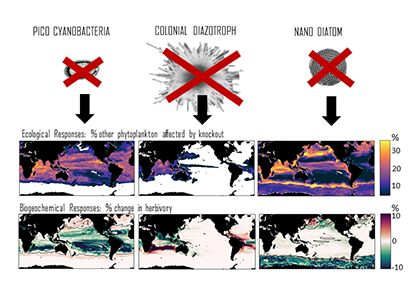

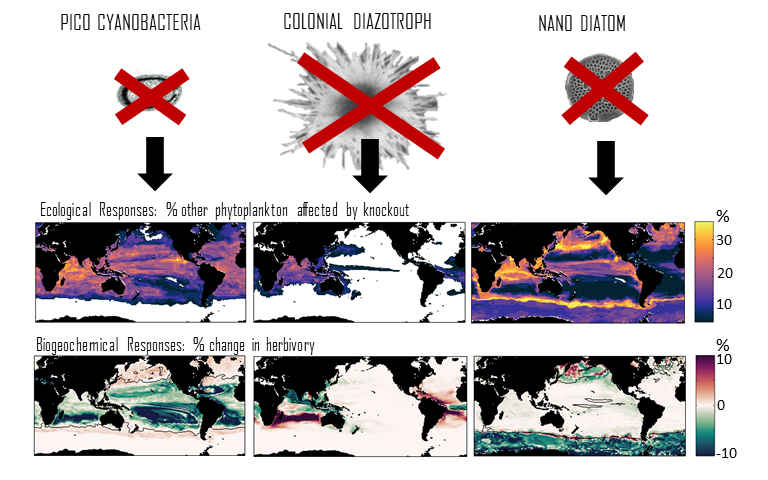

Climate change impacts on the ocean such as warming, altered nutrient supply, and acidification will lead to significant rearrangement of phytoplankton communities, with the potential for some phytoplankton species to become extinct, especially at the regional level. This leads to the question: What are phytoplankton species’ redundancy levels from ecological and biogeochemical standpoints—i.e. will other species be able to fill the functional ecological and/or biogeochemical roles of the extinct species? Authors of a paper published recently in Global Change Biology explored these ideas using a global three-dimensional computer model with diverse planktonic communities, in which single phytoplankton types were partially or fully eliminated. Complex trophic interactions such as decreased abundance of a predator’s predator led to unexpected “ripples” through the community structure and in particular, reductions in carbon transfer to higher trophic levels. The impacts of changes in resource utilization extended to regions beyond where the phytoplankton type went extinct. Redundancy appeared lowest for types on the edges of trait space (e.g., smallest) or those with unique competitive strategies. These are responses that laboratory or field studies may not adequately capture. These results suggest that species losses could compound many of the already anticipated outcomes of changing climate in terms of productivity, trophic transfer, and restructuring of planktonic communities. The authors also suggest that a combination of modeling, field, and laboratory studies will be the best path forward for studying functional redundancy in phytoplankton.

Figure caption: Examples of the modelled ecological and biogeochemical responses to the extinction of different phytoplankton species.Figure caption: Examples of the modelled ecological and biogeochemical responses to the extinction of different phytoplankton species.

Authors:

Stephanie Dutkiewicz (Massachusetts Institute of Technology)

Philip W. Boyd (Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania)

Ulf Riebesell (GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel)