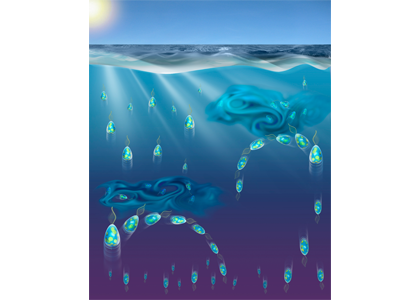

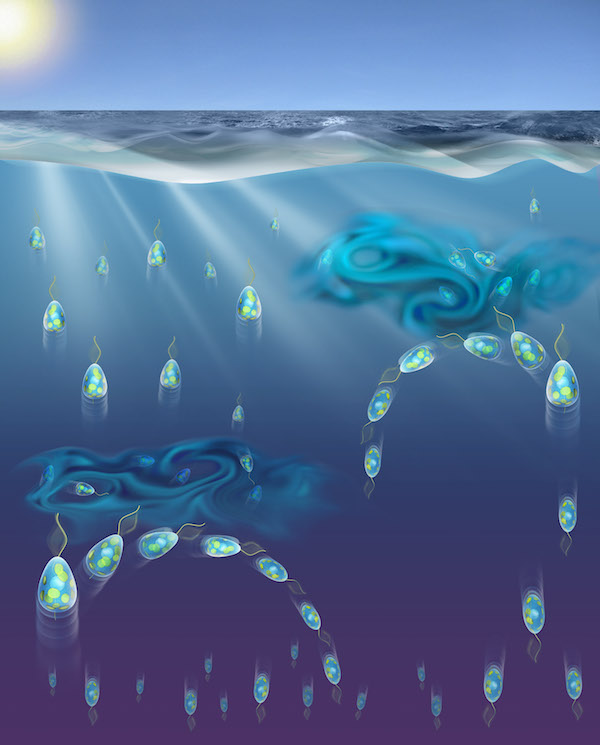

What controls the amount of organic carbon entering the deep ocean? In the sunlit layer of the ocean, phytoplankton transform inorganic carbon to organic carbon via a process called photosynthesis. As these particulate forms of organic carbon stick together, they become dense enough to sink out of the sunlit layer, transferring large quantities of organic carbon to the deep ocean and out of contact with the atmosphere.

However, all is not still in the dark ocean. Microbial organisms such as bacteria, and zooplankton consume the sinking, carbon-rich particles and convert the organic carbon back to its original inorganic form. Depending on how deep this occurs, the carbon can be physically mixed back up into the surface layers for exchange with the atmosphere or repeat consumption by phytoplankton. In a recent study published in Biogeosciences, researchers used field data and an ecosystem model in three very different oceanic regions to show that zooplankton are extremely important in determining how much carbon reaches the deep ocean.

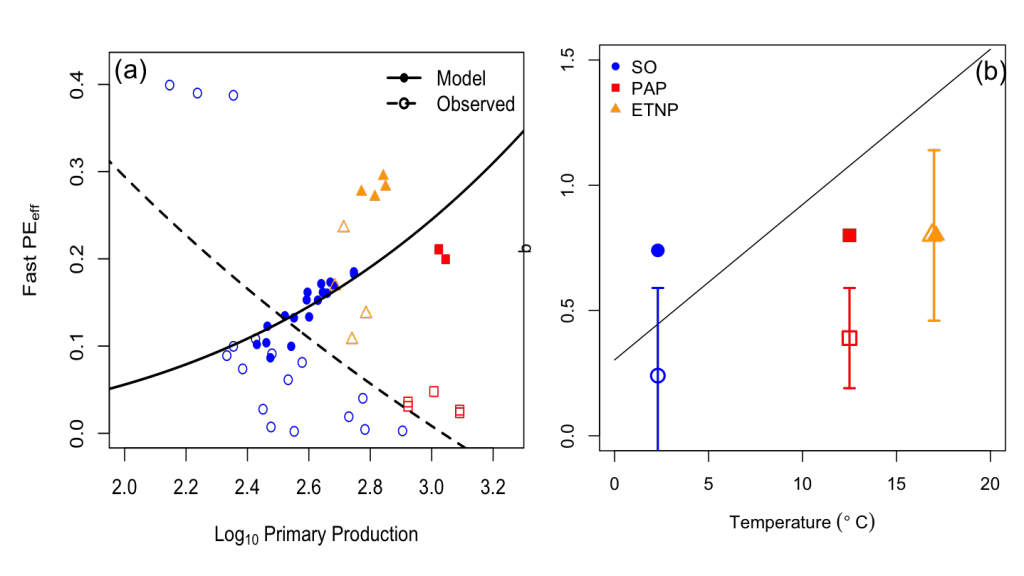

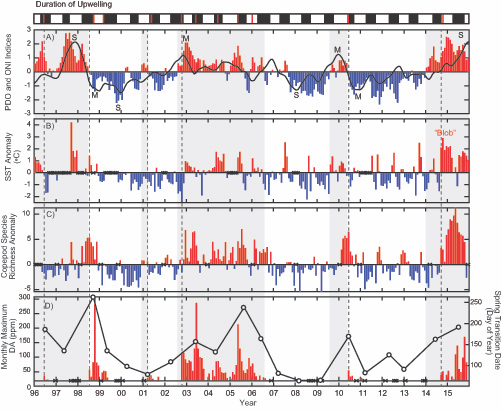

Figure 1. Particle export and transfer efficiency to the deep ocean in the Southern Ocean (SO, blue circles), North Atlantic Porcupine Abyssal Plain site (PAP, red squares) and the Equatorial Tropical North Pacific (ETNP, orange triangles) oxygen minimum zone. a) particle export efficiency of fast sinking particles (Fast PEeff) against primary production on a Log10 scale. b) transfer efficiency of particles to the deep ocean expressed as Martin’s b (high b = low efficiency). Error bars in b) are standard error of the mean for observed particles, error too small in model to be seen on this plot.

In the Southern Ocean (SO), zooplankton graze on phytoplankton and produce rapidly sinking fecal pellets, resulting in an inverse relationship between particle export and primary production (Fig. 1a). In the North Atlantic (NA), the efficiency with which particles are transferred to the deep ocean is comparable to that of the Southern Ocean, suggesting similar processes apply; but in both regions, there is a large discrepancy between the field data and the ecosystem model (Fig. 1b), which poorly represents particle processing by zooplankton. Conversely, much better data-model matches are observed in the equatorial Pacific, where lower oxygen concentrations mean fewer zooplankton; this reduces the potential for zooplankton-particle interactions that reduce particle size and density, resulting in a lower transfer efficiency.

This result suggests that mismatches between the data and model in the SO and NA may be due to the lack of zooplankton-particle parameterizations in the model, highlighting the potential importance of zooplankton in regulating carbon export and storage in the deep ocean. Zooplankton parameterizations in ecosystem models must be enhanced by including zooplankton fragmentation of particles as well as consumption. Large field programs such as EXPORTS could help constrain these parameterisation by collecting data on zooplankton-particle interaction rates. This will improve our model estimates of carbon export and our ability to predict future changes in the biological carbon pump. This is especially important in the face of climate-driven changes in zooplankton populations (e.g. oxygen minimum zone (OMZ) expansion) and associated implications for ocean carbon storage and atmospheric carbon dioxide levels.

Authors:

Emma L. Cavan (University of Tasmania)

Stephanie A. Henson (National Oceanography Centre, Southampton)

Anna Belcher (University of Southampton)

Richard Sanders (National Oceanography Centre, Southampton)

Christiana Ade is a first-year PhD student at North Carolina State University in the Marine, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences Department. She researches wetlands and coastal environments using satellite remote sensing and field measurements. Her research includes water quality mapping, establishing new environmental indicators, and determining satellite resolution requirements for adequately monitoring wetlands.

Christiana Ade is a first-year PhD student at North Carolina State University in the Marine, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences Department. She researches wetlands and coastal environments using satellite remote sensing and field measurements. Her research includes water quality mapping, establishing new environmental indicators, and determining satellite resolution requirements for adequately monitoring wetlands. Henry Houskeeper

Henry Houskeeper  Suhey Ortiz Rosa is a PhD student conducting research with Dr. Roy Armstrong in Bio-Optical Oceanography at the Department of Marine Sciences at the University of Puerto Rico- Mayagüez (UPRM). In 2005, she completed a B.S. in Coastal Marine Biology at the University of Puerto Rico- Humacao, and in 2010, a MS in Chemical Oceanography at UPRM. Suhey’s work focuses on the biogeochemistry of coastal waters and coral reefs, validating algorithms from satellite imagery of complex optical waters, remote sensing, and GIS. Previously, she worked on CDOM characterization with PARAFAC, mapping marine species distribution with the GAP-Analysis Project of Puerto Rico and later with watershed analysis of sedimentation processes on coral reefs.

Suhey Ortiz Rosa is a PhD student conducting research with Dr. Roy Armstrong in Bio-Optical Oceanography at the Department of Marine Sciences at the University of Puerto Rico- Mayagüez (UPRM). In 2005, she completed a B.S. in Coastal Marine Biology at the University of Puerto Rico- Humacao, and in 2010, a MS in Chemical Oceanography at UPRM. Suhey’s work focuses on the biogeochemistry of coastal waters and coral reefs, validating algorithms from satellite imagery of complex optical waters, remote sensing, and GIS. Previously, she worked on CDOM characterization with PARAFAC, mapping marine species distribution with the GAP-Analysis Project of Puerto Rico and later with watershed analysis of sedimentation processes on coral reefs. Sara Rivero-Calle is a postdoctoral researcher at the Levine Lab in the University of Southern California interested in projects that involve large datasets, combining remote sensing and in situ data to answer large-scale ecological questions. She first learned about satellite remote sensing during her MS program at the University of Puerto Rico working on mesophotic reef sponge ecology using Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. She earned a PhD from Johns Hopkins University, where she used the Continuous Plankton Recorder survey to study long-term changes in North Atlantic phytoplankton communities. Currently, Sara is conducting postdoctoral research on fine-scale variability and patchiness, combining remote sensing, float, and HPLC data with numerical models.

Sara Rivero-Calle is a postdoctoral researcher at the Levine Lab in the University of Southern California interested in projects that involve large datasets, combining remote sensing and in situ data to answer large-scale ecological questions. She first learned about satellite remote sensing during her MS program at the University of Puerto Rico working on mesophotic reef sponge ecology using Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. She earned a PhD from Johns Hopkins University, where she used the Continuous Plankton Recorder survey to study long-term changes in North Atlantic phytoplankton communities. Currently, Sara is conducting postdoctoral research on fine-scale variability and patchiness, combining remote sensing, float, and HPLC data with numerical models. Sarah Schlunegger is a PhD Student in the Program of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, advised by Prof. Jorge Sarmiento. Sarah uses Earth System Models to predict the timing, sequence and inter-dependence of emerging anthropogenic signals in the ocean, with a focus on the ocean’s acquisition of anthropogenic carbon and heat. The ocean provides a climate service by absorbing the atmosphere’s excess carbon and heat but at a cost, namely acidification and warming, which deteriorate marine habitats. Sarah’s primary research goal is to identify when and where changes in these heat/carbon sinks and their resulting impacts will be detectable in the ocean.

Sarah Schlunegger is a PhD Student in the Program of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, advised by Prof. Jorge Sarmiento. Sarah uses Earth System Models to predict the timing, sequence and inter-dependence of emerging anthropogenic signals in the ocean, with a focus on the ocean’s acquisition of anthropogenic carbon and heat. The ocean provides a climate service by absorbing the atmosphere’s excess carbon and heat but at a cost, namely acidification and warming, which deteriorate marine habitats. Sarah’s primary research goal is to identify when and where changes in these heat/carbon sinks and their resulting impacts will be detectable in the ocean.