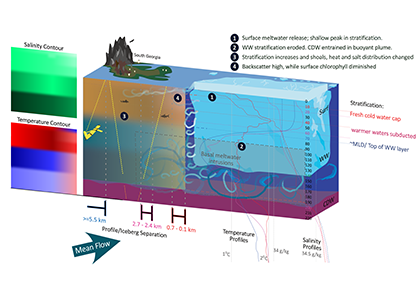

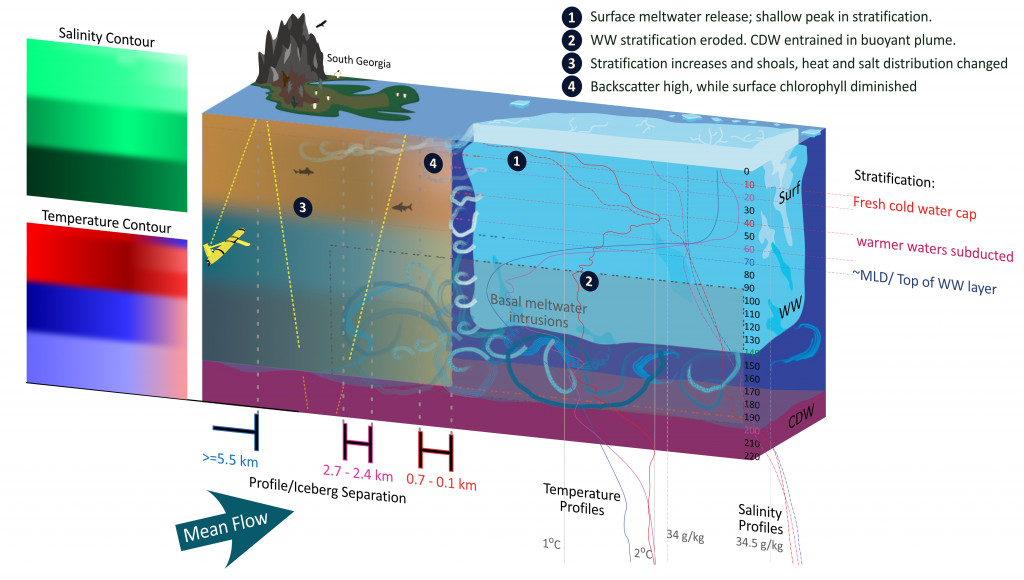

Iceberg meltwater induces mixing which erodes upper-ocean layers. This supplies nutrients, both released from the iceberg and entrained from deeper waters, to surface waters which stimulates phytoplankton growth.

Meltwater from the base, sidewalls and surface of giant icebergs influences upper ocean stratification and mixing. Containing a substantial micro-nutrient load, (incorporating nutrient-rich deep waters along with mineral-rich particles, such as iron and silica, from the melting iceberg), this meltwater is thought to relieve nutrient limitation in surface ecosystems, impacting ocean biological productivity and carbon drawdown. A recent paper in Nature Geoscience provides high-resolution glider measurements right next to giant iceberg A-68A; elucidating the effects of meltwater on water mass modification and near-surface productivity.

The number of calving icebergs is expected to increase in the near future, however the impact of iceberg meltwater on the hydrography, circulation and mixing of the upper ocean is poorly quantified. Understanding the complex physical and biological impacts on the ocean waters through which icebergs transit is difficult to represent in global ocean models, precipitating complexity in prediction of future ocean circulation and the health of Antarctic ecosystems.

Authors

Natasha S Lucas (British Antarctic Survey)

J. Alexander Brearley (British Antarctic Survey)

Katharine R Hendry (British Antarctic Survey)

Theo Spira (University of Gothenburg)

Anne Braakmann-Folgmann (The Arctic University of Norway)

E. Povl Abrahamsen (British Antarctic Survey)

Michael P Meredith (British Antarctic Survey)

Geraint A Tarling (British Antarctic Survey)

Social media:

@krhendry.bsky.social

@TashaOcean

www.bas.ac.uk

@britishantarcticsurvey

@bangor_university

@bangor.sos

@polarwomen @womeninoceanscience

#TashaGoesSouth #PolarResearch #SouthernOcean #AgulhasII #WomenInPhysics #WomenInScience #ExperimentalPhysics #Oceanography #Antarctica

A little extra background:

Roughly a quarter the size of Wales at 5800 square kilometres, A-68A was the biggest iceberg on Earth when it calved from the Larsen-C Ice Shelf in 2017. It arrived at South Georgia as the sixth largest giant iceberg on record. A-68A deposited an estimated 152 billion tonnes of nutrient-rich fresh water, equivalent to 61 million Olympic sized swimming pools, and 27 times the annual freshwater outflow from South Georgia, into the seas around this sub-Antarctic island during the three months of this glider survey.

Ocean gliders are a type of small, robotic underwater vehicle that use density differences, or buoyancy, to move up and down through the water column with wings to create lift, propelling it forward. While ‘flying’ through the water, from the surface to 1 km in depth, the gliders’ sensors measure the water’s properties. The glider surfaces at regular intervals to check its position by GPS, transmit sparse data back to the UK using a satellite phone system, and check for new instructions on where to go and what instruments to turn on.

Research Briefing https://rdcu.be/eg39r