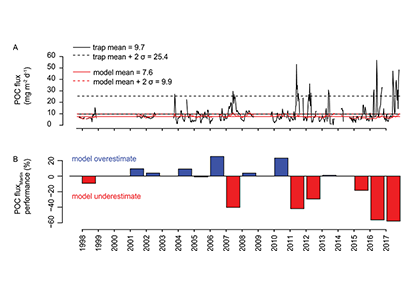

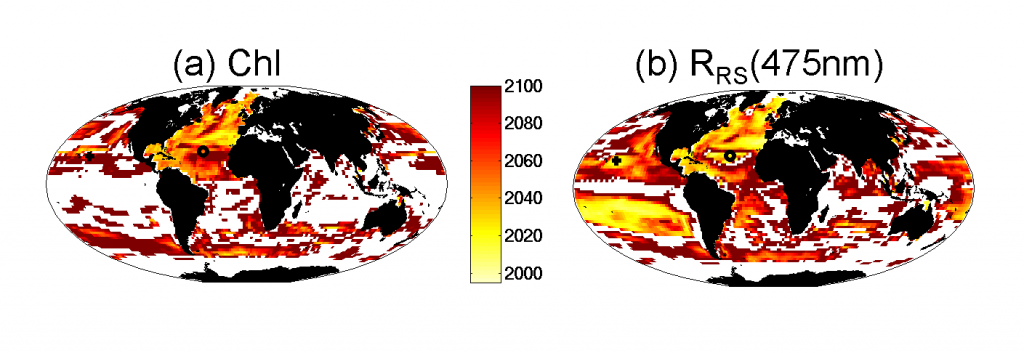

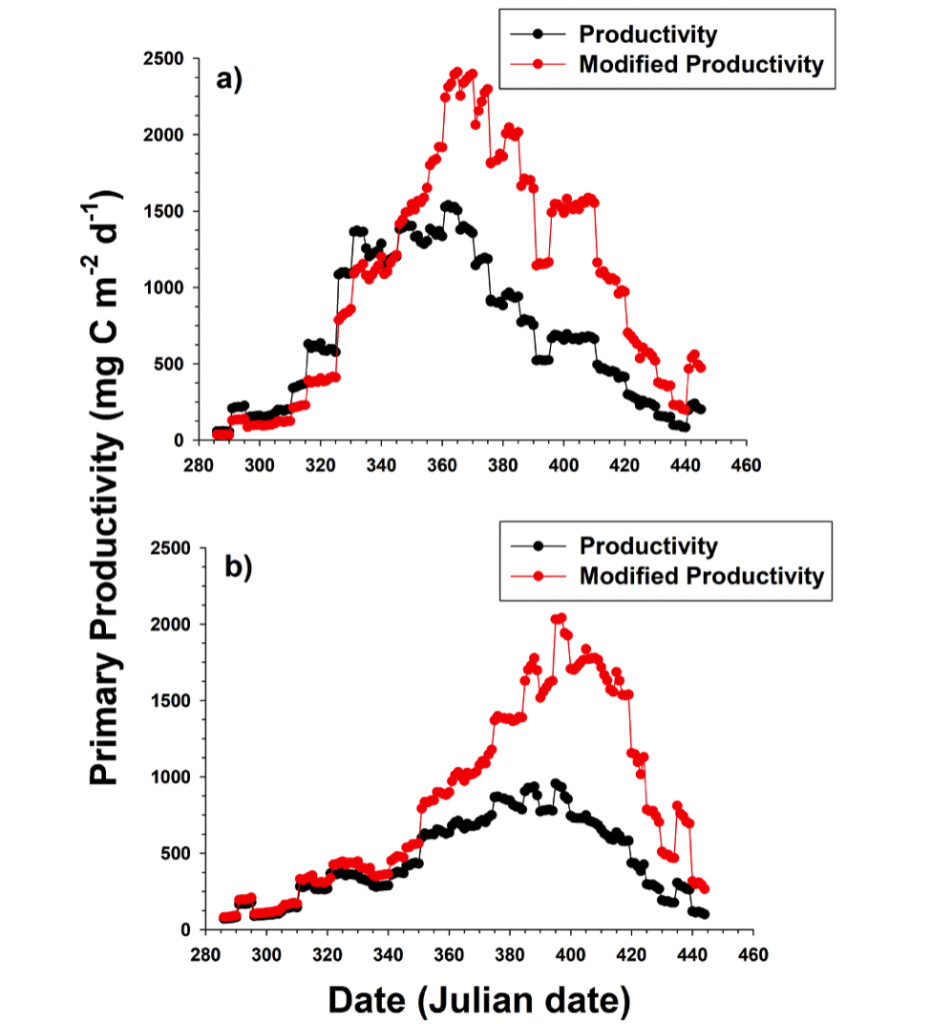

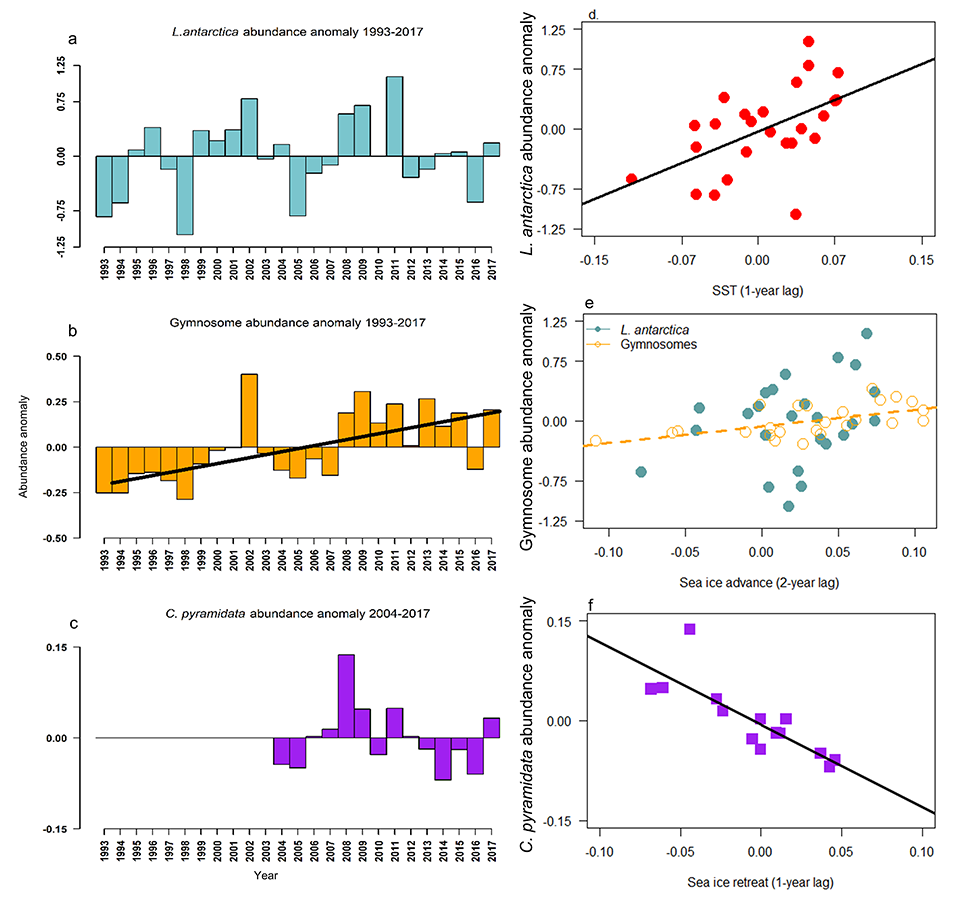

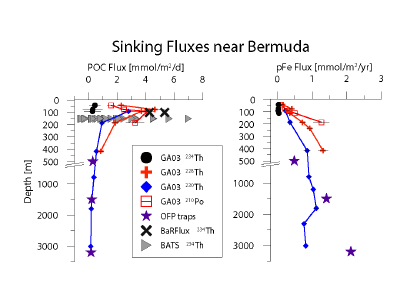

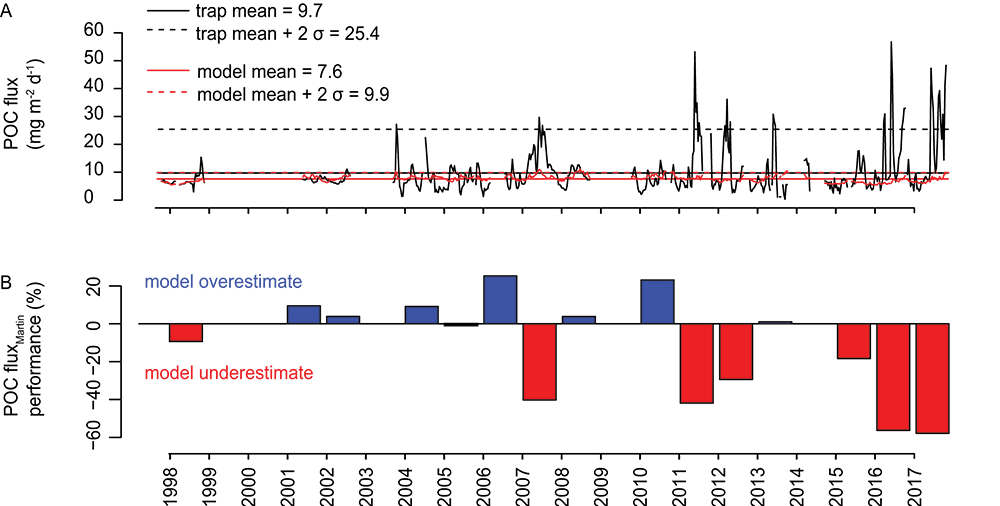

Temporal fluctuations in the oceanic carbon budget play an important role in the cycling of organic matter from production in surface waters to consumption and sequestration in the deep ocean. A 29-year time-series (1989-2017) of particulate organic carbon (POC) fluxes and seafloor measurements of oxygen consumption in the abyssal northeast Pacific (Sta. M, 4,000 m depth) recently revealed an increasing proportional contribution from episodic events over the past seven years. From 2011 to 2017, 43% of POC flux arrived during high-magnitude (≥ mean + 2 σ) episodic events. Time lags between changes in satellite-estimated export flux (EF), POC flux to the seafloor, and seafloor oxygen consumption varied from 0 to 70 days among six flux events, which could be attributed to variable remineralization rates and/or particle sinking speeds. The Martin equation, a commonly used model to estimate carbon flux, predicted background fluxes well but missed episodic fluxes, subsequently underestimating the measured fluxes by almost 50% (Figure 1). This study reveals the potential importance of episodic POC pulses into the deep sea in the oceanic carbon budget, which has implications for observing infrastructure, model development, and field campaigns focused on quantifying carbon export.

Figure Caption: (A) Station M POC flux measured from sediment traps compared to Martin model estimates, from 1989 to 2017. (B) Model performance for years with >50% sampling coverage: (POC fluxMartin − POC fluxtrap)/POC fluxtrap 100.

Authors:

Kenneth Smith (MBARI)

Henry Ruhl (MBARI, NOC)

Christine Huffard (MBARI)

Monique Messié (MBARI, Aix Marseille Université)

Mati Kahru (Scripps)

See also https://www.mbari.org/carbon-pulses-climate-models/