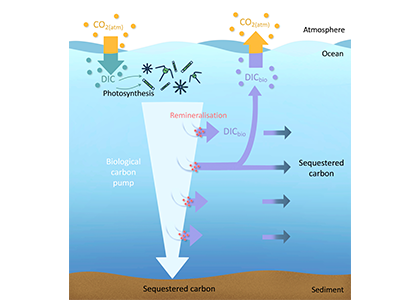

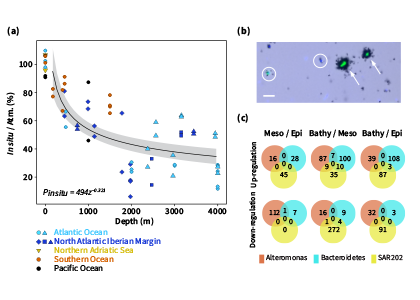

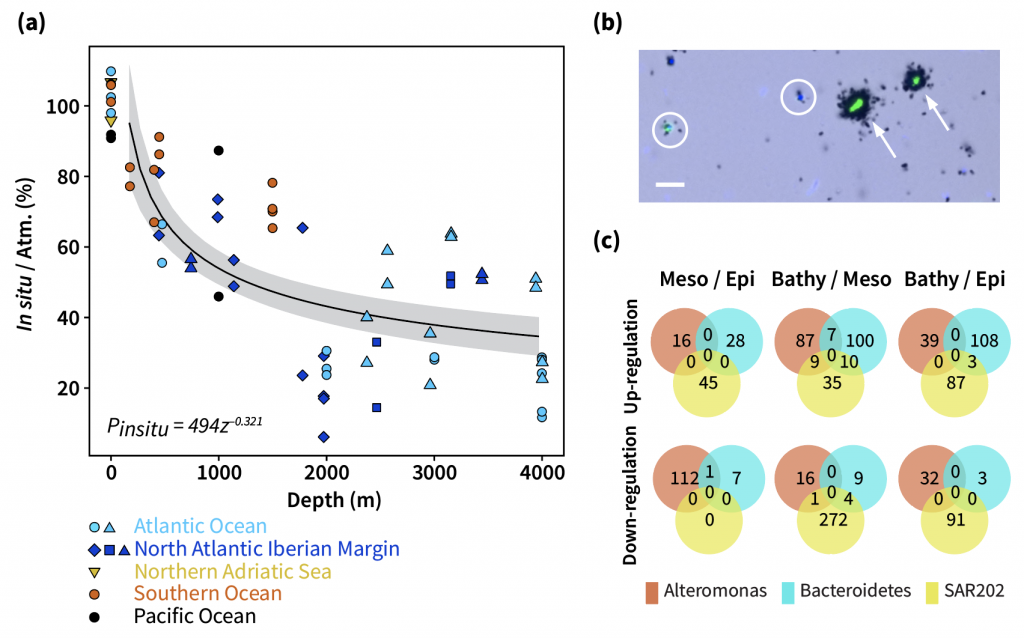

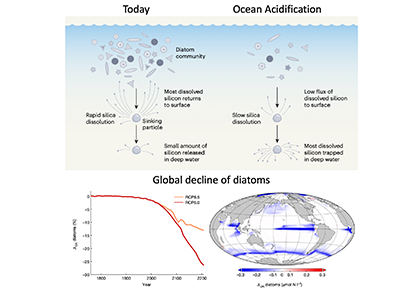

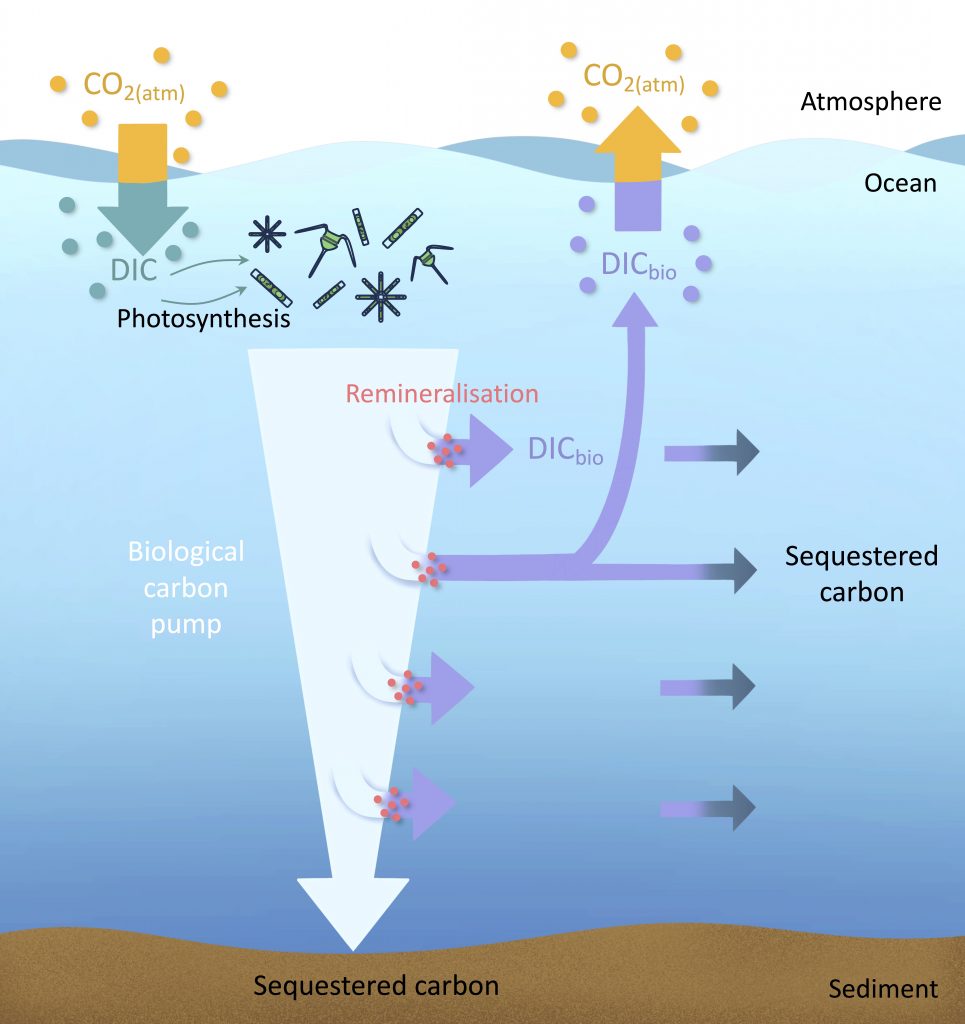

The biological carbon pump plays a key role in ocean carbon sequestration by transporting organic carbon from the upper ocean to deeper waters via three broad processes: the sinking of organic particles, vertical migration of organisms, and physical mixing. Most studies assume that century-scale carbon sequestration occurs only in the deep ocean, thus have missed sequestration that happens in the water column above 1,000m.

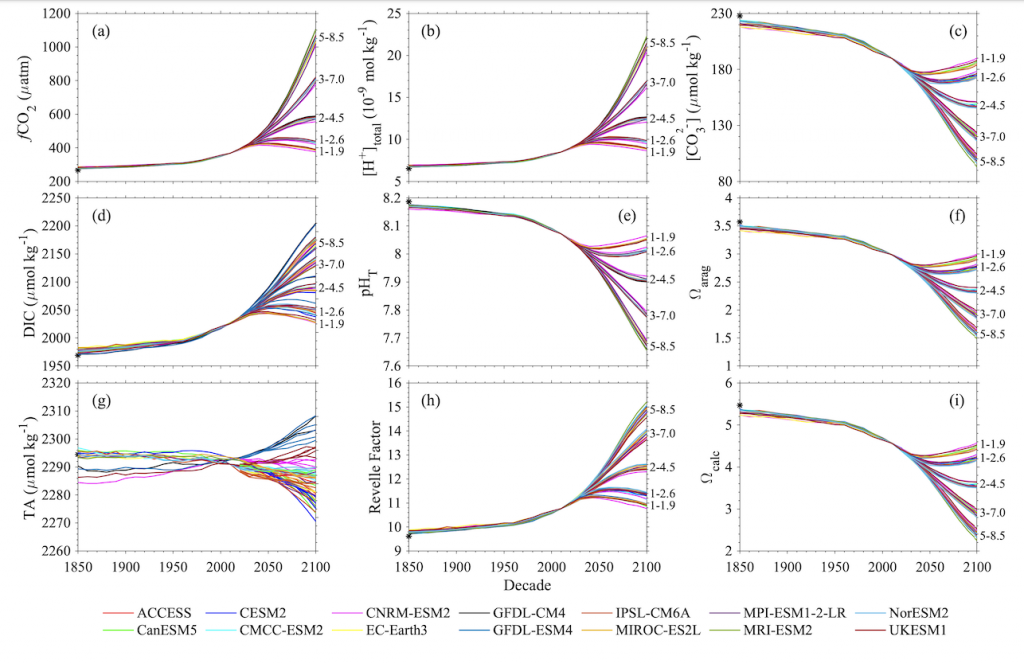

A recent publication reassessed the biological pump’s century-scale (≥100 years) carbon sequestration fluxes throughout the water column, by implementing the concept of ‘continuous vertical sequestration’ (CONVERSE). The resulting CONVERSE estimates were up to three times higher than those estimated at 1,000 m. This method shows that not only are these fluxes higher than previously thought, but also that vertical migration and physical mixing, which are generally neglected, make a significant contribution (20-30%) to carbon sequestration.

The CONVERSE method provides a new metric for calculations of the biological pump’s century-scale carbon sequestration flux that can be used to diagnose future changes in carbon sequestration fluxes in prognostic models of ocean biogeochemistry.

Interested in learning more? View more results and figures here.

Authors

Florian Ricour (Institute of Natural Sciences, Belgium)

Lionel Guidi (CNRS and Sorbonne University, France)

Marion Gehlen (CEA, CNRS and Paris-Saclay University, France)

Timothy Devries (University of California at Santa Barbara, USA)

Louis Legendre (Sorbonne University, France)

@LionelGuidi

@ComplexLov

@CNRS_INSU