The ocean’s “biological pump” regulates the atmosphere-ocean partitioning of carbon dioxide (CO2), and has likely contributed to significant climatic changes over Earth’s history (1, 2). It comprises two processes, separated vertically in the water column: (i) production of organic carbon and export from the surface euphotic zone (0-100m), mostly as sinking particles; and (ii) microbial remineralization of organic carbon to CO2 in deeper waters, where it cannot exchange with the atmosphere.

The depth of particulate organic carbon (POC) remineralization controls the longevity of carbon storage in the ocean (3), and strongly influences the atmospheric CO2 concentration (4). CO2 released in the mesopelagic zone (100-1000m) is returned to the atmosphere on annual to decadal timescales, whereas POC remineralization in the deep ocean (>1000m) sequesters carbon for centuries or longer (5). A common metric for the efficiency of the biological pump is thus the fraction of sinking POC that reaches the deep ocean before remineralization (6), referred to as the particle transfer efficiency, or Teff.

Currently, the factors that govern particle remineralization depth are poorly understood and crudely represented in climate models, compared to the lavish treatment of POC production by autotrophic communities in the surface (7). This compromises our ability to predict the biological pump’s response to anthropogenic warming, and its potential feedback on atmospheric CO2 (8). Over the last decade, a number of studies have identified a promising path towards closing this gap. If systematic spatial variations inTeff can be identified throughout the modern ocean, we might discern their underlying environmental or ecological causes (9, 10). However, direct observations from sediment traps are too sparse to constrain time-mean particle fluxes through the mesopelagic zone at the global scale, and no consensus pattern of Teff has emerged from these analyses.

Particle flux reconstruction

Instead of relying on sparse particle flux observations, a recent study took an alternative approach, leveraging the geochemical signatures that are left behind when particles remineralize (11). Products of remineralization include inorganic nutrients like phosphate (PO43-), whose global distributions are well characterized by hundreds of thousands of shipboard observations (12). In shallow subsurface waters, nutrient accumulation reflects the remineralization of both organic particles and dissolved organic matter, which is advected and entrained from the euphotic zone. Dissolved organic phosphorous (DOP) decomposes rapidly, and is almost completely absent

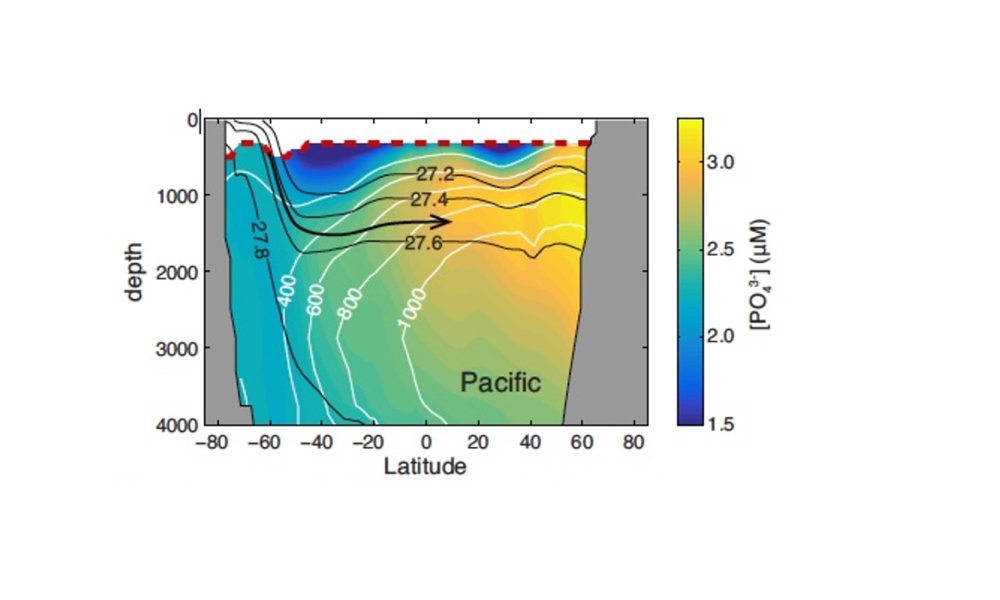

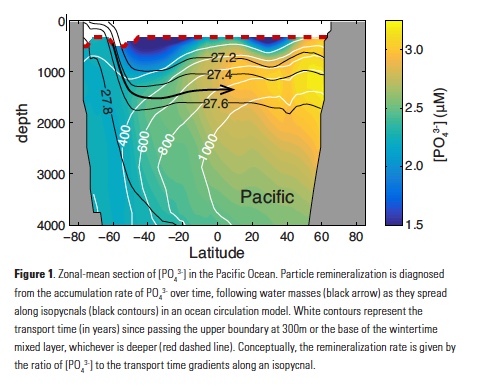

In shallow subsurface waters, nutrient accumulation reflects the remineralization of both organic particles and dissolved organic matter, which is advected and entrained from the euphotic zone. Dissolved organic phosphorous (DOP) decomposes rapidly, and is almost completely absent by depths of ~300m in the stratified low latitude ocean (13), and below the wintertime mixed layer in high latitudes (14). Deeper in the water column, particulate organic phosphorous (POP) remineralization is the only process that generates PO43- within water masses as they flow along isopycnal surfaces (Fig. 1). Rates of POP remineralization can therefore be diagnosed from the accumulation rate of PO43- along transport pathways in an ocean circulation model. This calculation requires a very faithful representation of the large-scale circulation, as provided by the Ocean Circulation Inverse Model (OCIM), whose flow fields are optimized to match observed water mass tracer distributions (15).

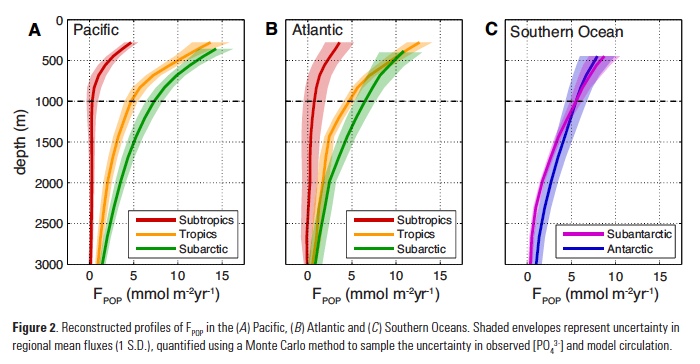

Assuming that organic matter burial in sediments is negligible, the integrated POP remineralization beneath a given depth horizon is equal to the flux of POP (FPOP) through that horizon, allowing complete reconstruction of flux profiles from ~300m to the deep ocean. Averaging these fluxes over large ocean regions serves to extract the large-scale signal from small-scale noise (Fig. 2). Regional-mean FPOP profiles show striking differences in shape and magnitude between subarctic, tropical, and subtropical regions, which are remarkably consistent between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans (Fig 2a,b). FPOP near 300m is similar in subarctic and tropical zones, but attenuates faster through the mesopelagic in the tropics, reaching values of ~5mmol m-2yr-1 at 1000m, compared to ~7mmol m-2yr-1 in subarctic oceans. Subtropical FPOP attenuates even faster, and is indistinguishable from zero throughout most of the water column. In the Southern Ocean, FPOP is ~5mmol m-2yr-1 at 1000m in both the Antarctic and subantarctic regions, but the subantarctic flux profile attenuates slightly faster (Fig. 2c).

Patterns of transfer efficiency and underlying mechanisms

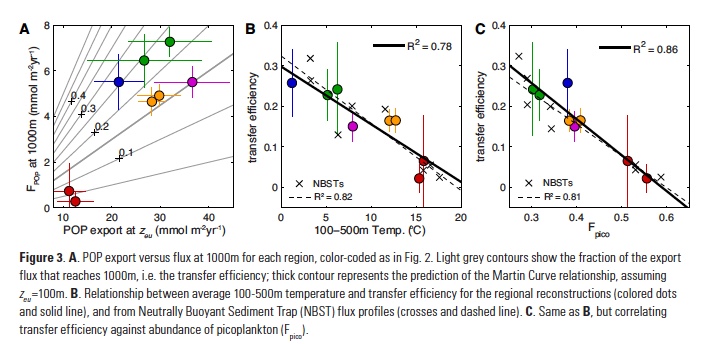

While these reconstructions place a robust constraint on POP fluxes to the deep ocean, they do not constrain rates of POP export at the base of the euphotic zone (zeu) that are needed to estimate the particle transfer efficiency (Teff). Remote sensing approaches are widely used to estimate large-scale organic carbon export, which can be converted to POP using an empirical relationship for particulate P:C ratios (16). However, multiple algorithms have been proposed to estimate net primary production and convert it to export, yielding widely different regional-mean rates (11). One way to pare down this variability is to weight each algorithm based on its ability to reproduce tracer-based export estimates in each ocean region (17, 18). This yields an “ensemble” estimate for the areal-mean POP export rate in each region, and an uncertainty range that reflects both observational error and the variability between satellite algorithms (Fig. 3a).

Combining the ensemble estimates of POP export with reconstructed FPOP at 1000m reveals a systematic pattern of transfer efficiency from zeu to the deep ocean (Fig. 3a). The subtropics exhibit the lowest Teff of ~5%, significantly lower than expected from the canonical Martin Curve relationship (19), which is often considered to represent an “average” particle flux profile. In the tropics and the subantarctic zone of the Southern Ocean, Teff clusters close to the Martin Curve prediction of ~15%. The subarctic and Antarctic regions (i.e. high latitudes) are the most efficient at delivering the surface export flux to depth with Teff>25%, although these values are also associated with the largest uncertainty (Fig. 3a).

What controls the strong latitudinal variation of transfer efficiency? Particle flux attenuation is determined by the sinking speed and bacterial decomposition rate of particles: fast sinking and slow decomposition both result in greater delivery of organic matter to the deep ocean. Decomposition rates increase as a function of temperature in laboratory incubation studies (20), controlled by the temperature-dependence of bacterial metabolism. In a recent compilation of Neutrally Buoyant Sediment Trap (NBST) observations, particle flux attenuation was strongly correlated with upper ocean temperature between 100-500m (21), consistent with this effect. An almost identical temperature relationship explains ~80% of the variance in reconstructed regional Teff estimates (Fig. 3b).

An equally compelling argument can be made for particle sinking speeds controlling the pattern of Teff. According to the current paradigm of marine food webs (22), communities dominated by small phytoplankton export small particles that sink slowly, relative to the large aggregates and fecal pellets produced when large plankton dominate. The fraction of photosynthetic biomass contributed by tiny picoplankton (Fpico) varies from <30% in subarctic regions to >55% in oligotrophic subtropical regions (23), and explains ~86% of the variance in reconstructed Teff (Fig. 3c). Fpico also predicts flux attenuation in NBST profiles as skillfully as upper-ocean temperature (R2 = 0.81 and 0.82 respectively), but was not considered previously (21). Due to the spatial covariation of these factors in the ocean, statistical analysis alone is insufficient to determine the relative contributions of temperature and particle size to latitudinal variations in transfer efficiency.

Conclusions and future directions

Reconstructing deep-ocean particle fluxes has left us with a clearer understanding of the biological pump in the contemporary ocean and its climate sensitivity. Deep remineralization in high latitude regions results in efficient long-term carbon storage, whereas carbon exported in subtropical regions is recirculated to the atmosphere on short timescales (11). Atmospheric CO2 is likely more sensitive to increased high latitude nutrient utilization during glacial periods than previously recognized, whereas the expansion of subtropical gyres in a warming climate might result in a less efficient biological pump.

One caveat is that the new results highlighted here constrain POP transfer efficiency, not POC, and the two might be decoupled by preferential decomposition of one element relative to the other. The close agreement of these results with Neutrally Buoyant Sediment Trap observations (which measure POC) is encouraging, and suggests that the reconstructed pattern ofTeff is applicable to carbon. More widespread deployment of NBSTs, which circumvent the sampling biases of older sediment trap systems (24), would help confirm or refute this conclusion. A second limitation is that the wide degree of uncertainty in high latitude export rates (Fig. 3a) obscures estimates ofTeff in these regions. New tracer-based methods to integrate export across the seasonal cycle (25) will hopefully close this gap and enable more careful groundtruthing of satellite predictions.

Two plausible mechanisms –particle size and temperature – have been identified to explain large latitudinal variations in transfer efficiency, and new observational systems hold the potential to disentangle their effects. Underwater Visual Profilers (UVP) can now accurately resolve the size distribution of particles in mesopelagic waters (26). Although UVPs provide only instantaneous snapshots (quite literally) of the particle spectrum rather than time-mean properties, large compilations of these data will help establish the spatial pattern of particle size and its relationship to microbial community structure. In parallel, ongoing development of the RESPIRE particle incubator will allow for in-situ measurement of POC respiration (27), and better establish its temperature sensitivity.

Over the next few years, the upcoming EXport Processes in the Ocean from RemoTe Sensing (EXPORTS) campaign stands to revolutionize our understanding of the fate of organic carbon (28). These insights will allow for a more balanced treatment of the “dark side” of the biological pump in global climate models, compared to euphotic zone processes, improving our predictions of biological carbon sequestration in a warming ocean.

Author

By Thomas Weber (University of Rochester)

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by NSF grant OCE-1635414 and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (GBMF 3775).

References

1. J. L. Sarmiento et al., Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 325, 3–21 (1988).

2. A. Mart.nez-Garc.a et al., Science 343, 1347–50 (2014).

3. U. Passow, C. Carlson, Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 470, 249–271 (2012).

4. E. Y. Kwon, F. Primeau, J. L. Sarmiento, Nat. Geosci. 2, 630–635 (2009).

5. T. Devries, F. Primeau, C. Deutsch, Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, 1–5 (2012).

6. P. J. Lam, S. C. Doney, J. K. B. Bishop, Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 25, 1–14 (2011).

7. J. K. Moore, S. C. Doney, J. a. Kleypas, D. M. Glover, I. Y. Fung, Deep. Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 49, 403–462 (2002).

8. L. Bopp et al., Biogeosci. 10, 6225–6245 (2013).

9. S. a. Henson, R. Sanders, E. Madsen, Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 26, 1–14 (2012).

10. M. J. Lutz, K. Caldeira, R. B. Dunbar, M. J. Behrenfeld, J. Geophys. Res. 112, C10011 (2007).

11. T. Weber, J. A. Cram, S. W. Leung, T. Devries, C. Deutsch, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 113, 8606–8611 (2016).

12. H. E. Garcia et al., NOAA World Ocean Atlas (2010).

13. J. Abell, S. Emerson, P. Renaud, J. Mar. Res. 58, 203–222 (2000).

14. S. Torres-Vald.s et al., Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 23, 1–16 (2009).

15. T. Devries, Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 28, 631–647 (2014).

16. E. D. Galbraith, A. C. Martiny, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci., 201423917 (2015).

17. M. K. Reuer, B. A. Barnett, M. L. Bender, P. G. Falkowski, M. B. Hendricks, Deep. Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 54, 951–974 (2007).

18. S. Emerson, Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 28, 14–28 (2014).

19. J. H. Martin, G. A. Knauer, D. M. Karl, W. W. Broenkow, Deep Sea Res. Part A, Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 34, 267–285 (1987).

20. M. H. Iversen, H. Ploug, Biogeosciences. 10, 4073–4085 (2013).

21. C. M. Marsay, R. J. Sanders, S. A. Henson, K. Pabortsava, E. P. Achterberg, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci., 112, 1089–1094 (2014).

22. D. A. Siegel et al., Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 28, 181–196 (2014).

23. T. Hirata et al., Biogeosci. 8, 311–327 (2011).

24. K. O. Buesseler et al., Science 316, 567–570 (2007).

25. S. M. Bushinsky, S. Emerson, Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 29, 2050–2060 (2015).

26. M. Picheral et al., Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods. 8, 462–473 (2010).

27. A. M. P. McDonnell, P. W. Boyd, K. O. Buesseler, Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 29, 175–193 (2015).

28. D. A. Siegel et al., Front. Mar. Sci. 3, 1–10 (2016).