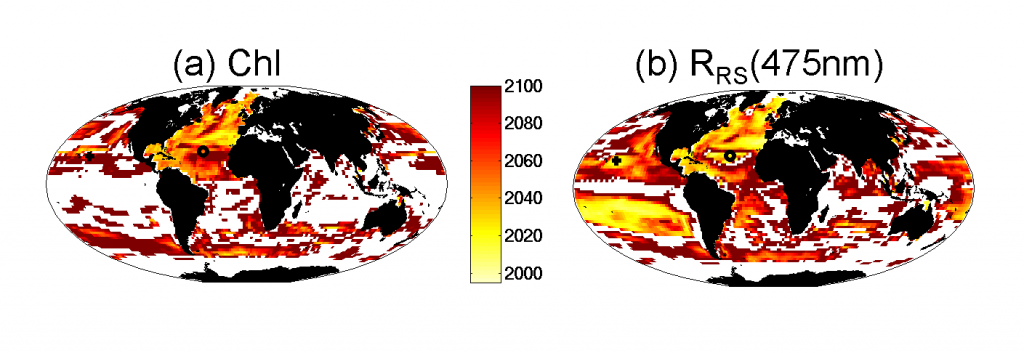

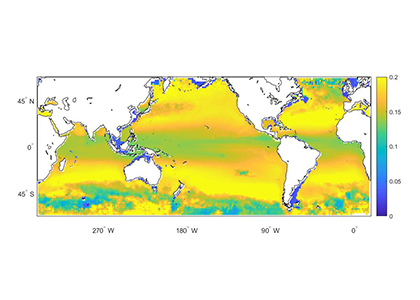

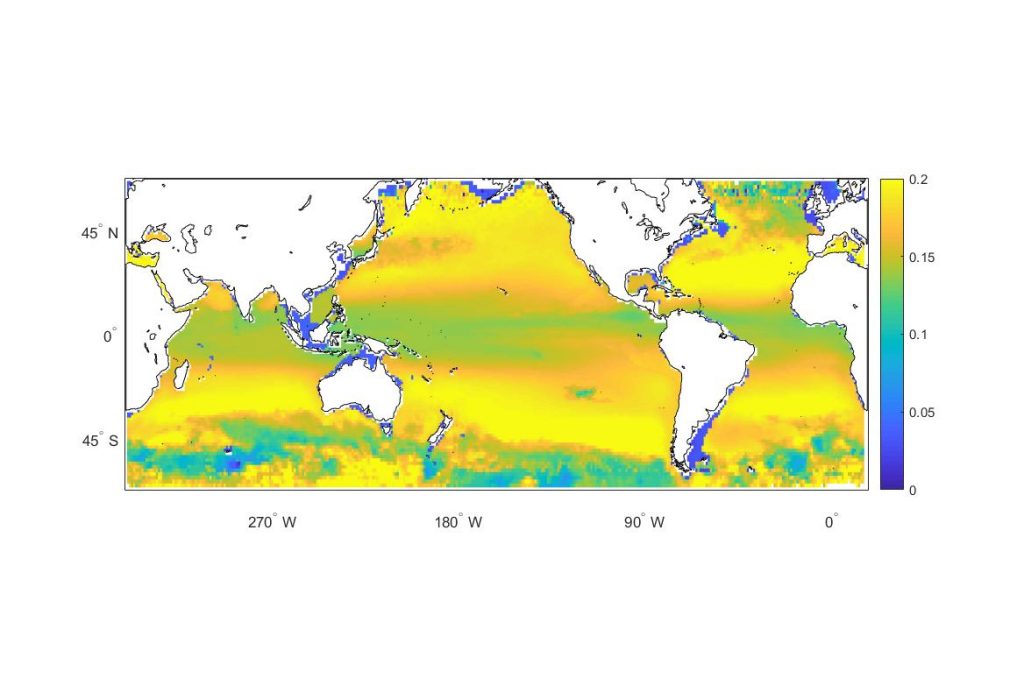

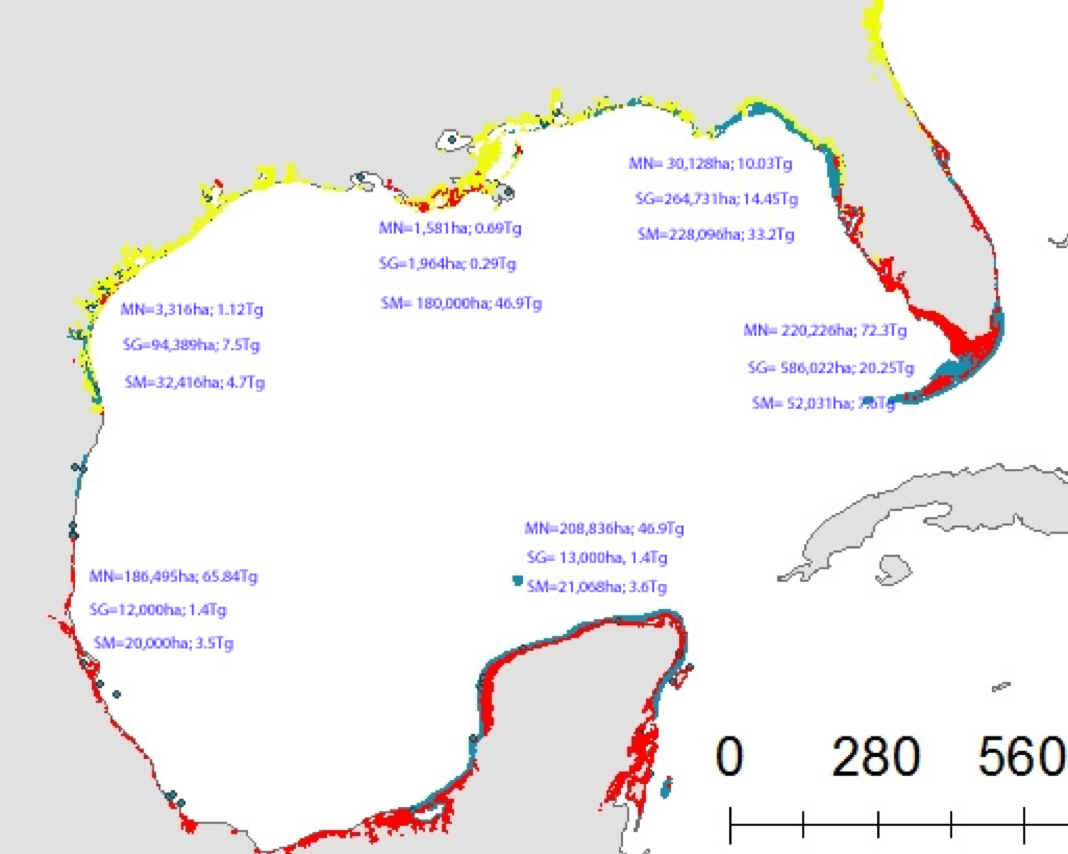

Figure: Area-specific carbon fluxes for North American coastal regions (a, b and d) and total fluxes for a decomposition of the EEZ (c, e).

Authors:

Katja Fennel, Timothée Bourgeois (Dalhousie University, Canada)

Simone Alin, Richard A. Feely, Adrienne Sutton (NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory)

Leticia Barbero (NOAA Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory)

Wiley Evans (Hakai Institute, Canada)

Sarah Cooley (Ocean Conservancy)

John Dunne (NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory)

Jose Martin Hernandez-Ayon (Autonomous University of Baja California, Mexico)

Xinping Hu (Texas A&M University)

Steven Lohrenz (University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth)

Frank Muller-Karger, Lisa Robbins (University of South Florida)

Raymond Najjar (Pennsylvania State University)

Elizabeth Shadwick (CSIRO, Australia)

Samantha Siedlecki, Penny Vlahos (University of Connecticut)

Nadja Steiner (Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada)

Daniela Turk (Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory)

Zhaohui Aleck Wang (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)