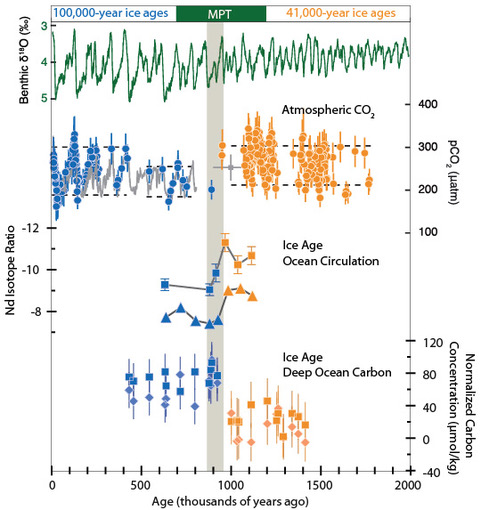

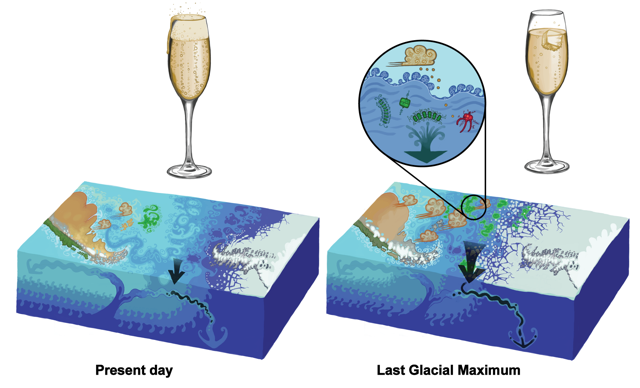

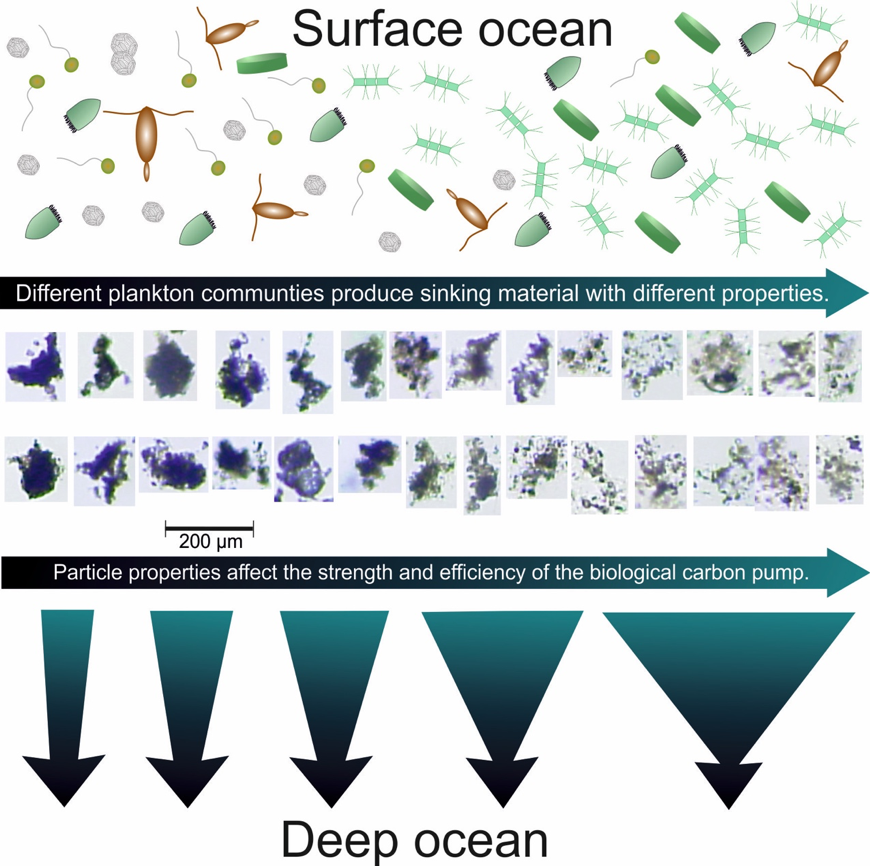

Plankton in the surface ocean convert CO2 into organic biomass thereby fueling marine food webs. Part of this organic biomass sinks down into the deep ocean, where the surface-derived organic carbon, or respired CO2, is locked in for decades to millennia. Without the biological carbon pump, atmospheric CO2 would be ~200 ppm higher than it is today. We know that ecological processes in the surface ocean plankton communities have a paramount importance on the efficiency of the biological carbon pump. Unfortunately, however, the mechanisms how ecology determines sinking fluxes are poorly understood.

A recent study in Global Biogeochemical Cycles used large-scale in situ mesocosms to explore how the ecological interplay within plankton communities affects the downward flux of organic material. Organic biomass tends to sink faster when produced by smaller organisms because the sinking material they generate forms dense aggregates. Conversely, larger organisms produce relatively porous particles that sink more slowly.

Figure: Flow chart illustrating how plankton community structure affects the properties of sinking organic particles and ultimately the strength and efficiency of the biological carbon pump. The thick arrows at the bottom indicate that flux attenuation depends on the properties of particulate matter formed in the surface ocean. For example, slow-sinking porous aggregates containing large amounts of easily degradable organic substances will decay faster (right side) than dense aggregates of more refractory organic matter (left side).

The key finding of this study was the unexpectedly large influence that plankton community composition has on the degradation rate of sinking organic biomass. In fact, degradation rates changed maximally 15-fold over the course of the study while sinking speed changed only 3-fold. Degradation rate of sinking material, measured in oxygen consumption assays, was quite variable and tended to be higher for more easily degradable fresh organic matter. The rate was lower during harmful algal blooms, which produce toxic substances that inhibit organisms that feed on aggregates thereby reducing degradation rates. These findings are an important step forward as they show that our predictive understanding of the biological carbon pump could be improved substantially when linking degradation rates of sinking material with ecological processes in surface ocean plankton communities.

Authors:

L. T. Bach (University of Tasmania)

P. Stange, J. Taucher, E. P. Achterberg, M. Esposito, U. Riebesell (GEOMAR)

M. Algueró‐Muñiz (Alfred-Wegener-Institut Helmholtz)

H. Horn (NIOZ and Utrecht University)