Ocean temperature extreme events such as marine heatwaves are expected to intensify in coming decades due to anthropogenic warming. Although the effects of marine heatwaves on large plants and animals are becoming well documented, little is known about how these warming events will impact microbes that regulate key biogeochemical processes such as ocean carbon uptake and export, which represent important feedbacks on the global carbon cycle and climate.

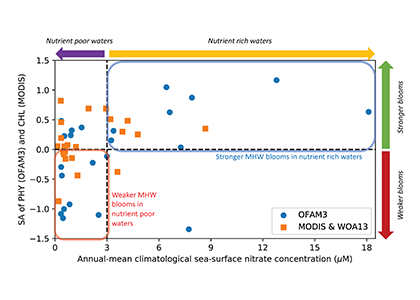

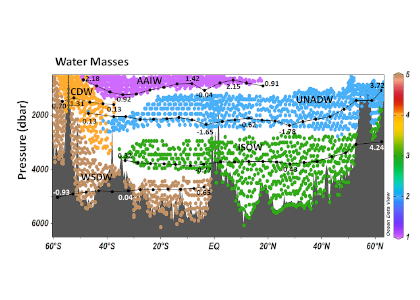

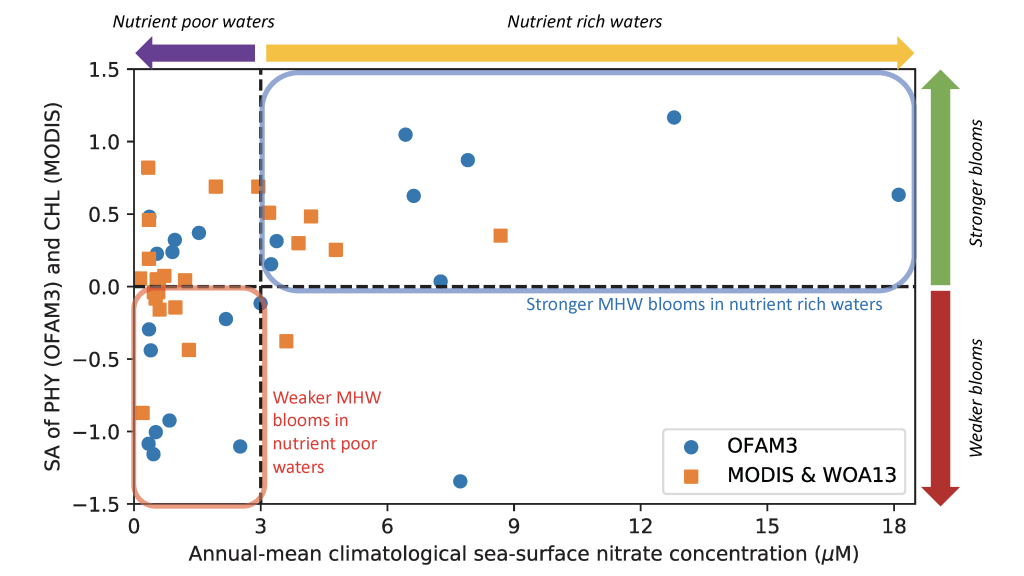

Figure caption: Relationship between phytoplankton bloom response to marine heatwaves and background nitrate concentration in the 23 study regions. X-axis denotes the annual-mean sea-surface nitrate concentration based on the model simulation (1992-2014; OFAM3, blue) and the in situ climatology (WOA13, orange). Y-axis denotes the mean standardised anomalies (see Equation 1 of the paper) of simulated sea-surface phytoplankton nitrogen biomass (1992-2014; OFAM3, blue) and observed sea-surface chlorophyll a concentration (2002-2018; MODIS, orange) during the co-occurrence of phytoplankton blooms and marine heatwaves.

In a recent study published in Global Change Biology, authors combined model simulations and satellite observations in tropical and temperate oceanographic regions over recent decades to characterize marine heatwave impacts on phytoplankton blooms. The results reveal regionally‐coherent anomalies depicted by shallower surface mixed layers and lower surface nitrate concentrations during marine heatwaves, which counteract known light and nutrient limitation effects on phytoplankton growth, respectively (Figure 1). Consequently, phytoplankton bloom responses are mixed, but derive from the background nutrient conditions of a study region such that blooms are weaker (stronger) during marine heatwaves in nutrient-poor (nutrient-rich) waters.

Given the projected expansion of nutrient-poor waters in the 21st century ocean, the coming decades are likely to see an increased occurrence of weaker blooms during marine heatwaves, with implications for higher trophic levels and biogeochemical cycling of key elements.

Authors:

Hakase Hayashida (University of Tasmania)

Richard Matear (CSIRO)

Pete Strutton (University of Tasmania)