Around the world, human-altered shorelines change sediment inputs to estuaries and coastal waters, altering water clarity, especially in areas of dense human population. The Chesapeake Bay estuary is recovering from historically high nutrient and sediment inputs, but water clarity improvement has been ambiguous. Long-term trends show increasing water clarity in terms of deepening light attenuation depth, yet degrading clarity in terms of shallowing Secchi depth over time. High water clarity is needed to support seagrass meadows, which act as nursery habitats for commercially important fish species such as striped bass. How are these opposing water clarity trends possible?

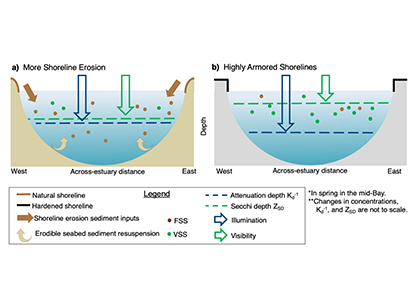

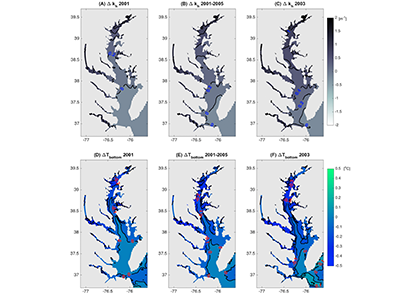

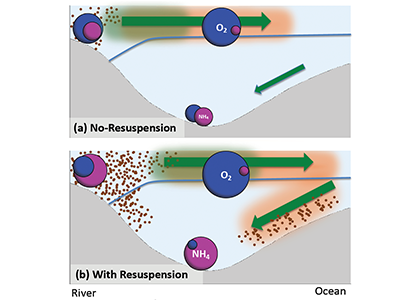

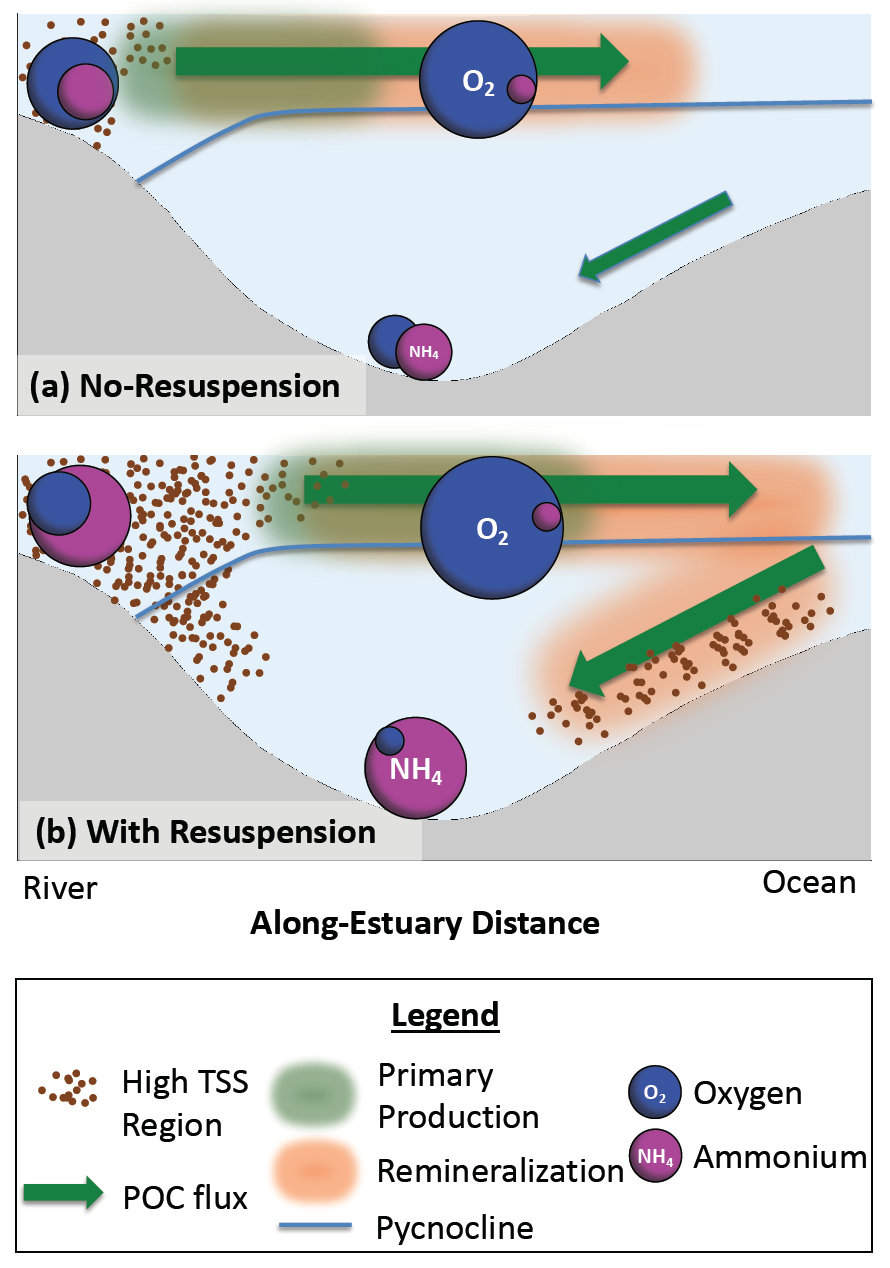

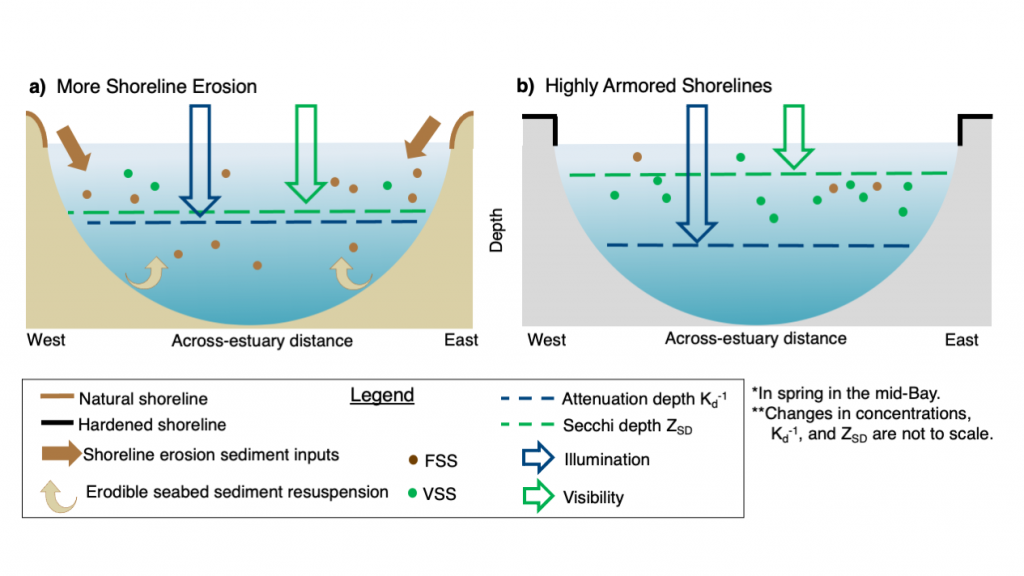

In a recent paper published in Science of the Total Environment, researchers performed experiments with a coupled hydrodynamic-biogeochemical model to test a simulated Chesapeake Bay under realistic conditions, more shoreline erosion, and highly armored shorelines. Comparing the two extreme conditions (Figure 1), there was a striking difference between (a) an estuary experiencing more shoreline erosion and greater resuspension versus (b) a highly armored estuary with decreased resuspension. Reduced erosion yielded improved water clarity in terms of light attenuation depth, but a shallower Secchi depth (reduced visibility). In estuaries, reducing sediment inputs is often proposed as a strategy for improving water quality. This study shows that, under certain conditions in a productive estuary, reduced sediments can have unintended secondary effects on water clarity due to enhanced production of organic particles. This study also highlights the need to consider other sediment sources in addition to rivers, such as seabed resuspension and shoreline erosion, especially at times and locations of low river input.

Figure 1. Schematic of how shoreline armoring causes deepening light attenuation depth (navy) yet shallowing Secchi depth (green) during the spring growing season in the mid-bay central channel.

Authors:

Jessica S. Turner

Pierre St-Laurent

Marjorie A. M. Friedrichs

Carl T. Friedrichs

(all Virginia Institute of Marine Science)