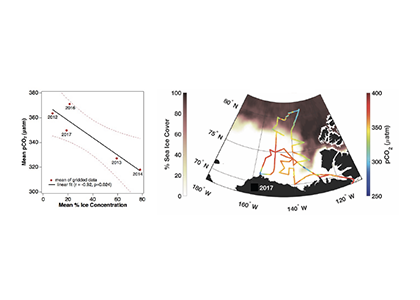

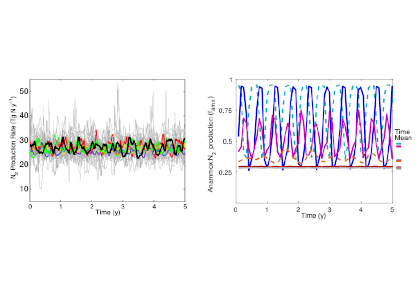

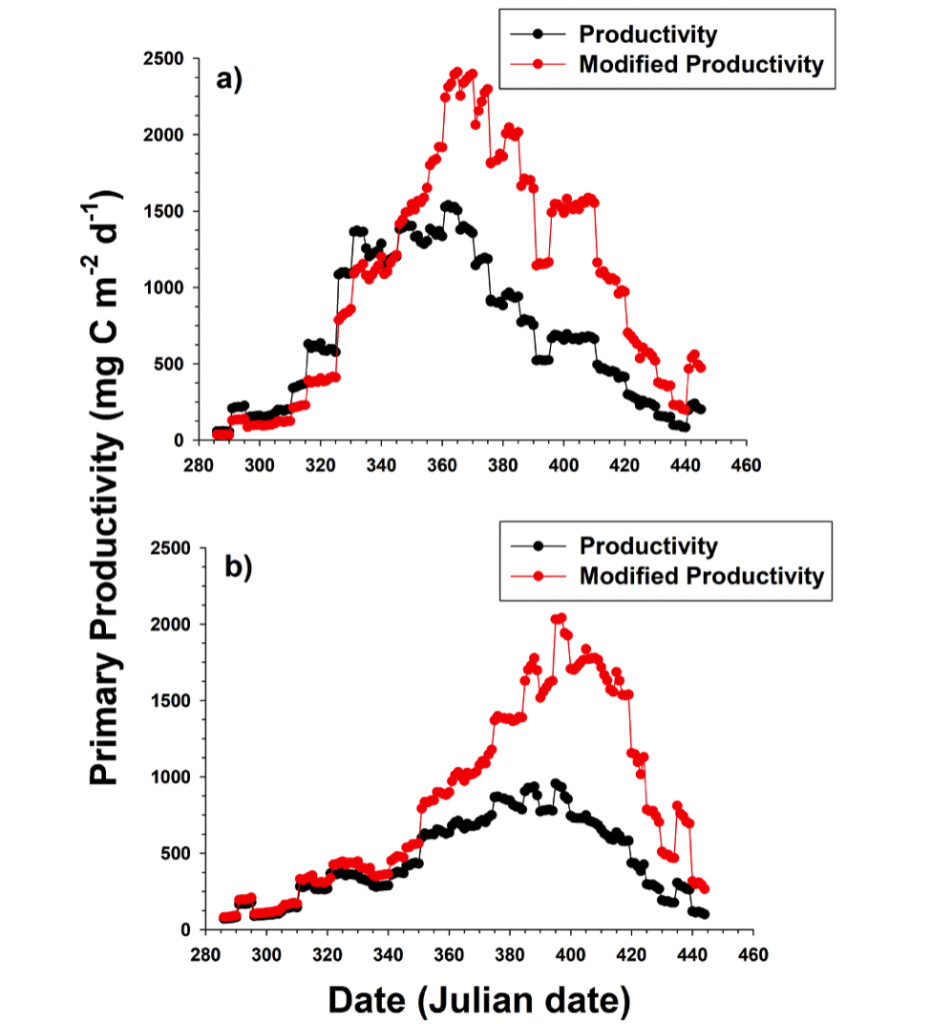

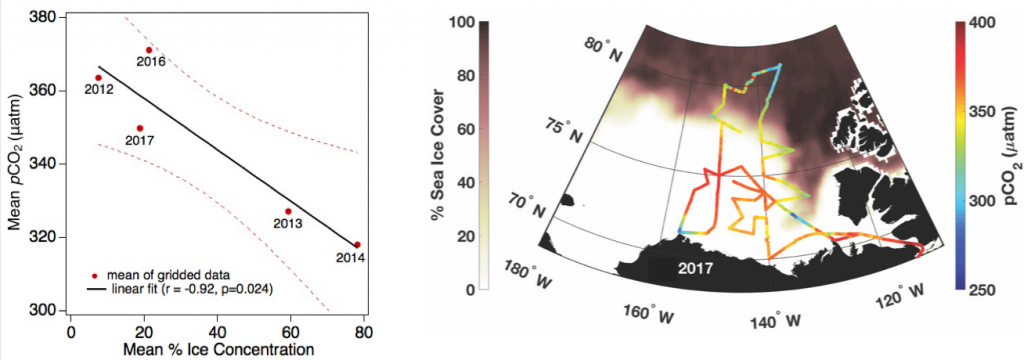

Loss of Arctic Ocean ice cover is altering the carbon cycle in ways that are not well understood. Effectively “popping the top off” the Arctic Ocean, ice loss exposes the sea surface to warming and exchange of CO2 with the atmosphere. These processes are expected to increase CO2 levels in the Arctic Ocean, changing its contribution to the global carbon cycle, but limited data collection in the region has thus far precluded the establishment of a clear relationship between CO2 and ice cover. In a recent study published in Geophysical Research Letters, authors report on observed partial pressure of CO2 (pCO2) trends from several years of data collection in the surface waters of the Canada Basin of the Arctic Ocean. These data show that the pCO2 is higher during years when ice cover is low. Uptake of atmospheric CO2 and heating are the primary sources of the CO2 increase, with only a small counteracting offset from biological production. These processes vary significantly from year to year, masking the likely increase in pCO2 over time. Based on these results, we can expect that, while the Arctic Ocean has thus far been a significant sink for atmospheric CO2, if ice loss continues the uptake of CO2 will diminish in coming years.

Figure caption: Sea surface pCO2 increases with decreasing ice concentration (left), determined using the mean of spatially gridded data. The sea surface pCO2 data were collected on five research cruises on the Canadian icebreaker, CCGS Louis S. St-Laurent, from 2012 to 2017 (shown at right for 2017). The pCO2 levels are indicated by the color along the ship cruise track (right color bar). The dark shading (left color bar) represents sea ice concentration averaged from the daily satellite data collected during the cruise.

Authors:

Michael DeGrandpre (University of Montana-Missoula)

Wiley Evans (Hakai Institute)

Mary-Louise Timmermans (Yale University)

Richard Krishfield (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Bill Williams (Institute of Ocean Sciences)

Michael Steele (University of Washington)