Parasites are everywhere in the ocean. Including the microbial realm where a diverse, widespread group of protist parasites (Syndiniales) infect and kill a range of hosts, such as dinoflagellates, radiolarians, and even larger zooplankton. A complete Syndiniales infection cycle is only 2-3 days. First, the parasite is a free-living spore. Once inside a host, the parasite consumes the host’s carbon and becomes a larger multicellular organism (a trophont) eventually causing the host to burst open and release hundreds of new spores.

Like viruses, parasite lysis is expected to reroute organic carbon to the microbial loop, potentially decreasing the amount of carbon available for export to the deep sea. Yet, the role of Syndiniales in carbon cycling has been hard to define, as depth-specific infection dynamics and links to carbon export remain poorly understood.

Parasites are everywhere in the ocean. Including the microbial realm where a diverse, widespread group of protist parasites (Syndiniales) infect and kill a range of hosts, such as dinoflagellates, radiolarians, and even larger zooplankton. A complete Syndiniales infection cycle is only 2-3 days. First, the parasite is a free-living spore. Once inside a host, the parasite consumes the host’s carbon and becomes a larger multicellular organism (a trophont) eventually causing the host to burst open and release hundreds of new spores.

Like viruses, parasite lysis is expected to reroute organic carbon to the microbial loop, potentially decreasing the amount of carbon available for export to the deep sea. Yet, the role of Syndiniales in carbon cycling has been hard to define, as depth-specific infection dynamics and links to carbon export remain poorly understood.

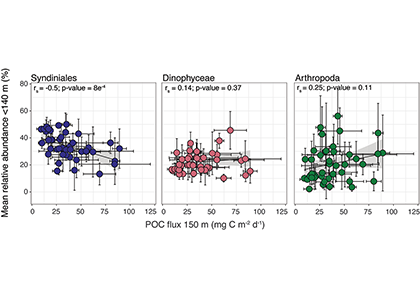

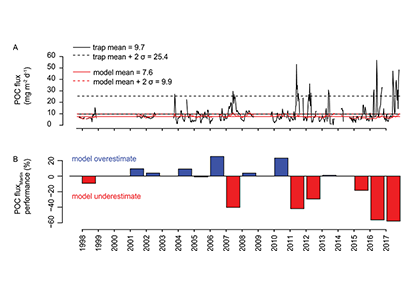

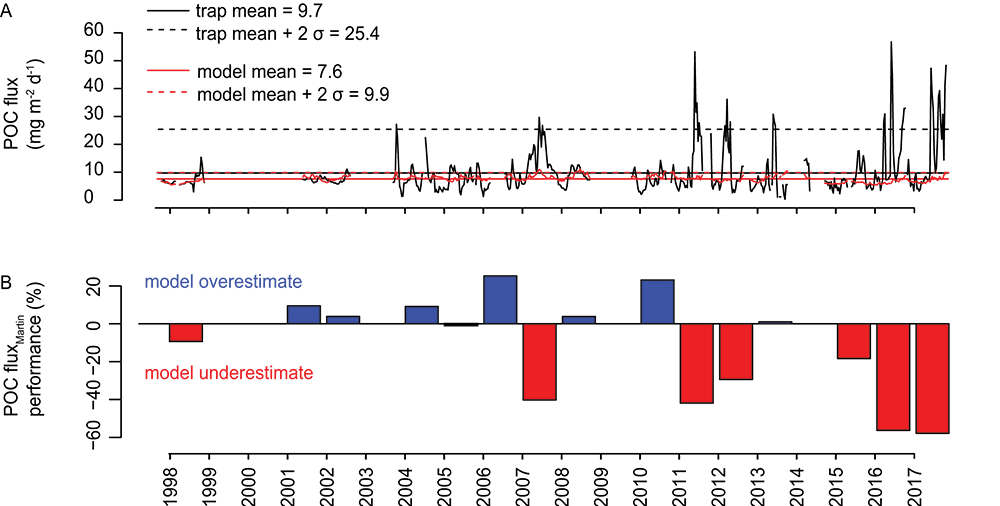

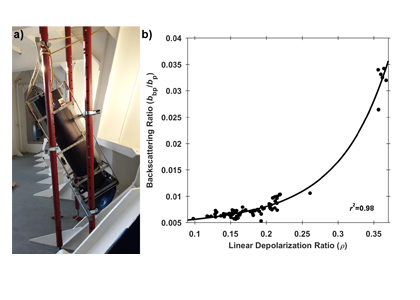

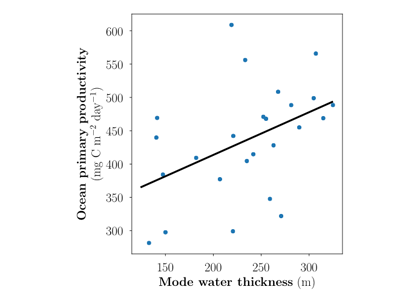

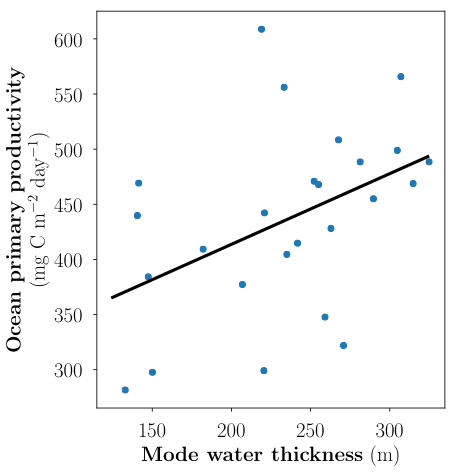

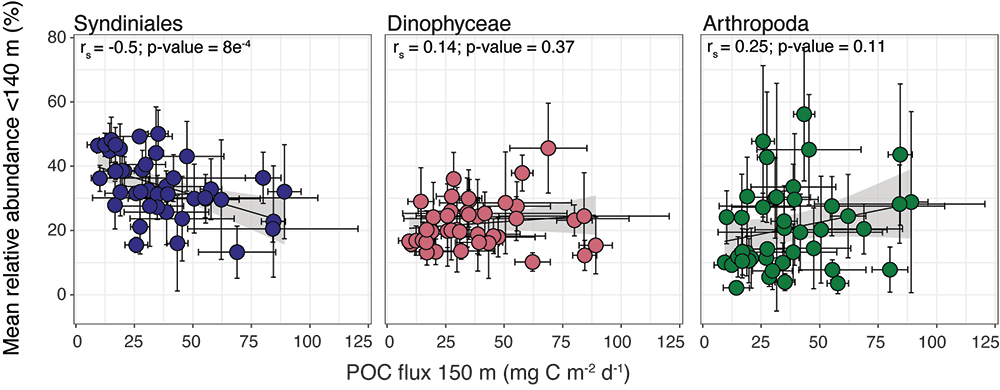

Figure 1. The mean relative abundance of Syndiniales (purple) in the photic zone (<140 m) is negatively correlated with particulate organic carbon (POC) flux at 150 m (p-value < 0.001). Similar correlations are not significant (p-values > 0.05) for other major 18S taxonomic groups, like Dinophyceae (red) and Arthropoda (green).

In a recent study published in ISME Communications, authors analyzed an 18S rRNA gene metabarcoding dataset from the Bermuda Atlantic Time-series Study (BATS) site that included 4 years (2016-2019) and twelve depths (1-1000 m). Syndiniales were the most dominant 18S group at BATS, present throughout the photic and aphotic zones. These parasites were prominent in species networks constructed with 18S sequence data, with significant associations with dinoflagellates and copepods in the surface, and with radiolarians in the aphotic zone. In addition, Syndiniales were the only major 18S group to be significantly (and negatively) correlated to particulate carbon flux (at 150 m), which was estimated from sediment trap data collected concurrently at BATS (Figure 1). This is in situ evidence of flux attenuation among Syndiniales, as they recycle host carbon that would otherwise transfer up to larger organisms (e.g., via grazing). Lastly, authors found 19% of the Syndiniales community is linked between photic and aphotic zones, indicating that parasites are sinking on particles and/or are recirculated via diel vertical migration. Overall, these findings elevate the role of Syndiniales in microbial food webs and further emphasize the importance in quantifying parasite-host dynamics to inform ocean carbon models.

Authors

Sean Anderson (University of New Hampshire / Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Leocadio Blanco-Bercial (Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences / Arizona State University)

Craig Carlson (University of California, Santa Barbara)

Elizabeth Harvey (University of New Hampshire)