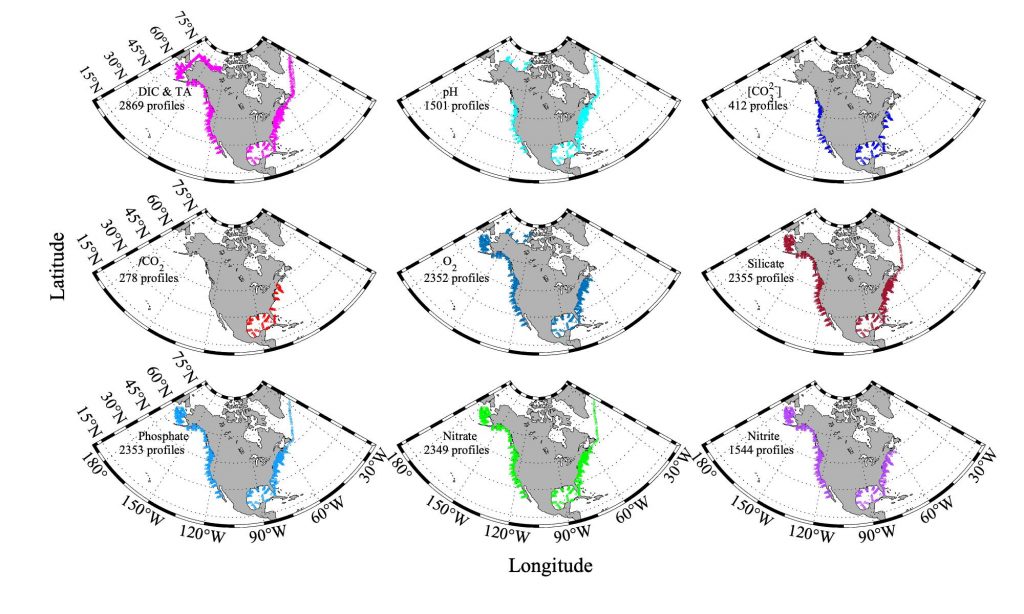

Coastal ecosystems are hotspots for commercial and recreational fisheries, and aquaculture industries that are susceptible to change or economic loss due to ocean acidification. These coastal ecosystems support about 90% of the global fisheries yield and 80% of the known marine fish species, and sustain ecosystem services worth $27.7 Trillion globally (a number larger than the U.S. economy). Despite the importance of these areas and economies, internally-consistent data products for water column carbonate and nutrient chemistry data in the coastal ocean—vital to understand and predict changes in these systems—currently do not exist. A recent study published in Earth Syst. Sci. Data compiled and quality controlled discrete sampling-based data—inorganic carbon, oxygen, and nutrient chemistry, and hydrographic parameters collected from the entire North American ocean margins—to create a data product called the Coastal Ocean Data Analysis Product for North America (CODAP-NA) to fill the gap. This effort will promote future OA research, modeling, and data synthesis in critically important coastal regions to help advance the OA adaptation, mitigation, and planning efforts by North American coastal communities; and provides a foothold for future synthesis efforts in the coastal environment.

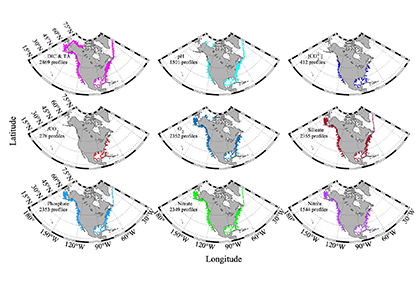

Figure caption. Sampling stations of the CODAP-NA data product.

Authors:

Li-Qing Jiang (University of Maryland; NOAA NCEI)

Richard A. Feely (NOAA PMEL)

Rik Wanninkhof (NOAA AOML)

Dana Greeley (NOAA PMEL)

Leticia Barbero (University of Miami; NOAA AOML)

Simone Alin (NOAA PMEL)

Brendan R. Carter (University of Washington; NOAA PMEL)

Denis Pierrot (NOAA AOML)

Charles Featherstone (NOAA AOML)

James Hooper (University of Miami; NOAA AOML)

Chris Melrose (NOAA NEFSC)

Natalie Monacci (University of Alaska Fairbanks)

Jonathan Sharp (University of Washington; NOAA PMEL)

Shawn Shellito (University of New Hampshire)

Yuan-Yuan Xu (University of Miami; NOAA AOML)

Alex Kozyr (University of Maryland; NOAA NCEI)

Robert H. Byrne (University of South Florida)

Wei-Jun Cai (University of Delaware)

Jessica Cross (NOAA PMEL)

Gregory C. Johnson (NOAA PMEL)

Burke Hales (Oregon State University)

Chris Langdon (University of Miami)

Jeremy Mathis (Georgetown University)

Joe Salisbury (University of New Hampshire)

David W. Townsend (University of Maine)