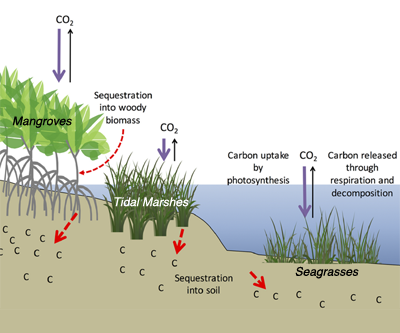

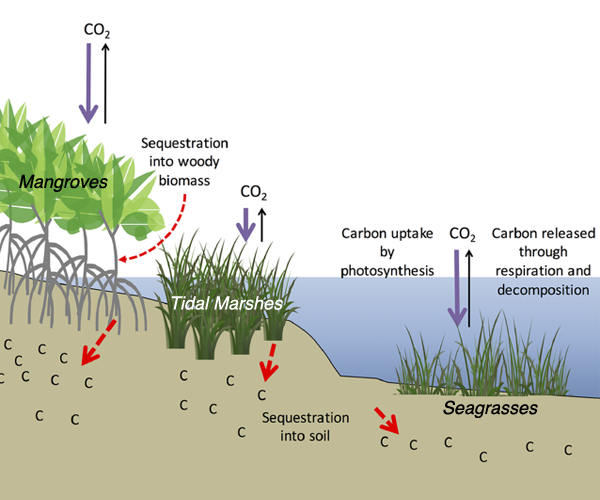

The Gulf of Mexico (GoM) is an important global hotspot that comprises over 2.1615 million hectares of blue carbon habitats, including mangroves, seagrasses, and salt marshes, which collectively store 480.5 Tg of organic carbon (Corg) just in the upper 1 meter of sediment. Some of these important areas of carbon sequestration are protected or conserved, but much of the area is vulnerable, as 69 million people (US and Mexico) live within 50 miles of these blue carbon habitats, so the potential for development and subsequent habitat loss is high. In a recent study published in Science of the Total Environment, the estuaries around the GoM were delineated to determine areal extent and associated carbon stocks for all three habitats.

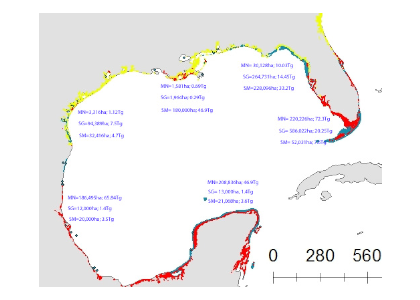

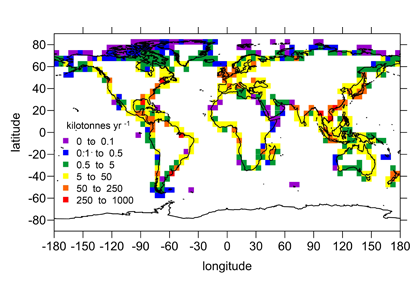

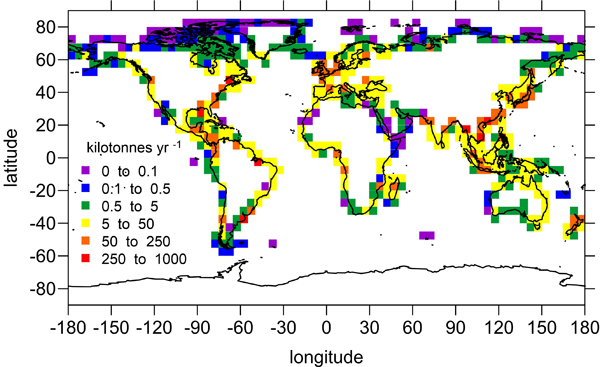

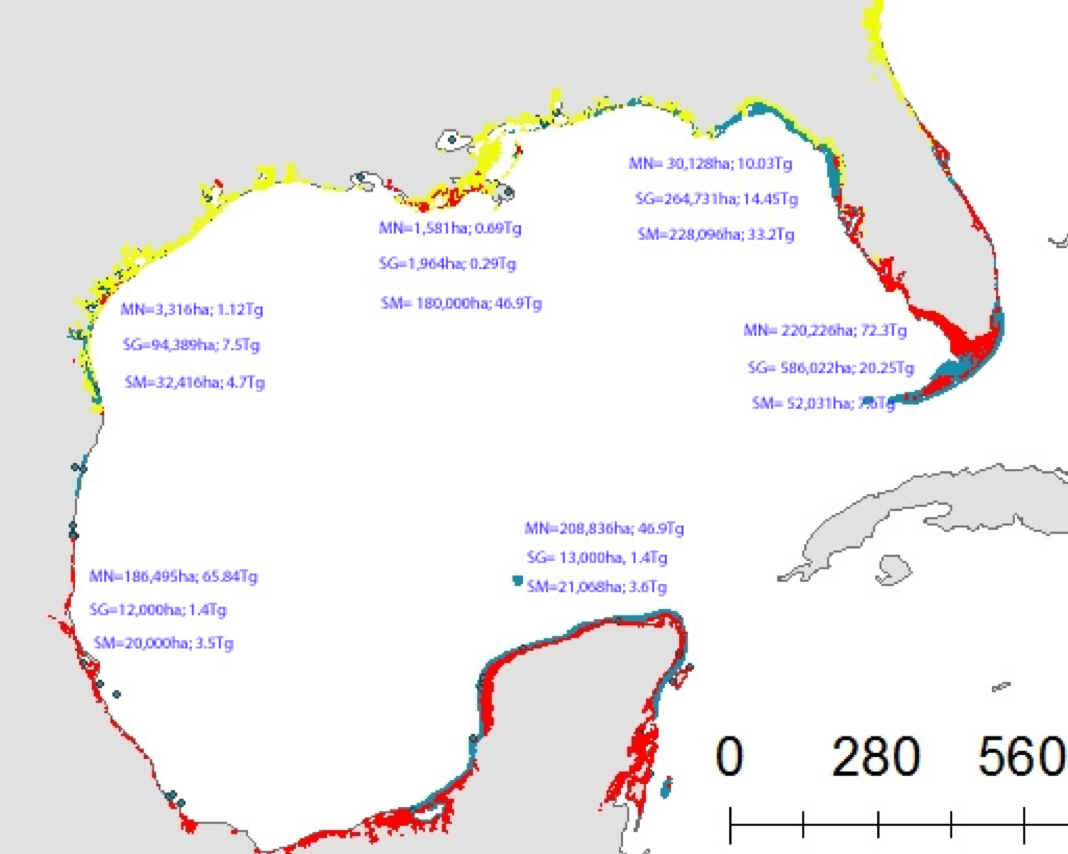

Figure 1: Map of blue carbon extent and stock for six sub-regions in the Gulf of Mexico estuaries and the Florida Shelf. The areal extent in hectares (ha) and associated organic carbon (Corg) stock in Tg is listed for each blue carbon system (MN = mangroves, SG = seagrass, SM = saltmarsh) in each sub-region. The underlying blue carbon map shows the distribution of mangroves (red), saltmarsh (yellow), and seagrass (blue) (used with permission from Chmura and Short, 2015).

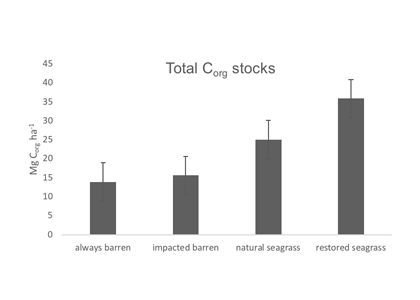

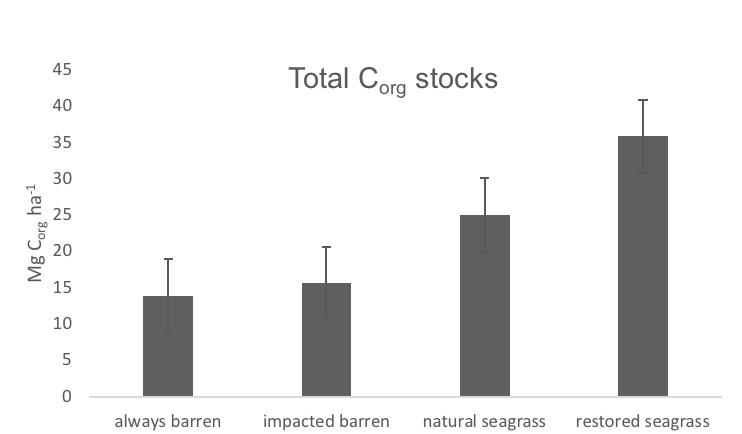

Of the GoM blue carbon systems studied, mangroves sequester the most carbon, storing nearly 200 Tg Corg over 650,482 ha (Figure 1). Seagrass is ubiquitous throughout the GoM basin, spanning over 1 million ha and storing 184 Tg Corg, Salt marshes, which are predominantly found in the northwestern quadrant of the GoM account for just under 100 Tg Corg. In addition to presenting these updated blue carbon stock estimates for the GoM, this study estimates anthropogenic impacts on GoM blue carbon storage and compares GoM vs. Atlantic shoreline blue carbon habitat stocks and extents.

Authors:

Anitra L. Thorhaug (Yale University)

Helen M. Poulos (Wesleyan University)

Jorge López-Portillo (Instituto de Ecología Mexico)

Jordan Barr (Elder Research)

Ana Laura Lara-Domínguez (Instituto de Ecología Mexico)

Tim C. Ku (Wesleyan University)

Graeme P.Berlyn (Yale University