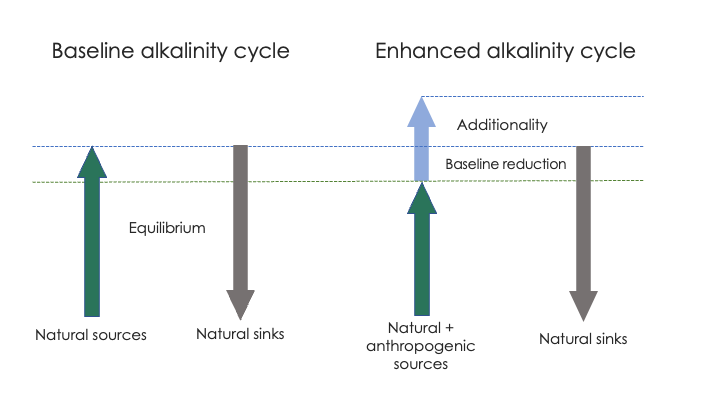

The ultimate goal of marine carbon dioxide (CO2) removal (mCDR) is to sequester more atmospheric CO2 in the ocean than the ocean already does today. As such, any mCDR deployment must lead to quantifiably more CO2 sequestration in the ocean than would have happened without the deployment. This requirement is referred to as “additionality.”

To understand how additionality of CO2 removal is relevant for Ocean Alkalinity Enhancement (OAE) we need to recall what OAE seeks to do. Essentially, OAE accelerates a natural process (weathering) that absorbs protons (H+) in liquid media through geochemical reactions. This anthropogenically enhanced “buffering” results in fewer freely available protons and thus a shift in the marine carbonate system away from CO2 and towards carbonate ions (CO32+), a shift that enables oceanic uptake of atmospheric CO2. However, the anthropogenically buffered protons are then no longer available to be absorbed by natural weathering processes (e.g., calcium carbonate dissolution). Therefore, anthropogenic buffering of seawater pH partially replaces natural buffering (and associated CO2 sequestration) that would have occurred in the absence of OAE. A recent paper (Bach, 2024) describes this “additionality problem” in the context of OAE, and through a series of incubation experiments that emulate a high-energy wave zone (constant mixing), the author investigates how different forms of anthropogenic alkalinity (e.g., sodium hydroxide, steel slag, and olivine) interact with natural alkalinity sources (beach sand) and the subsequent impacts on atmospheric CO2 drawdown. While many questions will require more targeted study, this study represents a foundational baseline for future OAE experimentation and provides preliminary insights on siting and methods of anthropogenic alkalinity addition.

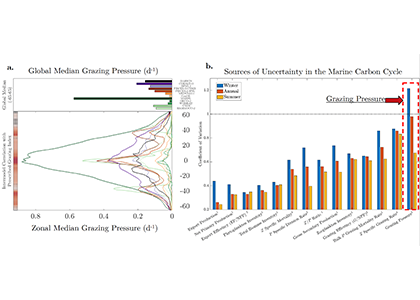

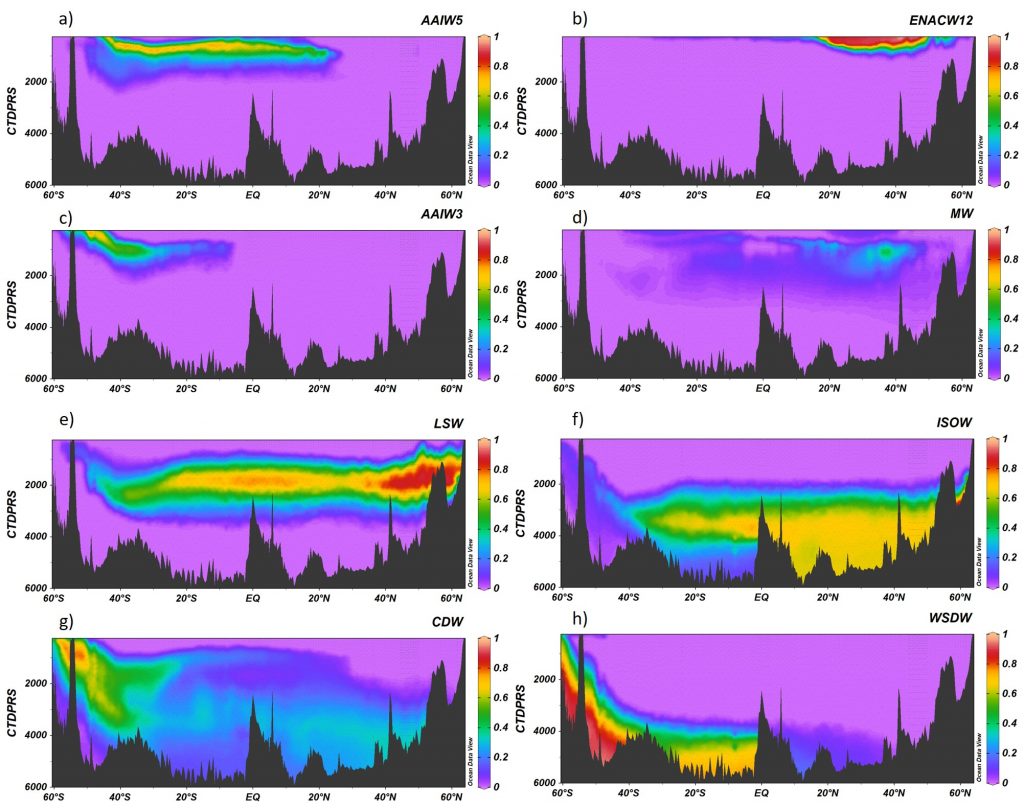

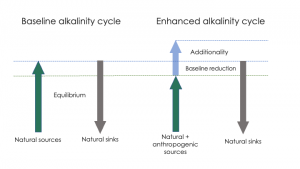

Figure caption: Simple schematic of the additionality problem. In the baseline state (left), alkalinity sources and sinks are (assumed to be) in equilibrium. The addition of an anthropogenic alkalinity source (right) to the baseline system may reduce alkalinity inputs via natural sources. The reduction of natural sources must be subtracted from the anthropogenic sources to correctly calculate the additional CO2 sequestration potential of OAE.

Author

Lennart Bach (Univ. Tasmania)