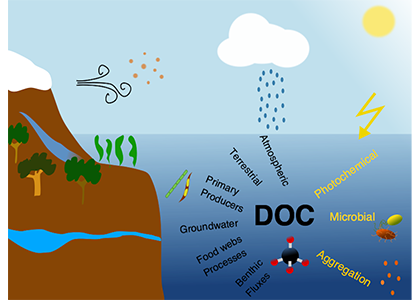

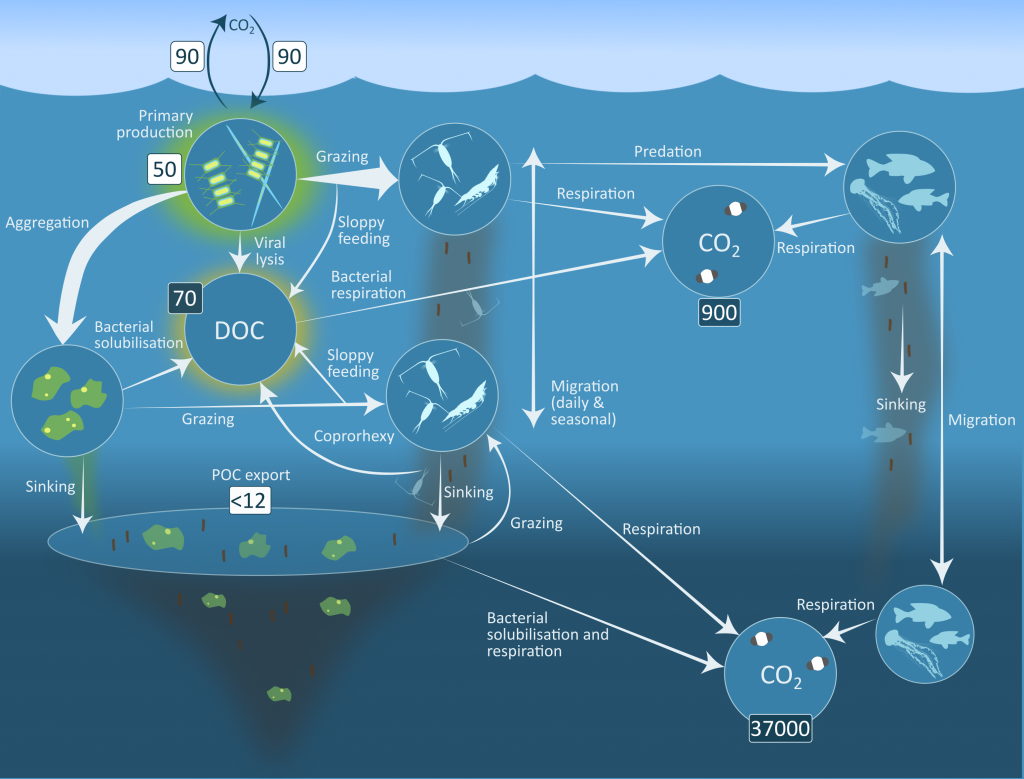

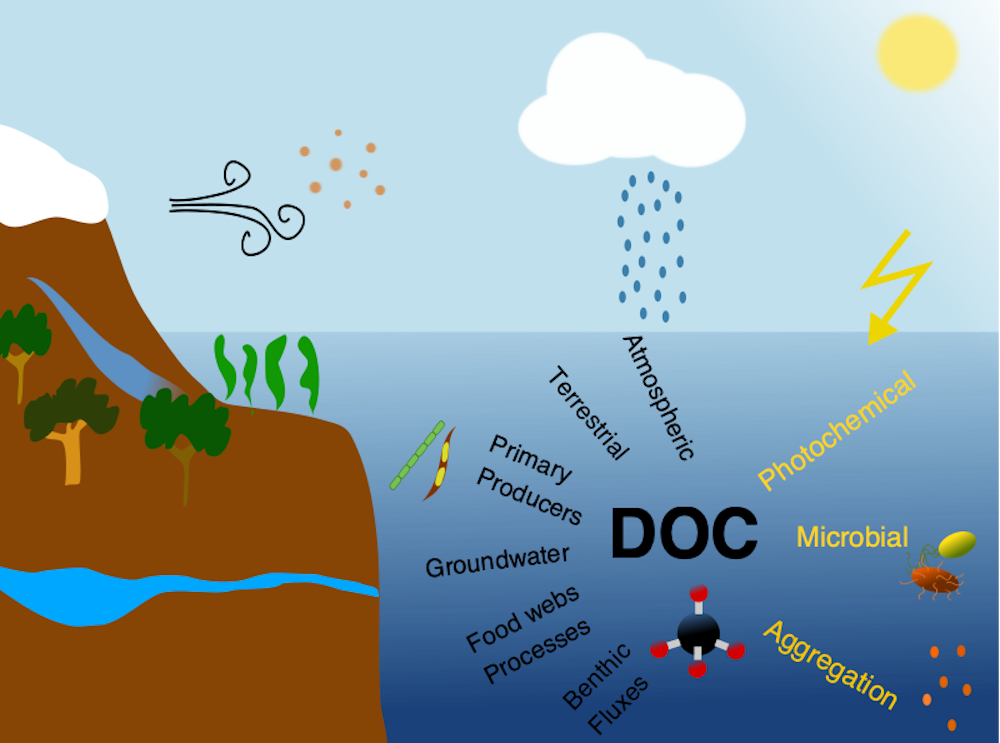

The dissolved organic carbon (DOC) pool is vital for the functioning of marine ecosystems. DOC fuels marine food webs and is a cornerstone of the earth’s carbon cycle. As one of the largest pools of organic matter on the planet, disruptions to marine DOC cycling driven by climate and environmental global changes can impact air-sea CO2 exchange, with the added potential for feedbacks on Earth’s climate system.

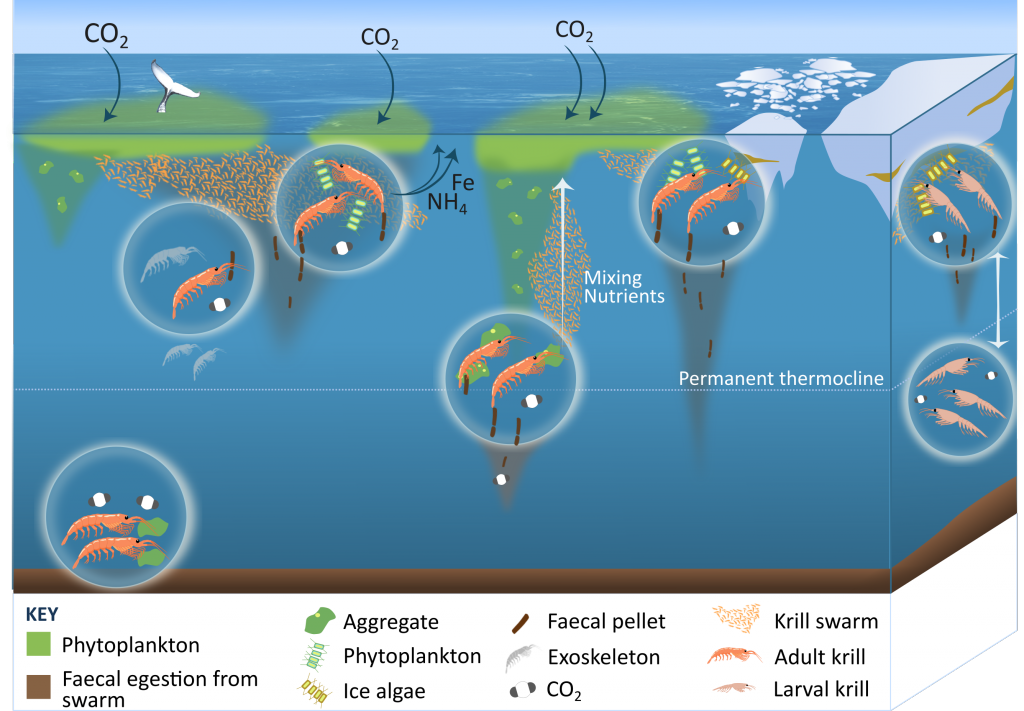

Figure 1. Simplified view of major dissolved organic carbon (DOC) sources (black text) and sinks (yellow text) in the ocean.

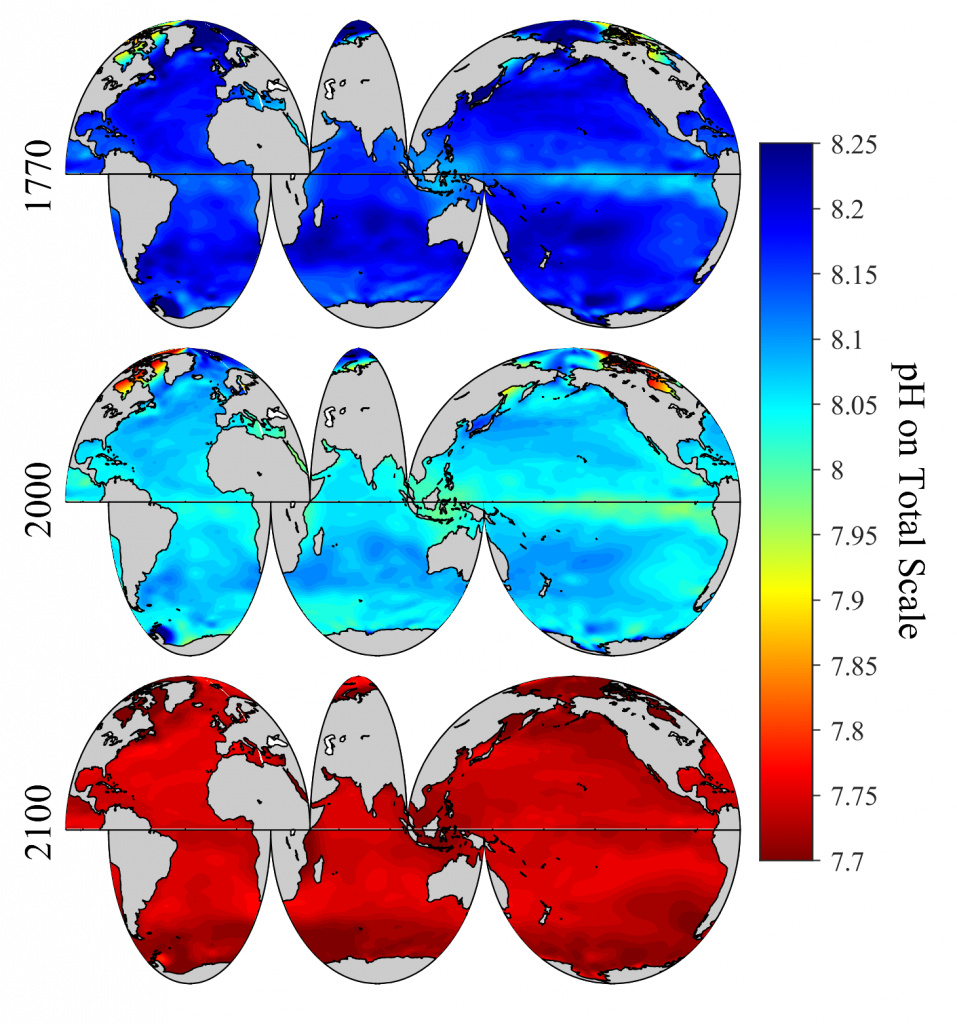

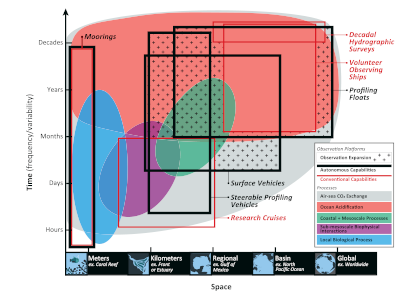

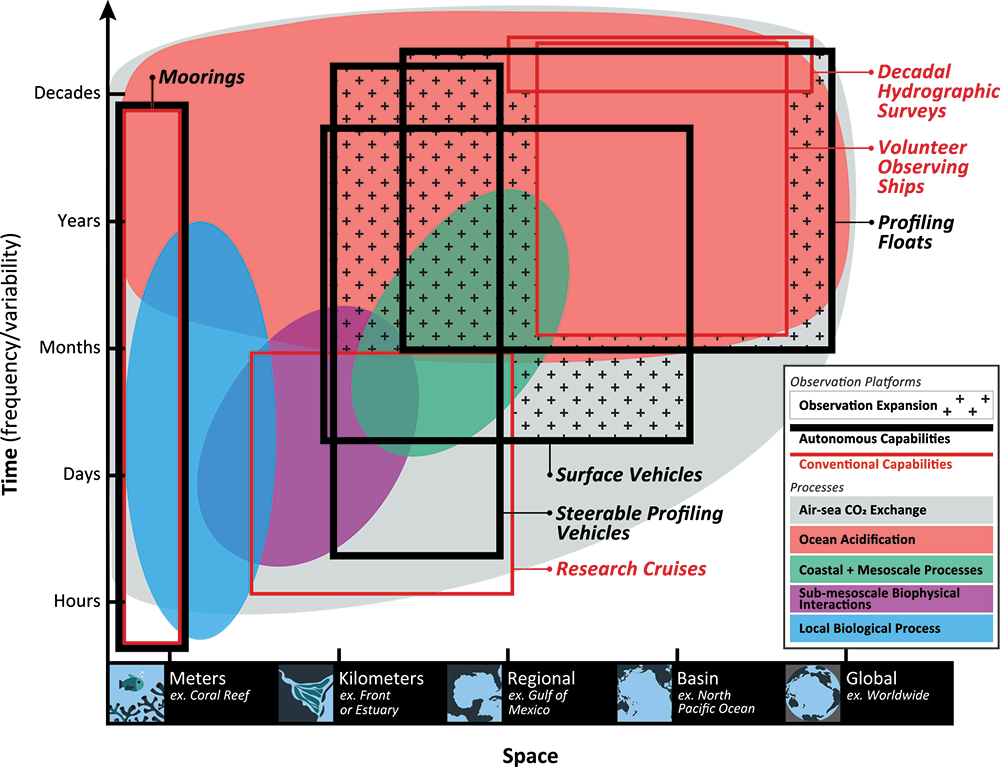

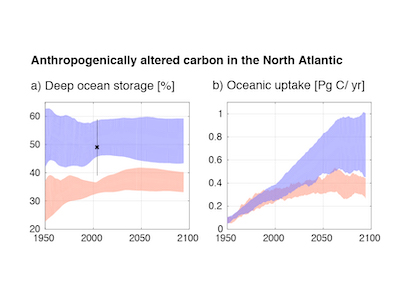

Since DOC cycling involves multiple processes acting concurrently over a range of time and space scales, it is especially challenging to characterize and quantify the influence of global change. In a recent review paper published in Frontiers in Marine Science, the authors synthesize impacts of global change-related stressors on DOC cycling such as ocean warming, stratification, acidification, deoxygenation, glacial and sea ice melting, inflow from rivers, ocean circulation and upwelling, and atmospheric deposition. While ocean warming and acidification are projected to stimulate DOC production and degradation, in most regions, the outcomes for other key climate stressors are less clear, with much more regional variation. This synthesis helps advance our understanding of how global change will affect the DOC pool in the future ocean, but also highlights important research gaps that need to be explored. These gaps include for example a need for studies that allow to understand the adaptation of degradation/production pathways to global change stressors, and their cumulative impacts (e.g. temperature with acidification).

Authors:

C. Lønborg (Aarhus University)

C. Carreira (CESAM, Universidade de Aveiro)

Tim Jickells (University of East Anglia)

X.A. Álvarez-Salgado (CSIC, Instituto de Investigacións Mariñas)