The pelagic brown alga Sargassum forms a habitat that hosts a rich diversity of life, including other algae, crustaceans, fish, turtles, and birds in both the Gulf of Mexico and the area of the Atlantic Ocean known as the Sargasso Sea. However, high abundances of Sargassum have been appearing in the tropical Atlantic, in some cases 3,000 miles away from the Sargasso Sea. This is a new phenomenon. Nearly every year since 2011, thick mats of Sargassum have blanketed the coastlines of many countries in tropical Africa and the Americas. When masses of Sargassum wash ashore, the seaweed rots, attracts insects, and repels beachgoers, with adverse ecological and socioeconomic effects. A new study in Progress in Oceanography sheds light on the mystery.

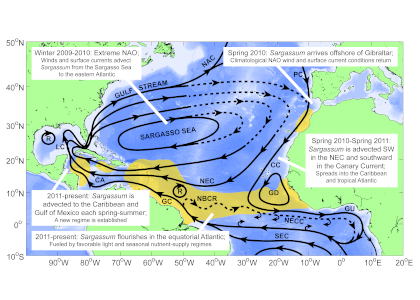

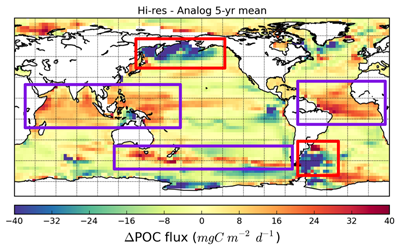

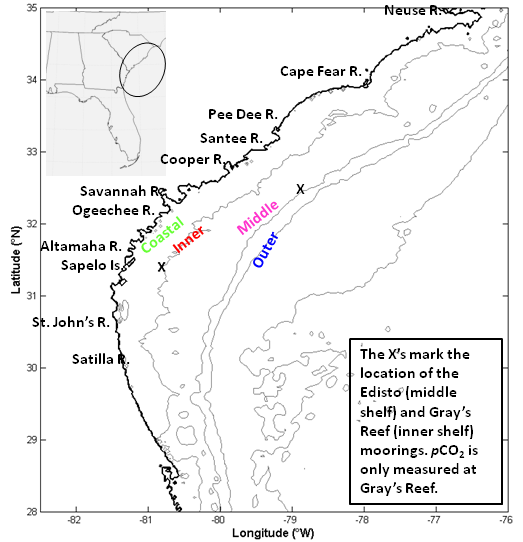

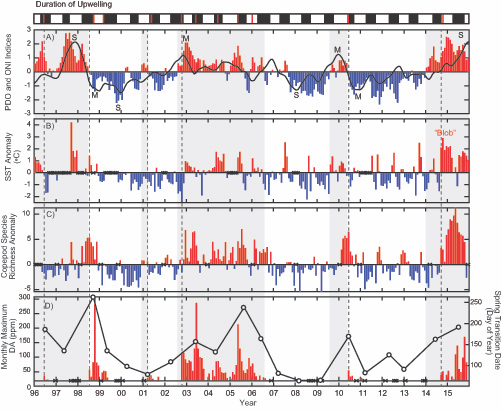

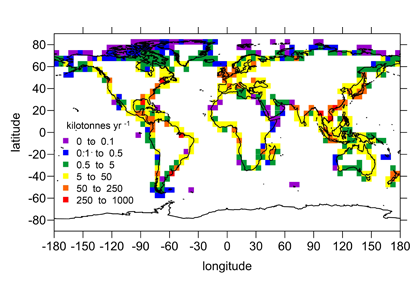

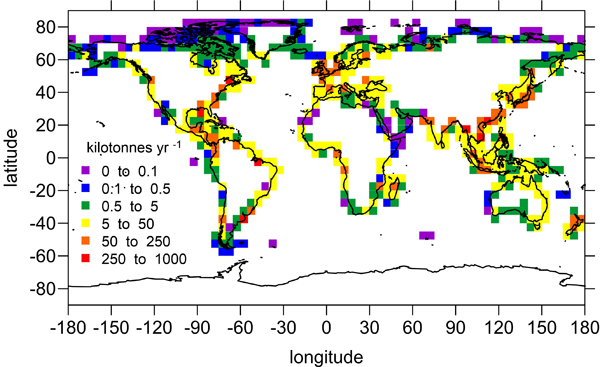

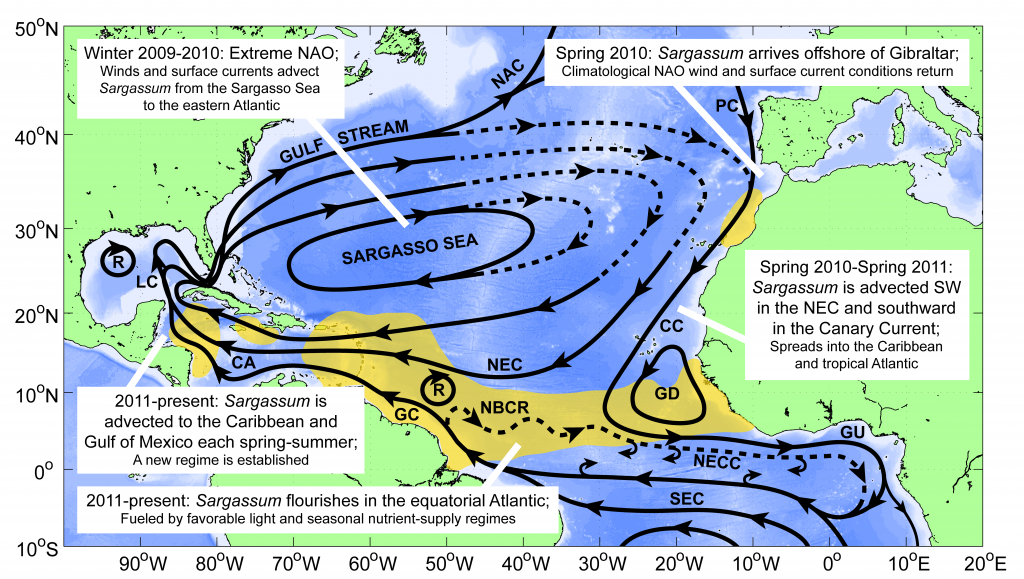

Figure 1. The hypothesized route of Sargasso Sea Sargassum to the tropical Atlantic and the Caribbean Sea. The solid black lines indicate the climatological surface flow, the dashed black lines indicate areas where there was variability from the average conditions.

The authors analyzed reams of satellite data and used computer models of the Earth’s winds and ocean currents to try to understand why these large mats started to arrive in coastal areas in 2011. A strengthening and southward shift of the westerlies in the winter of 2009-2010 caused ocean currents to move the Sargassum toward the Iberian Peninsula, then southward in the Canary Current along Africa, where it entered the tropics by the middle of 2010 (Figure 1). The tropical Atlantic provided ample sunlight, warmer sea temperatures, and nutrients for the algae to flourish. In 2011, Sargassum spread across the entire tropical Atlantic in a massive belt north of the Equator, along the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), and these blooms have appeared nearly every year since. Utilizing international oceanographic studies done in the Atlantic since the 1960s, and multiple satellite sensors combined with Sargassum distribution patterns, the authors discovered that the trade winds aggregate the Sargassum under the ITCZ and mix the water deep enough to bring new nutrients to the surface and sustain the bloom.

Improved understanding and predictive capacity of Sargassum bloom occurrence will help us better constrain and quantify its impacts on our ecosystems, which can inform management of valuable fisheries and protected species.

Authors:

Elizabeth Johns (NOAA AMOL)

Rick Lumpkin (NOAA AMOL)

Nathan Putman (LGL Ecological Research Associates)

Ryan Smith (NOAA AMOL)

Frank Muller-Karger (University of South Florida)

Digna Rueda-Roa (University of South Florida)

Chuanmin Hu (University of South Florida)

Mengqiu Wang (University of South Florida)

Maureen Brooks (University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science)

Lewis Gramer (NOAA AMOL and University of Miami)

Francisco Werner (NOAA Fisheries)