Only about half of human-made CO2 emissions remain in the atmosphere and drive global warming. The other half has so far been said to be taken up in roughly equal amounts by the biosphere on land and by physical-chemical processes in the ocean. In equal amounts?

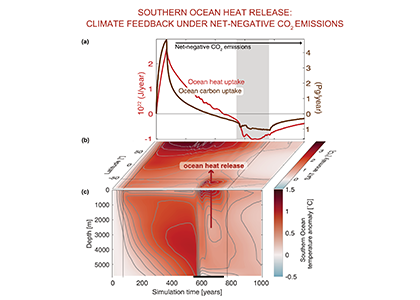

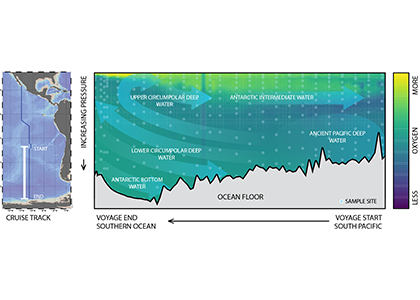

In a new assessment, Friedlingstein et al. reassess the various components of the Global Carbon Budget. Major changes were suggested for the land and ocean sinks. For the land, the prior assumption of a preindustrial land-cover in the Dynamic Global Vegetation Models (DGVM) led to an overestimation of the natural land sink in previous studies. The land sink is further revised downwards by accounting for an anthropogenic perturbation of lateral carbon export to the ocean. For the ocean, adjustments were made for the known underestimation of the ocean sink from Global Ocean Biogeochemical Models and the cool and salty skin effect in surface fCO2-observation-based estimates. As a result, the ocean is now estimated to have taken up 29% of anthropogenic CO2 emissions in the last decade 2015-2024, while the land sink has taken up 21%. In this revised estimate with virtually no budget imbalance over the last decade and no significant trend in the budget imbalance since 1960, climate-driven impacts on the natural sinks are quantified: Land and ocean sinks would be 25% and 7% higher, respectively, without this carbon-climate feedback. Since 1960, the carbon-climate feedback has already contributed 8 ppm (8%) to the rise in atmospheric CO2 concentration.

The negative imprints of earth system changes (e.g., warming, droughts, changes in wind patterns and ocean circulation, etc.) on these important carbon sinks is worrisome and is expected to intensify as warming continues. The most effective way to protect these sinks is to drastically reduce CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and land-use changes, ultimately to net zero.

Authors

Judith Hauck (Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, University of Bremen)

Peter Landschützer (VLIZ)

Corinne Le Quéré (University of East Anglia)

Pierre Friedlingstein (University of Exeter)

Bluesky: @pfriedling @jhauck @clequere