Climate change is expected to especially impact coastal zones, worsening deoxygenation in the Chesapeake Bay by reducing oxygen solubility and increasing remineralization rates of organic matter. However, simulated responses of this often fail to account for uncertainties embedded within the application of future climate scenarios.

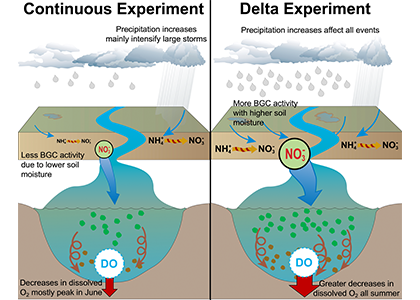

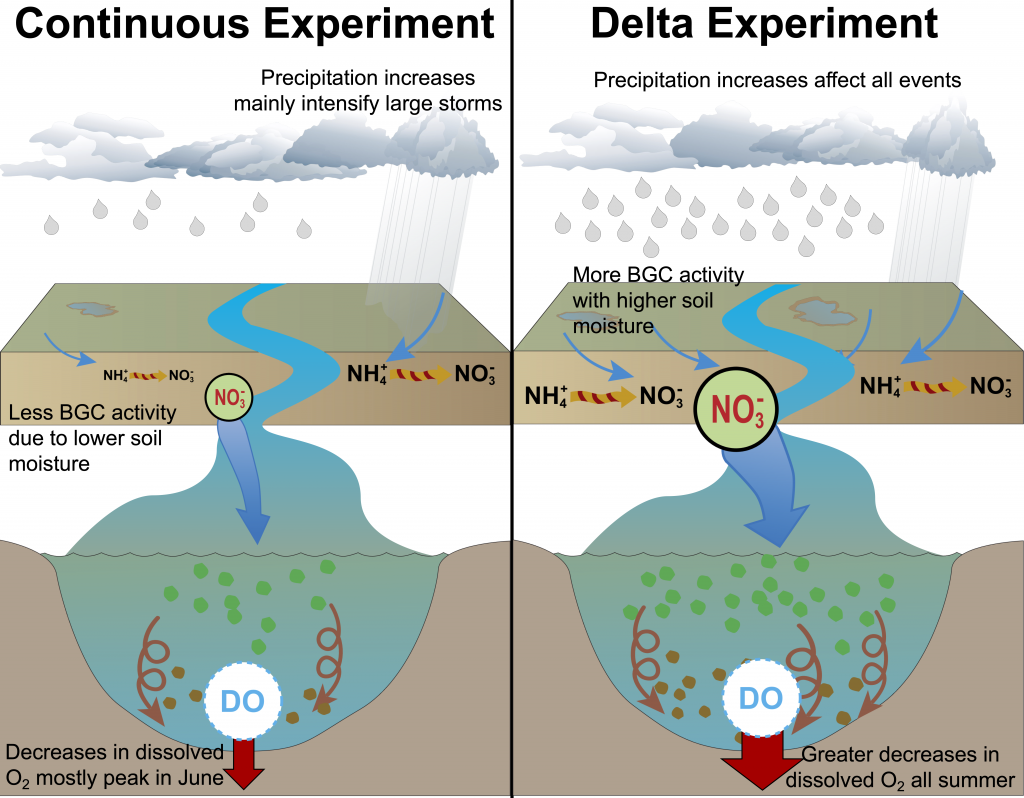

Recent research published in Biogeosciences and in Scientific Reports sought to tackle multiple sources of uncertainty in future impacts to dissolved oxygen levels by simulating multiple climate scenarios within the Chesapeake Bay region using a coupled hydrodynamic-biogeochemical model. In Hinson et al. (2023), researchers showed that a multitude of climate scenarios projected a slight increase in hypoxia levels due solely to watershed impacts, although the choice of global earth system model, downscaling methodology, and watershed model equally contributed to the relative uncertainty in future hypoxia estimates. In Hinson et al. (2024), researchers also found that the application of climate change scenario forcings itself can have an outsized impact on Chesapeake Bay hypoxia projections. Despite using the same inputs for a set of three experiments (continuous, time slice, and delta), the more commonly applied delta method projected an increase in levels of hypoxia nearly double that of the other experiments. The findings demonstrate the importance of ecosystem model memory, and fundamental limitations of the delta approach in capturing long-term changes to both the watershed and estuary. Together these multiple sources of uncertainty interact in unanticipated ways to alter estimates of future discharge and nutrient loadings to the coastal environment.

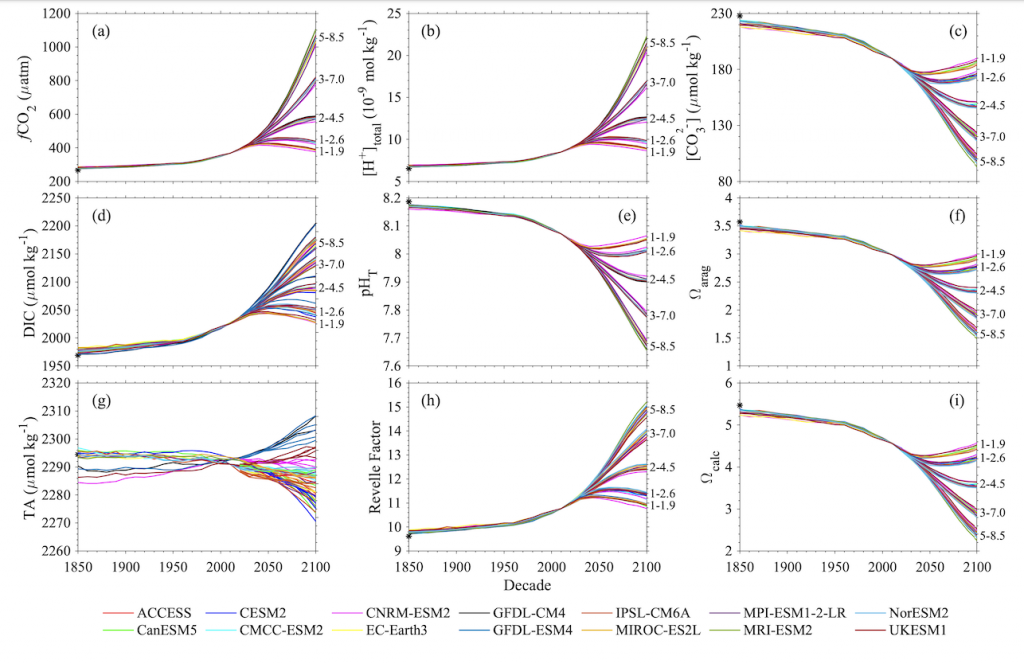

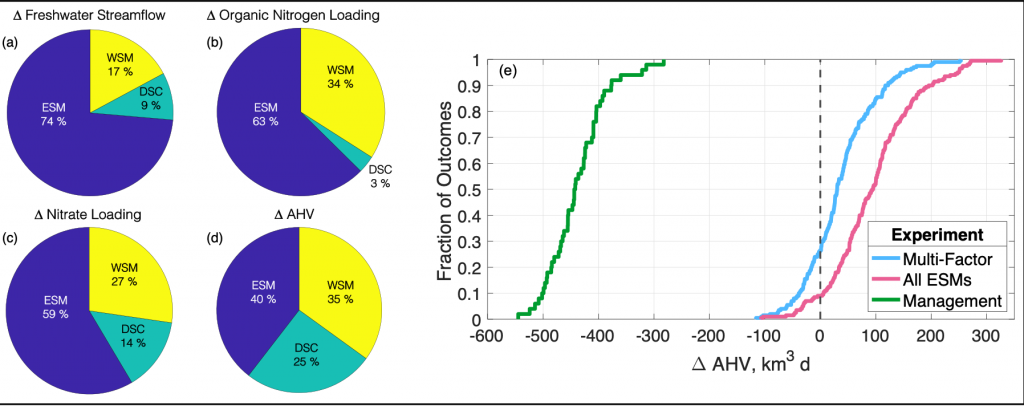

Figure 1: Chesapeake Bay hypoxia is sensitive to multiple sources of uncertainty related to the type of climate projection applied and the effect of management actions. Percent contribution to uncertainty from Earth System Model (ESM), downscaling methodology (DSC), and watershed model (WSM) for estimates of (a) freshwater streamflow, (b) organic nitrogen loading, (c) nitrate loading, and (d) change in annual hypoxic volume (ΔAHV). (e) Summary of all experiment results for ΔAHV, expressed as a cumulative distribution function. The Multi-Factor experiment (blue line) used a combination of multiple ESMs, DSCs, and WSMs, the All ESMs experiment (pink line) simulated 20 ESMs while holding the DSC and WSM constant, and the Management experiment (green line) only simulated 5 ESMs with a single DSC and WSM but incorporated reductions in nutrient inputs to the watershed. The vertical dashed black line marks no change in AHV.

Understanding the relative sources of uncertainty and impacts of environmental management actions can improve our confidence in mitigating negative climate impacts on coastal ecosystems. Better quantifying contributions of model uncertainty, that is often unaccounted for in projections, can constrain the range of outcomes and improve confidence in future simulations for environmental managers.

Figure 2: A schematic of differences between the Continuous and Delta experiments. In the Delta experiment a combination of altered distributions in future precipitation and changes to long-term soil nitrogen stores eventually result in increased levels of hypoxia (right panel).

Authors

Kyle E. Hinson (Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary)

Marjorie A. M. Friedrichs (Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary)

Raymond G. Najjar (The Pennsylvania State University)

Maria Herrmann (The Pennsylvania State University)

Zihao Bian (Auburn University)

Gopal Bhatt (The Pennsylvania State University, USEPA Chesapeake Bay Program Office)

Pierre St-Laurent (Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary)

Hanqin Tian (Boston College)

Gary Shenk (USGS Virginia/West Virginia Water Science Center)