Thorium-234 (234Th), a naturally radioactive element present in nature, is one of the most actively used tracers in oceanography. 234Th is widely used to study the removal rate of material on sinking particles from the upper ocean, known as “scavenging,” and for determining the downward flux of carbon. Starting in 1969, ocean measurements of the 234Th temporal distribution in the hydrologic cycle comprise an indispensable component of oceanographic expeditions. However, even after five decades and extensive use of 234Th to understand natural aquatic processes, there are major gaps in this tool, no unified compilation of 234Th measurements and no centralized source for 234Th data.

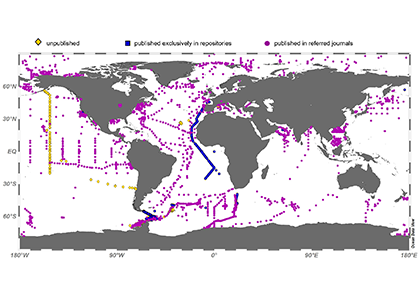

A new study aims to fill these gaps with a comprehensive global oceanic compilation of 234Th measurements in a single open-access, long-term, and dynamic repository. They collated over 50 years of results from researchers and laboratories, 379 oceanographic expeditions, and more than 56 600 234Th data points from over 5000 locations spanning every ocean. These data are archived on PANGAEA® (Ceballos-Romero et al., 2021, see references below).

This paper introduces the dataset in context via informative and descriptive graphics and a broad overview of the data sets, with potential uses for future studies. A historical review of 50 years of the 234Th technique is included also, covering four well-distinguished eras that are marked by four seminal publications that changed the course of the 234Th technique and impact on oceanography.

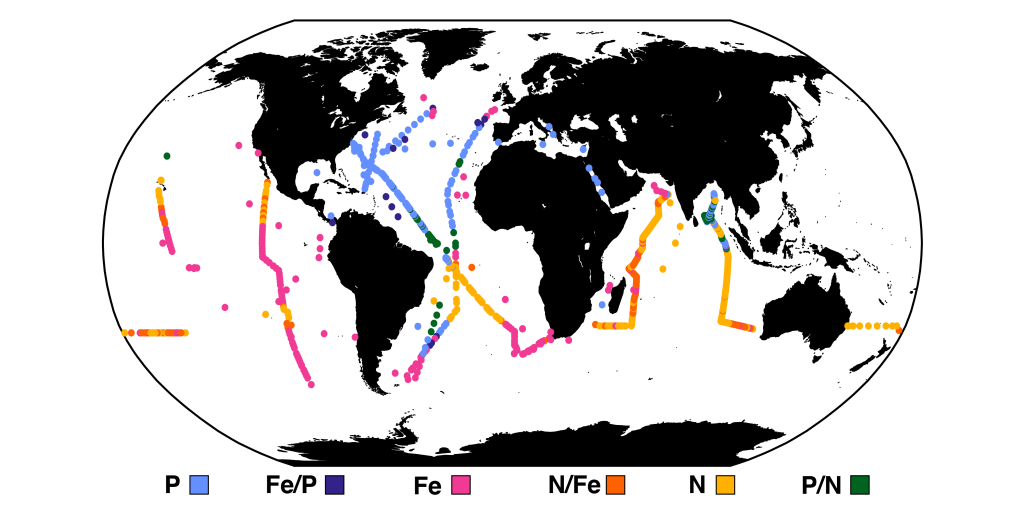

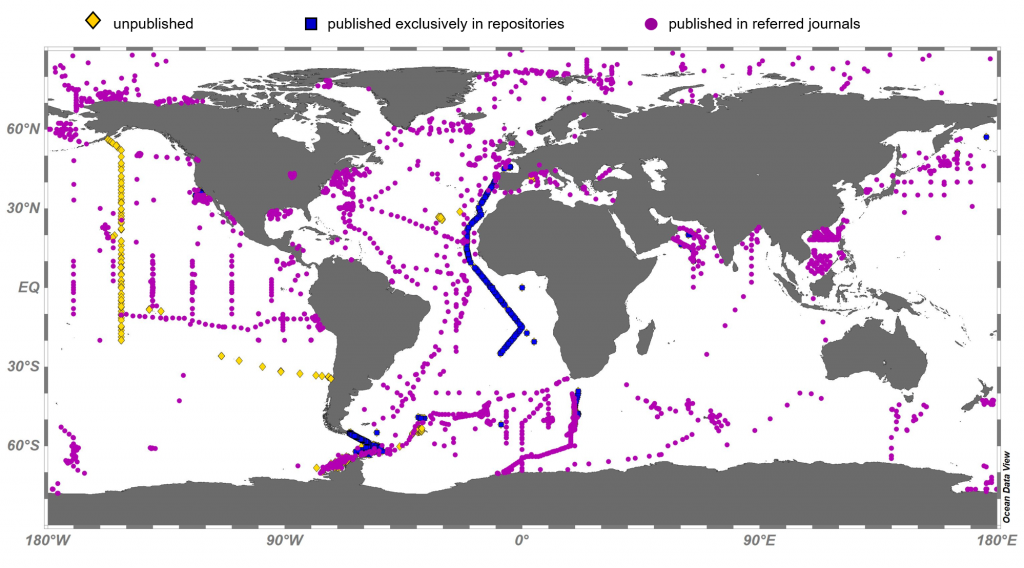

Map showing the distribution of sampling stations cataloged as i) unpublished (yellow diamonds), ii) published exclusively in repositories (blue square), and iii) published in referred journals (magenta circles).

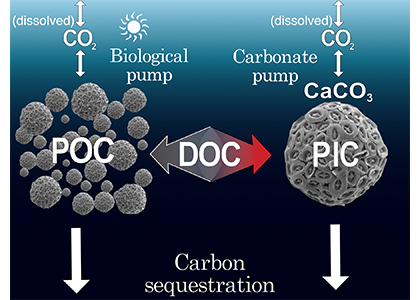

This compilation is especially relevant to present and future investigations of the biological carbon pump (BP), which transports carbon to the deep ocean and regulates atmospheric CO2 levels. In the last few decades, scientists have made considerable progress on unraveling the behavior of the BP. However, many questions on how the mechanisms function and shape carbon dynamics and the ocean carbon cycle remain unknown. The authors emphasize that many analyses of BP processes could benefit from utilizing 234Th data. The authors list a number of applications that could derive from this impressive data set, such as establishing the distribution of the probability of 234Th reaching equilibrium (or not) with its parent at 100 m. This distribution allows extracting i) the number of data points in the compilation that could be used to evaluate processes in the upper ocean (e.g., export flux and export efficiency) or ii) scavenging rates of trace metals or particle sinking velocities using “deficit” ratios, as well as those that could be used to study processes such as particle remineralizations by using the “excess” ratios. This compilation provides a valuable resource to better understand and quantify how the contemporary oceanic carbon uptake functions and how it may change in the future. This tool can be served as a focal point for the 234Th community under the principles of openness and reproducibility.

Authors

Elena Ceballos-Romero (University of Sevilla and WHOI)

Ken O. Buesseler (WHOI)

María Villa-Alfageme (University of Sevilla)

References

Ceballos-Romero, E., Buesseler, K. O. and Villa-Alfageme, M. (2022) ‘Revisiting five decades of 234Th data: a comprehensive global oceanic compilation’, Earth System Science Data, 14(6), pp. 2639–2679. doi: 10.5194/essd-14-2639-2022.

Ceballos-Romero, E., Buesseler, K. O., Muñoz-Nevado, C., and Villa-Alfageme, M. (2021) ‘More than 50 years of Th-234 data: a comprehensive global oceanic compilation‘, PANGAEA. doi: 10.1594/PANGAEA.918125.