Marine food webs and biogeochemical cycles react sensitively to increases in carbon dioxide (CO2) and associated ocean acidification, but the effects are far more complex than previously thought. A comprehensive study published in Nature Climate Change by a team of researchers from GEOMAR dove deep into the impacts of ocean acidification on marine biota and biogeochemical cycling. The authors combined data from five large-scale field experiments with natural plankton communities to investigate how carbon cycling and export respond to ocean acidification.

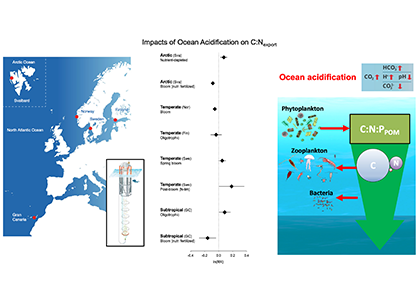

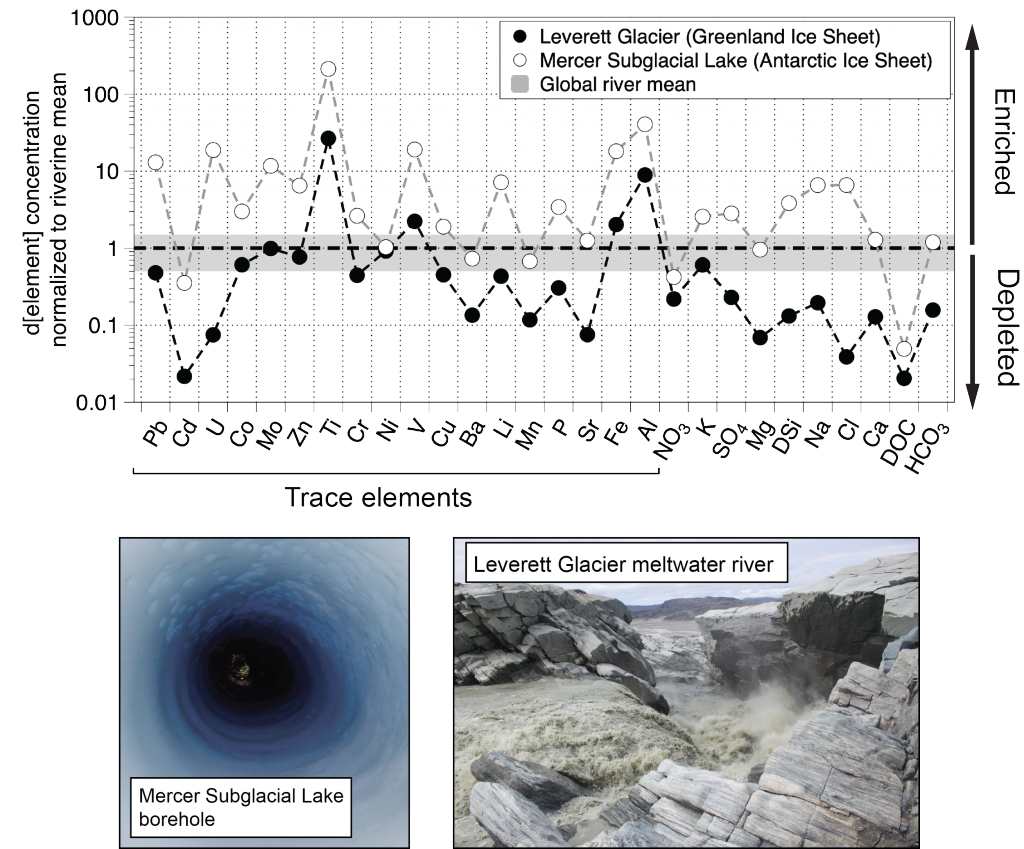

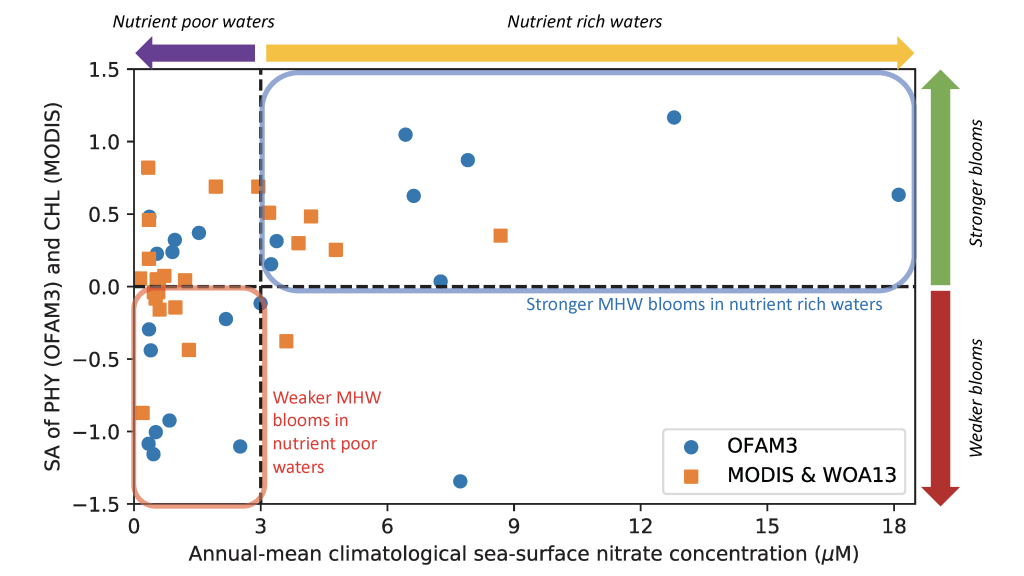

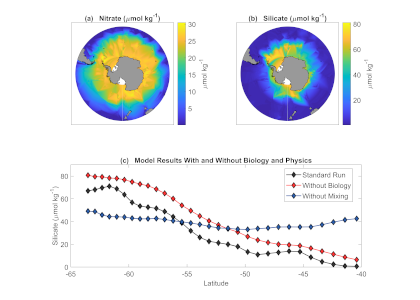

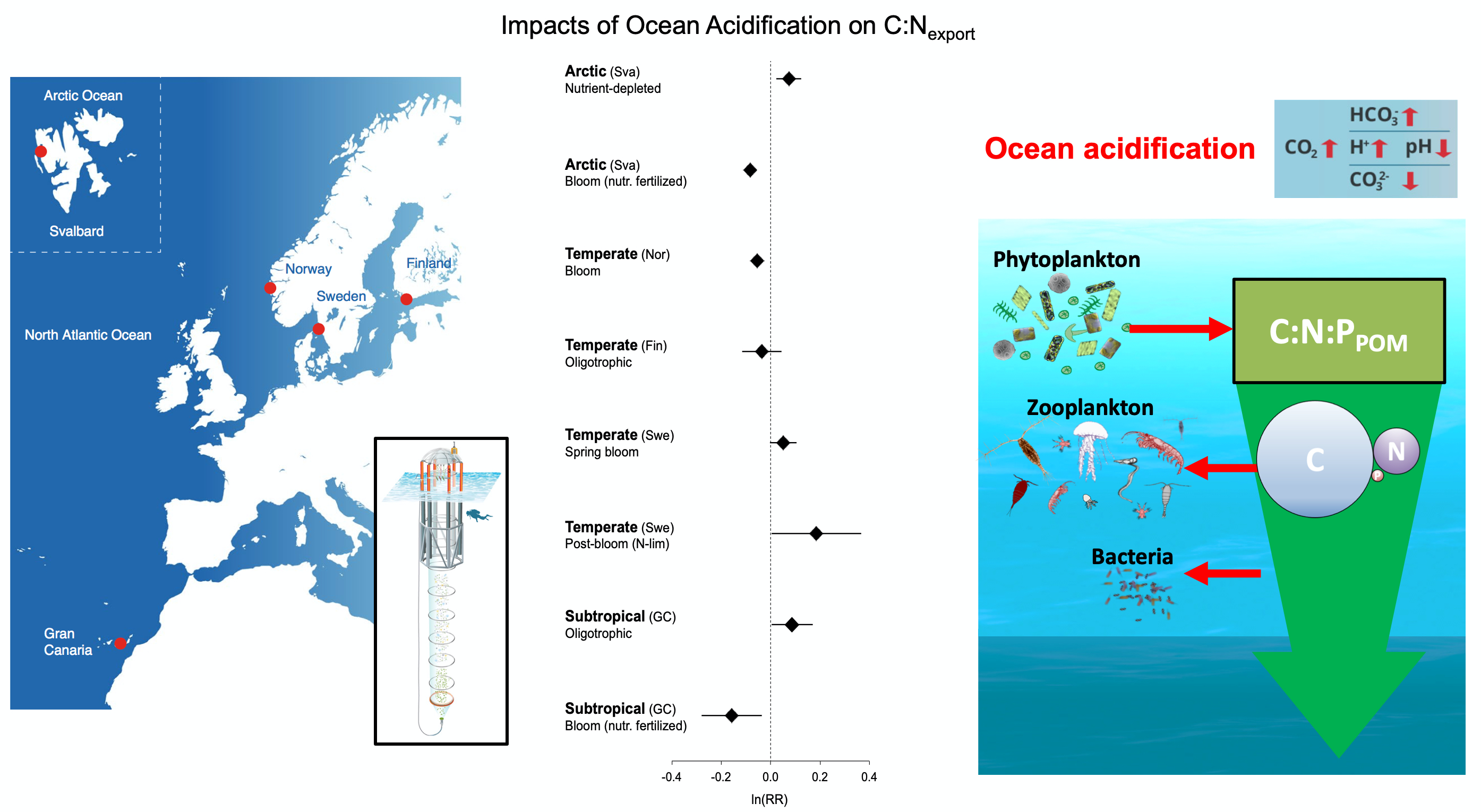

The biological pump is a key mechanism in transferring carbon to the deep ocean and contributes significantly to the oceans’ function as a carbon sink. The carbon-to-nitrogen ratio of sinking biogenic particles, here termed (C:Nexport), determines the amount of carbon that is transported from the euphotic zone to the ocean interior per unit nutrient, thereby controlling the efficiency of the biological pump. The authors demonstrate for the first time that ocean acidification can change the elemental composition of organic matter export, thereby potentially altering the biological pump and carbon sequestration in a future ocean (Figure 1).

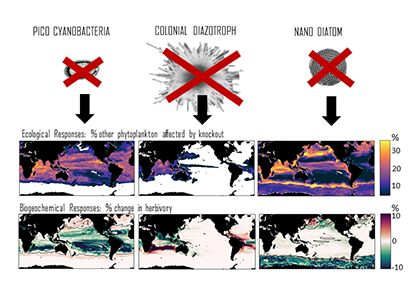

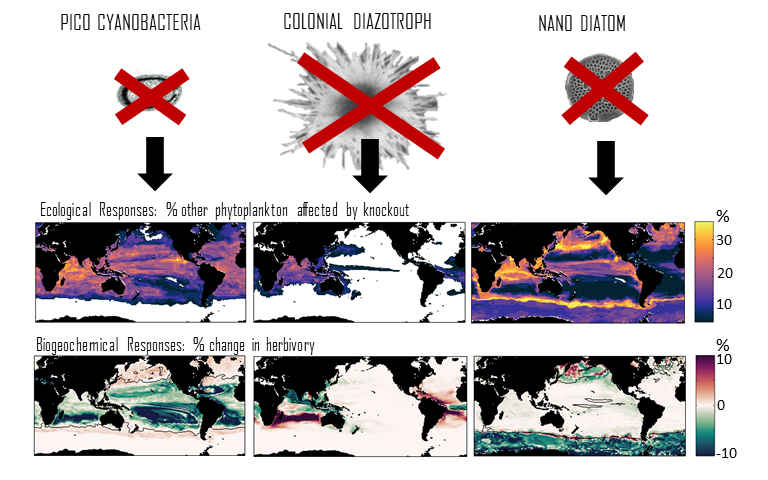

Figure 1: Until now, the common assumption is that changes in C:N (and biogeochemistry, in general) are mainly driven by phytoplankton. In a series of in situ mesocosm experiments in different biomes (left), Taucher et al., (2020) found distinct impacts of ocean acidification on the C:N ratio of sinking organic matter (middle). By linking these observations to analysis of plankton community composition, the authors found a key role of heterotrophic processes in controlling the response of C:N to OA, particularly by altering the quality and carbon content of sinking organic matter within the biological pump (right).

Surprisingly, the observed responses were highly variable: C:Nexport increased or decreased significantly with increasing CO2, depending on the composition of species and the structure of the food web. The authors found that heterotrophic processes driven by bacteria and zooplankton play a key role in controlling the response of C:Nexport to ocean acidification. This contradicts the widespread paradigm that primary producers are the principal driver of biogeochemical responses to ocean change.

Considering that such diverse pathways, by which planktonic food webs shape the elemental composition and biogeochemical cycling of organic matter, are not represented in state-of-the-art earth system models, these findings also raise the question: Are currently able to predict the large-scale consequences of ocean acidification with any certainty?

Authors:

Jan Taucher (GEOMAR, Kiel, Germany)

Tim Boxhammer (GEOMAR, Kiel, Germany)

Lennart T. Bach (University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia)

Allanah J. Paul (GEOMAR, Kiel, Germany)

Markus Schartau (GEOMAR, Kiel, Germany)

Paul Stange (GEOMAR, Kiel, Germany)

Ulf Riebesell (GEOMAR, Kiel, Germany)